Maghreb Noir: The Militant-Artists of North Africa and the Struggle

AUTHOR: Salah Chig

Book Reviews

Maghreb Noir:

The Militant-Artists of North Africa and the Struggle

Reviewed by Salah Chig

Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University

Paraska Tolan-Szkilnik. Maghreb Noir: The Militant-Artists of North Africa and the Struggle for a Pan-African, Postcolonial Future. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2023. xvi + 251 pp. Notes. Bibliography. Index. $30.00. Paper. ISBN: 978-1503635913.

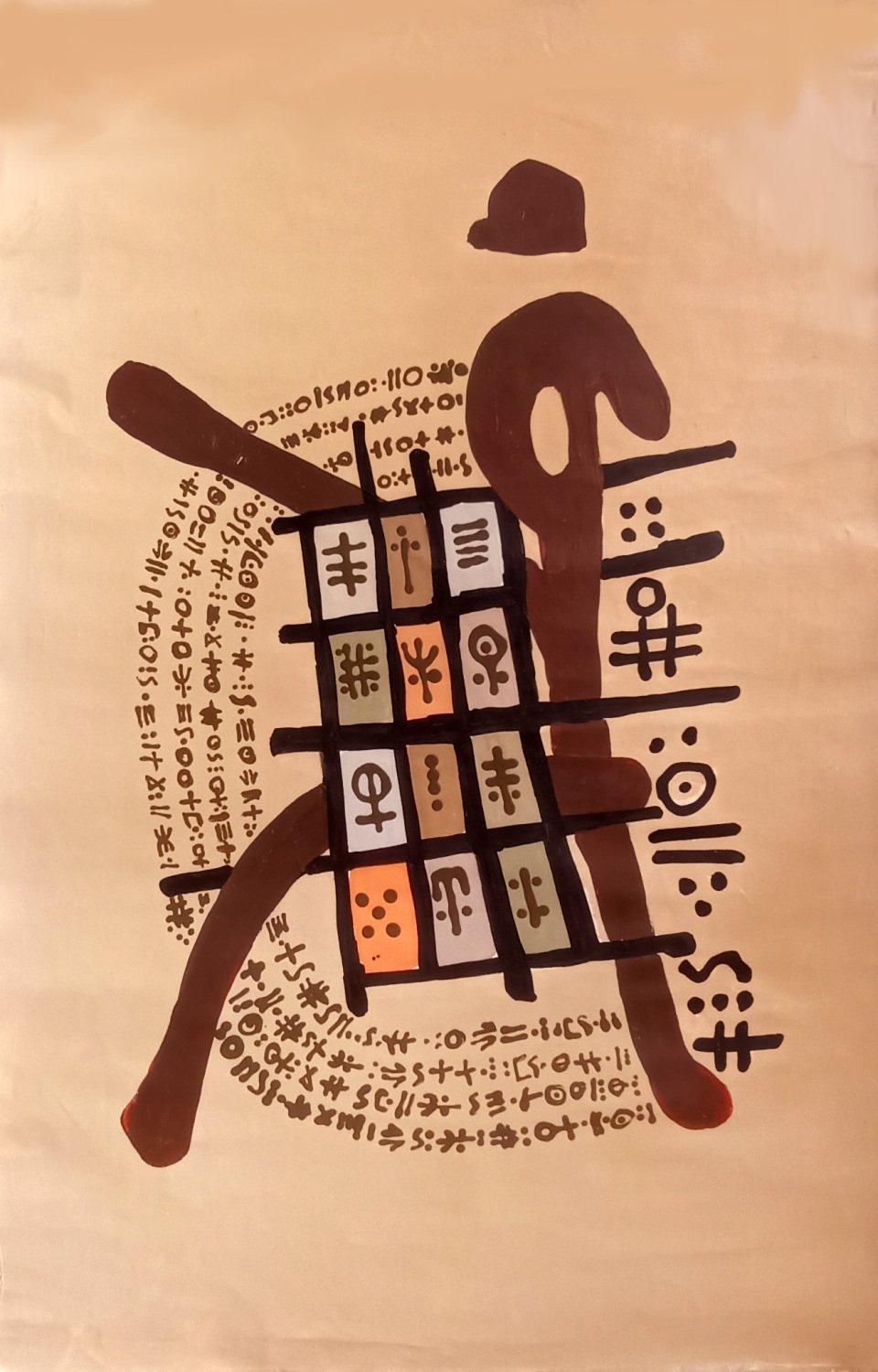

Maghreb Noir charts the role of North Africa as a locus of the Global South liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s. The book highlights the pivotal roles of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia as centers of revolutionary activity that attracted artists and freedom fighters from across the African continent, the Caribbean, and the Americas. Paraska Tolan-Szkilnik’s innovative conceptualization of “Maghreb Noir” expertly captures the complex dynamics of North-South convergence in Tamazgha, demonstrating how Mediterranean nations aligned themselves politically and culturally with sub-Saharan African independence movements. The study challenges the historical marginalization of North Africa in Pan-African narratives, reading against the imposition of the Sahara as a dividing line and proposing moving beyond this artificial separation. The author engages with recent scholarship on the dynamic exchange of people, goods, and ideas across the continent and beyond, including the transatlantic dimension as it is embodied in the experience of Black American intellectuals and artists, such as James Baldwin and Josephine Baker.

Across five chapters, the book traces the exchanges of revolutionary ideas and flourishing interactions through different media, including the literary journal Souffles, which featured poetry alongside theoretical and critical essays. It likewise addresses how the Algerian government extended hospitality to Black artists from America and the Caribbean, providing refuge from the white supremacist and racist environments of their home countries—a space that allowed them to engage with a diverse array of artists from various African nations via symposia, concert venues, cafes, and art galleries at a time when Algiers was called the “Mecca of revolutionaries.” Readers also learn of Tunisia welcoming a range of African artists, including filmmakers and poets, in turn facilitating their involvement in the state-sponsored film festival, Journées Cinématographiques de Carthage (JCC). The text frames the underlying incentives for Maghreb governments to endorse revolutionary artistic initiatives as being predominantly political rather than purely cultural or artistic.

Even though Tamazgha is the main focus of the book, Tolan-Szkilnik does not neglect the pivotal role Paris played in forming the Luso-African figures’ revolutionary mindset. It was there that Dos Santos, Andrade, and Bragança broadened their politico-literary education. Paris allowed them to be in contact with thinkers from around the world, including the Senegalese poet Léopold Sédar Senghor, the historian Cheikh Anta Diop, the Martinican poet Aimé Césaire, and the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, all of whom were abreast of the struggles of the European proletariat via their interactions with the French working class. Paris became increasingly unsafe and, inspired by Algerian War (1954-1962) and Moroccan independence, many Luso-African militants gradually reoriented to Africa, meeting in 1960 Tunis for the Second All-African People’s conference, establishing a permanent office in Rabat to liberate the Portuguese colonies, and organizing the Conference of the Nationalist Organizations of the Portuguese Colonies (CONCP) in 1961.

Maghreb Noir unpacks the historical and political environment leading to the emergence of the two cultural journals Lamalif and Souffles in Morocco—journals that facilitated communication and recruitment among leftist blocs. While Lamalif adopted a moderate, information-oriented approach, Souffles embraced radicality, directly confronting the government and engaging Luso-African poets and Pan-Africanist ideologies. The author attributes the revolutionary bent of Souffles to the editorial board’s encounters with intellectuals and militants from the Lusophone world including Mario de Andrade, Amílcar Cabral, Marcelino dos Santos, Agostinho Neto, and Aquino de Bragança. As the journal matured and its audience grew, an anticolonial journal publishing in a colonial language created an identity crisis for the editorial board. The journal dedicated two issues to Arabic-language poetry from the Maghreb and in 1971 Souffles’ editors decided to launch an Arabic-language offshoot, Anfas.

Tolan-Szkilnik foregrounds the political and ideological shift in 1960s Morocco that was taking place as King Hassan II oversaw a “retraditionalization” strategy that reinforced Morocco’s Arab identity and Islamic relations, aligning with Western powers during the Cold War and cutting ties with leftist movements. These and other political events urged Aquino de Bragança, Marcelino dos Santos, Mario de Andrade and others to relocate to Algiers. The monarchy intensified its authoritarian grip, banning leftist parties and employing violent repression against dissent, exemplified by the assassination in 1965 of prominent opposition figure Mehdi Ben Barka in Paris and a brutal crackdown on student protests that same year. The abuses of this period, which was known as the “Years of Lead,” included arbitrary detention and torture, which was documented by the Equity and Reconciliation Commission. As the center of the liberation movement moved to Algiers, personal and political connections between Moroccan activists and Luso-African militants persisted, as evidenced by continued travel and collaboration across cultural and intellectual networks.

The Pan-African Festival of Algiers (PANAF) in 1969 earned the city the name “Mecca of Revolutionaries.” Representatives from forty African countries and radicals worldwide met in the city throughout the time of the festival to strategize against colonialism. Differing opinions on the utility of festivals led to factionalism early on as some intellectuals argued the festival was a waste of time and did nothing to alleviate the situation of the Algerian youth. Moreover, many “Maghreb Generation” members saw the PANAF as a façade that hid the decline of revolutionary ideals in Algeria and in Africa. These artists and intellectuals maintained independent cultural spaces in cafés and at private gatherings.

Moreover, while the Algerian government and male participants celebrated the festival as a triumph of Pan-African unity and cultural exchange, women’s experiences, particularly those of Black Panther members like Kathleen Cleaver, tell a story of isolation, exclusion, and objectification. The book exposes how in spite of progressive aims, revolutionary spaces often perpetuated existing power structures, with women relegated to supporting roles as men dominated political discourse. Male interviewees’ memories focused on sexual liberation and women’s bodies rather than substantive political participation. Furthermore, official narratives glossed over cultural tensions and racial complexities, such as North Africans' reluctance to identify as African. The author shows that this disconnect between public celebration and private experience underscores how revolutionary movements can simultaneously challenge some forms of oppression while reinforcing others, particularly gender-based exclusion.

Within the Tunisian context, Tolan-Szkilnik introduces Tahar Cheriaa, the “father of Tunisian and African cinema” and founder of the Journées Cinématographiques de Carthage (JCC). This film festival, which was launched in 1966, aimed to challenge the dominance of Hollywood and soon became a platform for Pan-African cinema and dissent, operating with relative autonomy from the government. The festival became increasingly politicized up through the late 1960s, alongside growing student resistance to Bourguiba’s regime. The Pan-African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI) emerged from the JCC in 1970, uniting filmmakers across linguistic zones in its mission to combat Western film distribution companies and promote the nationalization of cinema. The 1975 Algiers Charter defined African filmmakers as “creative artisans” in the service of their people, emphasizing revolutionary and educational content over commercial success. FEPACI achieved early successes and substantial political influence, with several African nations nationalizing their film industries. A consequence of these successes, however, meant the federation soon faced growing challenges from Western distribution companies and African governments. By 1982, the organization had shifted its anti-Western stance and returned to working with European companies. Similarly, the JCC festival became progressively commercialized by the late 1970s, with growing influence from Egyptian stars and commercial interests.

Throughout the pages of Maghreb Noir, Tolan-Szkilnik reconstructs the intricate dynamics of the Maghreb Generation’s movements, friendships, intimate relationships, and artistic output by meticulously examining traditional and non-traditional archives across five languages. The author deftly draws on a diverse range of primary sources, including but not limited to personal papers, interviews, and multilingual archival materials. While acknowledging the challenges of accessing state archives in the Maghreb, Tolan-Szkilnik explains her strategic reliance on alternative sources, including French diplomatic archives, personal collections, and interviews. She elaborates on her own positionality in interviews and unexpected insights within the text, especially regarding sexual liberation and marginalization. As a result of these novel choices, the author expresses an urgent concern for documenting this history as its protagonists enter later stages in life, with many materials and firsthand accounts at risk of being permanently lost. The author frames her work not as a definitive history but as an invitation for further research and discovery of hidden archives that can expand our understanding of Pan-African movements across the Maghreb, stressing that many archives are to be found in attics, basements, and memories.

The work accentuates the importance of decentering European perspectives in understanding African cultural movements, highlighting the inextricable links between art and political activism in the Maghreb Generation. By mingling micro- and macro-historical perspectives, this work argues for a redefined understanding of Maghreb history that encompasses the entire African continent, positioning the region as a vital center of intellectual and cultural production during the latter half of the twentieth century. The book critically assesses modern North African governments’ selective reclamation and sanitization of this revolutionary past for contemporary political purposes. This text is essential for grasping the significance of a range of media, including film and art festivals, literary journals, and more in fostering and disseminating ideas that challenge racism, imperialism, and colonialism. Maghreb Noir is a crucial resource for anyone seeking to comprehend the participation and influence of Maghreb nations in African independence movements, alongside the impact of revolutionary artists within broader anti-imperial efforts throughout the Global South.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 3 • Issue 1 • Spring 2025

Pages 111-115

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University