Sounds of Identity and Resistance: A Journey Through Amazigh Music

AUTHOR: Airy Dominguez

Scholarly Translations

Sounds of Identity and Resistance: A Journey Through Amazigh Music

Airy Dominguez

Universidad de Salamanca

Abstract: For generations, Amazigh music has served as a vital space for cultural articulation, resistance, and transnational dialogue. Rooted in oral tradition, it has preserved and transmitted Amazigh identity across time. Initially dismissed as folklore, its significance was diminished by colonial and post-colonial narratives. However, it has proven a powerful vehicle for political and cultural expression, challenging marginalization from the colonial era and particularly since the 1970s, amid a broader cultural and linguistic resurgence. From oral poetic traditions to the rise of musical activism and the global reach of Tuareg desert blues, Amazigh music has adapted to political and social transformations while maintaining its linguistic and cultural essence. Today, generations of musicians in Tamazgha and the diaspora blend ancestral sounds with contemporary influences. This article examines the evolution of Amazigh music as a sonic space where indigeneity is affirmed, heritage reimagined, and identity expressions transcend territorial and temporal boundaries.

Keywords: Amazigh music, Amazigh identity, cultural identity, desert blues, tamazgha.

The Imazighen are the indigenous people of the broader North Africa also known as Tamazgha. United by a shared language (Tamazight), Imazighen have made oral tradition one of the cornerstones of their resistance. This orality has been crucial in their survival throughout centuries of invasions. The Phoenicians, the Romans, the Byzantines, and the Arabs invaded the Imazighen centuries ago and more recently, the French and Spanish colonial Powers colonized them. Within this historical context, music has played a pivotal role as a medium of expression and cultural transmission in Amazigh societies. It has served as a sanctuary for preserving the language, history, culture, and identity of these Indigenous people who have shown a phenomenal resistance.

Amazigh (singular of Imazighen) music embodies a chameleon-like form of expression, constantly adapting to the ticking clock of time—evolving from traditional oral poetry to a contemporary explosion of bands and emergence of artists who skillfully blend the ancestral musical tradition with the modern melodies and instruments. This evolution has elevated Amazigh language, demands, and culture to greater prominence on the international stage.

Photo courtesy of the musical group Meteor Airlines. Taken in London during the band's UK tour, May 2024.

The Oral Tradition: The Heart of Amazigh Cultural Preservation

The Imazighen possess one of the oldest writing systems in North Africa: Tifinagh. However, it is not tied to an extensive literary canon in written form, unlike their rich oral literary tradition. As Brahim El Guabli explains in his article “Translation and Rehabilitation: An Introduction to Indigenous Amazigh Literary Output” (El Guabli 2024), this is partly due to literary dynamics that have pushed Indigenous writers to favor languages with greater social prestige, such as Latin, Arabic, French, or Spanish. Within this context, colonial scholars categorized Amazigh literature solely as oral, diminishing its significance and, at times, denying its existence altogether—an approach that later influenced Arab nationalist discourse and post-independence cultural policies.

For centuries, memory has been the cornerstone of the Imazighen’s cultural preservation. Stories, myths, songs, proverbs, poetry, and narratives have formed the foundation for transmitting and safeguarding their identity. Through the spoken word, the history of their communities—along with their values and beliefs—has been passed down from generation to generation, shaping their collective memory. As Mohamed Oubenal highlights in his article “Les défis de la musique urbaine amazighe: Le cas des artistes d’Agadir” (Oubenal 2020:105), Amazigh oral tradition thus acts as a bridge between the past and the present, offering a temporal journey that has, in recent decades, inspired numerous artists (singers, musicians, painters, and others) to reconnect with their roots in search of inspiration. In this journey from the past to the present, contemporary technologies play a pivotal role, providing new opportunities for the dissemination, preservation, and expansion of Amazigh identity. Hence, Amazigh music serves as a connector between generations of artists who each sustain the tradition while also transforming it.

Almost paradoxically, modern times offer a stage for the past, creating a space where ancient oral tradition blends seamlessly with the present and reaches the international stage. This trajectory, particularly in the realm of music, began to take root in various North African and Sahelian countries during the 1970s.

The 1970s in Algeria and Morocco: A Springboard to Internationalization

For decades, Amazighness and its musical expressions were relegated to the realm of folklore, perpetuating the exoticism rooted in the colonial imagery, which was transmitted to nationalist elites in the post-independence period. This marginalization and distortion of reality persisted, despite documented evidence of their role as a form of resistance during the colonial era. In Morocco, for instance, the legendary Amazigh singer Hammū al-Yazīd—mentor to Mohamed Rouicha—left a significant mark as early as the 1960s; a legacy that scholar Mounia Mnouer has discussed in her article “The Amazigh Musical Style of Rouicha: Transcending Linguistic and Cultural Boundaries” (Mnouer 2022).

Despite these early roots, the cultural resurgence of Amazigh identity truly emerged in the 1970s and was closely tied to a broader political awakening among the Amazigh youth. During this period, demands for the recognition of Amazigh language and culture gained momentum in countries like Algeria and Morocco, creating the ideal environment for the rise of influential Amazigh musicians who also paved the way for international recognition. This musical renaissance was further fueled by the urbanization processes initiated in the previous decade and which enabled musical expressions to move beyond community spheres and reach urban centers (Oubenal 2020:101). The encounter with the urban environments adapted and reshaped the evolution of this music.

The 1970s Morocco presents several examples of this cultural revival. One prominent example is the group Izenzaren, which became synonymous with tazenzart (“the Izenzaren style” or “the musical style of the rays of the sun”). This style resonated deeply with Amazigh youth, satisfying their thirst for modern and rebellious music. As El Guabli highlights in his article “Musicalizing Indigeneity: Tazenzart as a Locus for Amazigh Indigenous Consciousness” (El Guabli 2024b), Izenzaren introduced two major innovations that set them apart from classical Amazigh songs, such as those by Lhaj Belaï, which often exalted powerful figures or focused on themes of religion and wisdom. The first innovation was the adaptation of poetry into music, reflecting the introspective work of Amazigh poets who sought to assert their place in a world that had marginalized their language. The second was the incorporation of new instruments, such as the banjo, violin, and tam-tam, into Amazigh music. These additions broke away from the monotony of traditional instruments like the ribāb (a type of fiddle) and nnaqūs (a metal cowbell), introducing fresh sounds and rhythms. For example, Iggout Abdelhadi, Izenzaren’s lead banjo player, probably influenced by watching Indian cinema, brought Indian and Tibetan melodies into Amazigh music, further enriching its repertoire.

A few years later, another wave of artists emerged, including the musical group Usman, thanks to the work of AMREC (Association Marocaine de Recherche et d'Echange Culturel) (Oubenal 2020:101). Composed of young Imazighen based in Rabat, Usman incorporated the guitar, performed poetic lyrics, and blended Western melodies, drawing on the modern musical training of some of its members. Their lead singer, Ammouri, grew up in a Franciscan orphanage in Taroudant, which played a key role in his development as a trilingual musician. This resurgence brought a breath of fresh and transformative air to the urban Amazigh music scene in Morocco, particularly in the Rabat-Casablanca area (El Guabli 2024b). Similarly, the legend of Mohammed Rouicha was also born in the 1980s (Mnouer 2023). A disciple of the renowned Hammū al-Yazīd, Rouicha, who sang in both Tamazight and Darija, left an indelible mark on Amazigh music.

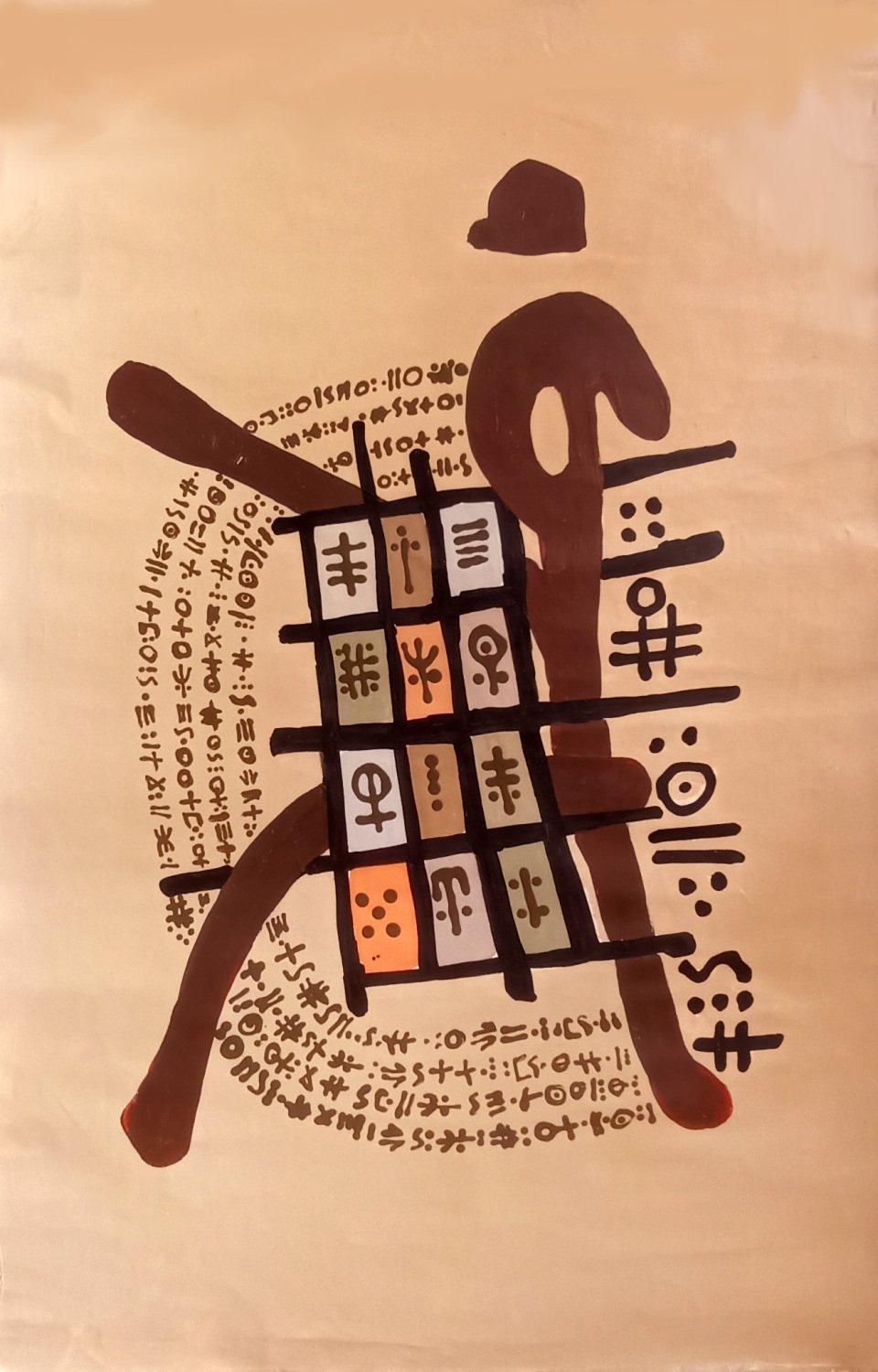

In Morocco, the evolution from traditional Amazigh music—characterized by its long poetic compositions accompanied by rhythmic instruments such as the bendir and drum, often performed in styles like Ahwach, Ahidous, Regda, and Rekza—to modern Moroccan Amazigh music has been further elaborated by visual artist, singer, and composer Moha Mallal. A multifaceted artist, Mallal has actively contributed to the transformation of Amazigh music. His insights can be found in the interview titled “The Music, Voice of the Amazigh Soul and Its Future Challenges” (Anglade 2024), where, among other aspects, he highlights that Amazigh artistic expression arises from a need for recognition and cultural preservation. Amazigh artists, he argues, continue to focus on their identity, language, and traditions because they feel their culture is not sufficiently respected in their own country. He also describes the evolution of Amazigh music, distinguishing between traditional and modern music, and introduces the concept of Amun Style, a unique musical identity from southeastern Morocco that blends traditional elements with contemporary sounds while maintaining a strong connection to its territory. Furthermore, he reflects on the role of Amazigh music as both a space of memory and cultural celebration, while also denouncing the marginalization it continues to face in contrast to Arabic or foreign music in festivals and cultural platforms.

This musical revival and reinvention happened simultaneously in Morocco and Algeria. As these developments were unfolding in Morocco, Idir emerged as one of the most influential figures in the history of Amazigh music in Algeria. His 1973 song “A Vava Inouva” became an anthem, resonating deeply not only with the Kabyle people (an Amazigh group from northern Algeria) but also on a regional and international scale. “A Vava Inouva” has created a memory of its own and is one the most efficient carriers of Amazigh consciousness in the musical genre.

Idir holding the Amazigh flag at one of his concerts. Source.Le360.

In “A Vava Inouva”, the oral tradition that defines the Amazigh people is vividly embodied. The song, an adaptation of an oral legend, narrates the story of a mother singing to her child on a cold night. Through this work, Idir bridges the past and the present, both acoustically and thematically. It serves as a call to preserve Amazigh identity, showcasing the power of oral transmission, countering the folklorization of Amazigh culture, and fostering a sense of belonging for Imazighen around the world. By 1978, the song had sold approximately 200,000 copies (Goodman 2020), cementing its place as a cultural anthem.

Idir, along with other artists like Aït Menguellet, Matoub Lounès, Khalid Izri, and bands such as Djurdjura and Izenzaren, moved beyond the orchestrations popularized in the 1940s under the influence of Andalusian and Egyptian music. They ushered in a new era where Amazigh youth became increasingly aware of their subaltern status. Music emerged as the umbilical cord connecting them to their roots, both in their home countries and within the diaspora. It became a powerful vehicle for raising Amazigh consciousness and a platform for defending their indigenous language and culture, transcending geographical borders.

Desert Blues: the Tuareg resistance

Barely a decade later, in the vast expanse of the Sahara, the Tuaregs—part of the Amazigh population—began to make their instruments and vocal cords resonate. In the 1980s and 1990s, some young Malians, who had come close to taking up arms against the discriminatory policies of the government in Bamako, found in music a powerful means of expressing their identity and their dream of an aborted postcolonial Tuareg nation. In the absence of the physical nation, low-quality cassette recordings circulated across exile territories, carrying the voices of artists such as Brahim Ag Alhabib and Abdallah Ag Alhousseini. These artists, who journeyed to Libya and Algeria during the 1980s, would later give rise to the renowned band Tinariwen.

Cover of Kel Tinariwen, originally released in 1991 and reissued in 2022.

The songs of Tinariwen quickly became a powerful tool for communication and raising awareness, reaching audiences far beyond their desert homeland. Through their music, the Amazigh nomadic peoples of the Sahara found a voice in the genre known as “desert blues,” which blends traditional Tuareg poetry with rhythms and melodies influenced by rock and blues.

The members of Tinariwen, which means deserts, play instruments such as the teherdent (lute), imzad (violin), tinde (drum), and electric guitar, creating a distinctive musical fusion. Their sound blends the Tuareg assouf style—meaning “loneliness” or “nostalgia”—with influences from contemporary Kabyle Amazigh songs (e.g., those of Idir and Aït Menguellet), Malian blues, Algerian urban raï, Moroccan chaabi, pop, rock, and even elements of Indian music, as journalist and researcher Andy Morgan highlights in one of his articles.

Andy Morgan, “Tinariwen – Sons of the Desert.” Andy Morgan Writes, February 2007.

In Tinariwen’s lyrics, history and identity resonate deeply. Nostalgic notes of exile, struggles for self-determination, and hopes for a brighter future for the Tuareg people are ever-present. The “rebellion” against the oppression of the Malian state emerges as a recurring motif, offering a critique of the repression of Tuareg uprisings, particularly during the 1960s (Merolla 2020:38), when France exploited the racial tensions between the Tuaregs and the leaders Afro-leaders of the nascent Malian army to dispossess the Tuaregs. Alongside these verses of longing and resistance, contemporary grievances also find a voice. The lyrics reverberate as a collective lament, a murmured expression of dreams and experiences that transcend borders and generations.

Once again, voices and instruments build a bridge between the present and the past, creating a connection that transcends seas and borders while giving visibility to, preserving, and promoting Amazigh identity. Alongside this continuity, Tinariwen introduced a groundbreaking element that would resonate with future generations of artists: the importance of visual storytelling and stage presence.

By redefining the image of the Tuaregs beyond the colonial fantasies of great warriors, the band incorporates powerful imagery—4x4 vehicles, camels, and elegantly dressed men wearing veils and turbans. These visual elements quickly captivated international audiences. In 2005, their album Amassakoul (“The Traveler”) sold over 100,000 copies, and in 2012, they won the Grammy Award for Best World Music Album in Los Angeles. Tinariwen is now a fixture of international music festivals across the globe.

Photo courtesy of the musical group Tarwa n-Tiniri. The image highlights the influence of the aesthetic shift introduced by Tinariwen decades ago, which now permeates a wide variety of Amazigh singers and bands.

Photo courtesy of scholar Hamza Amarouch.

Also in the Sahelian lands, during the 1980s, Omar Moctar—known as Bombino—was born in the Tuareg nomadic camp of Tiden, about 80 kilometers northeast of Agadez (Niger). Through his music, Bombino has given voice to the identity and history of his people, becoming a symbol of a new Tuareg generation.

Like the members of Tinariwen, the turbulent political context of his homeland forced Bombino into exile multiple times, leading him to settle in countries such as Algeria, Libya, and Burkina Faso. A fervent advocate for the teaching of Tamasheq (the Tuareg language) and deeply committed to promoting equal rights, peace, and cultural preservation, Bombino channels his convictions through his music. His sound, born from the heart of the Sahara and the Sahel, fuses traditional Amazigh rhythms with the electrifying energy of rock and roll. After years of drought, rebellion, and oppression, Bombino’s music not only preserves the memory of who the Tuareg are but also inspires a vision of who they can become.

From the Sahel, the southern part of Tamazgha, other voices have also gained international recognition, such as that of Tuareg guitarist and songwriter Mdou Moctar whose lyrics explore themes of love, religion, women’s rights, inequality, and the exploitation of West Africa by colonial powers. Together with artists like Bombino, Mdou Moctar represents a powerful wave of Tuareg musicians, who use their art not only to preserve their cultural heritage but also to shed light on pressing social and political issues, ensuring that the voices of Tamazgha, combining both the Sahara and the Sahel, resonate far beyond their borders.

The New Generations: Continuity, Global Expansion, and Voices of the Diaspora

Following in the footsteps of their predecessors, younger generations have embraced music as a powerful tool for cultural and political expression. Inspired by the past, they have adapted to modern times by blending traditional elements with contemporary sounds and styles, all while expanding their presence on the international stage.

Photo courtesy of the musical group Meteor Airlines, provided to the author. It was taken in Tiznit, Morocco, during the American Music Abroad program in May 2024.

An essential part of the Amazigh musical landscape of the younger generations is found in Morocco. Among the standout artists is Saghru Band, which gained prominence by blending rock with traditional Amazigh elements within the context of Amazigh achievements within the country. The establishment of the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture (IRCAM) in 2001 and the recognition of Tamazight as a constitutional language in 2011 have had a tremendous impact on Amazigh music, which, like Saghru Band, addresses themes of cultural oppression, injustice, and the struggle for Amazigh rights. Their songs have served as a call to mobilization and defense of the Imazighen while also acting as a bridge between generations.

Adopting a more innovative approach, groups like Meteor Airlines have emerged, drawing on influences from pop, electronic music, and urban genres. With their eclectic style, Meteor Airlines appeals to a younger audience seeking an Amazigh identity that embraces modernity while remaining firmly rooted in tradition. Ikbale Bouziane, in her article entitled “Engaged Amazigh Poetry in Meteor Airlines' 'Agdal': Reviving Tradition while Addressing Global Environmental Issues,” has analyzed the band’s 2024 album Agdal (Bouziane 2024), which revitalizes traditional Amazigh poetry while tackling contemporary global environmental challenges.

This blend of past and present is also evident in their stage presence. During public appearances, concerts, interviews, and promotional activities, the band often dons traditional attire such as the Azennar or burnous. According to the group, wearing the Azennar symbolizes the spirit of unity and collective leadership, while simultaneously paying homage to their traditions and cultural heritage.

Photo provided by the musical group Meteor Airlines to the author.

Another musical group making waves on the national stage and gaining international recognition is Tarwan-Tiniri (“The Children of the Desert”). Their compositions effortlessly blend traditional Amazigh sounds with jazz, reggae, and desert blues, while the desert's aesthetics remain a central and defining element of their artistic identity.

Photo provided by the musical group Tarwa n-Tiniri to the author of the article.

These are just some of the bands that enrich the vibrant Amazigh music scene in Morocco. The landscape also features singer-songwriters like Muha Mellal and Imran Azrou, as well as locally renowned groups such as Tagrawla, recognized for their activist character and commitment to the social and cultural causes of the Imazighen. Alongside them are artists like Kawtar Sadik, who performs rock and rap in Arabic and Tamazight with fusion compositions; Jubantouja, who merges alternative indie rock with Amazigh heritage; and Sarah and Ismael, a musical duo creating soul, jazz, and rhythms of Tamazgha (the Amazigh homeland) in a creative journey spanning from Shanghai to Morocco.

In Algeria, voices like Ali Amran and popular groups such as Taous Athan, Nouria, and Celia are part of the Amazigh music scene. While many of their performances take place within the country—primarily in Kabylie—they are frequently invited by the diaspora to perform in countries such as Canada and France.

In the Sahel, artists from diverse backgrounds (including Mali, Niger, Algeria, and France) come together in groups like Tamikrest, whose name in Tamasheq means “knot, coalition, connection”. Inspired by the legacy of Tinariwen, Tamikrest continues to carry the torch of artists like Ali Farka Touré—a musician and farmer who pioneered a unique style rooted in ancient traditions and connected to rural American blues, giving rise to the term “desert blues”.

In this new era, Amazigh artists are thriving, with growing visibility both locally and internationally. The diaspora plays a crucial role in this resurgence, acting as both a producer and a receiver of Amazigh art. Among these emerging voices is NaYra, who uses her music to reconcile her cultural heritage with life in a globalized world. Her style blends contemporary pop influences with Amazigh rhythms, creating a fresh sound that captures the experiences of young Amazigh individuals in the diaspora.

Another prominent figure is Hindi Zahra, who sings in English and Tashlḥīyt, seamlessly fusing Chleuh sounds with blues, jazz, American folk, Egyptian music, and the influences of other African artists such as Ali Farka Touré and Youssou N'Dour.

Language and Struggle: A Pattern That Crosses and Blurs Borders

From the Atlas Mountains to the Sahara Desert and the global cities where the Amazigh diaspora resides, Amazigh music emerges as a universal language that bridges the past, present, and future. Thematically, a significant portion of Amazigh songs can be categorized as “protest music”. Many lyrics carry political undertones, reflecting the historical struggles of the Amazigh people to live and express themselves freely in their own language. The question of identity remains a persistent theme, inspiring artistic inquiries such as: Who are we? Why are we oppressed? Who is responsible for these oppressive conditions? Alongside these political themes, topics like love, philosophy, and societal issues also feature prominently.

For women, the construction of contemporary Amazigh identities through music often incorporates a distinctly gendered dimension. Female artists frequently reflect on life from their marginalized position in relation to men, challenging traditional gender roles and norms of femininity within their communities.

Notable figures in this sphere include Hindi Zahra, Nouara, Cherifa, Tabaaramte, and Djurdjura. As Daniella Merolla further elaborates in her article “Amazigh/Berber Literature and “Literary Space.” A contested minority situation in (North) African literatures,” these artists navigate and negotiate the intersections of identity, gender, and culture through their work (Merolla 2020:38-39).

In terms of form, Amazigh artists often draw on their native tongues—either independently or in combination with others—while incorporating musical elements rooted in their cultural traditions. This approach allows them to distinguish themselves on the international stage, all while resisting the dominance of hegemonic languages and political systems. Amazigh music thus becomes a dynamic space that not only preserves identity but also bridges the past and present, fosters innovation, and transcends both physical and imaginary borders.

Through their music, the Imazighen have entered the global public sphere, consolidating a shared identity that, despite its internal diversity, has withstood repeated attempts at cultural assimilation and survived policies of oppression and marginalization. This music has also built a bridge between the voices and minds of Tamazgha and its diaspora. Idir’s frequent visits to Morocco and his well-known friendships with Amazigh activists exemplify this connection. More recently, connections such as the one between Saghru Band with Algerian singer Oulahlou highlight how this cultural network continues to expand, uniting generations in a shared legacy that transcends both time and borders. Music is one of the areas in which Tamazgha is not just an aspiration but a lived, sonic reality.

Photo courtesy of the musical group Meteor Airlines. The image shows the group from behind, wearing azennar or burnous.

References

Anglade, Eric. “The Music, Voice of the Amazigh Soul and Its Future Challenges.” Southeast Morocco, May 17, 2024. https://southeast-morocco.com/the-music-voice-of-the-amazigh-soul-and-its-future-challenges

Bouziane, Ikbale. 2024. “Engaged Amazigh Poetry in Meteor Airlines' Agdal: Reviving Tradition while Addressing Global Environmental Issues.” Journal of Gender, Culture and Society 4(2):119–125.

El Guabli, Brahim. 2024b. “Musicalizing Indigeneity: Tazenzart as a Locus for Amazigh Indigenous Consciousness.” Tamazgha Studies Journal 2(1):26–45.

El Guabli, Brahim. 2024a. “Translation and Rehabilitation: An Introduction to Indigenous Amazigh Literary Output.” Words Without Borders, November 19, 2024. https://wordswithoutborders.org/read/article/2024-11/translation-and-rehabilitation-an-introduction-to-indigenous-amazigh-literary-output-brahim-el-guabli

Goodman, Jane E. 2020. “Idir: How a Song from the Village Took Algerian Music to the World.” The Conversation, July 6. https://theconversation.com/idir-how-a-song-from-the-village-took-algerian-music-to-the-world-141418

Merolla, Daniela. 2020. “Amazigh/Berber Literature and ‘Literary Space’: A Contested Minority Situation in (North) African Literatures.” In Routledge Handbook of Minority Discourses in African Literature, ed. Tanure Ojade and Joyce Ashuntantang, 27-47. London: Routledge.

Mnouer, Mounia. 2022. “The Amazigh Musical Style of Rouicha: Transcending Linguistic and Cultural Boundaries.” Review of Middle East Studies 56(2):264–276.

Oubenal, Mohamed. 2020. “Les défis de la musique urbaine amazighe: le cas des artistes d’Agadir.” In Expressions musicales amazighes en mutation, El Khatir Aboulkacem, Hammou Belghazi, Mohamed Oubenal and Mbark Wanaim, 101-124. Rabat: Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe.

Translated from the Spanish original by the author.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 3 • Issue 1 • Spring 2025

Pages 83-94

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Universidad de Salamanca