A Geocontourglyph for Gypsum in Sidi Jafaar

AUTHOR: Abdellah El Haloui

New Directions

A Geocontourglyph for Gypsum in Sidi Jafaar

Abdellah El Haloui

Cadi Ayyad University

Abstract: In this paper, an ancient Amazigh inscription consisting of the single word “agabs” discovered on a rock in Sidi Jaafar, Morocco is examined. The rock itself is analyzed as a geocontourglyph—a deliberate marking by which travelers were guided to gypsum deposits in the region. Phonological and semantic connections between the inscription and the modern Moroccan Arabic term “gəbs̃” (gypsum/plaster) are established through rigorous linguistic analysis of the Touareg Tifinagh script and comparative study across Afro-Asiatic and Indo-European language families. The historical continuity of terminology and mineral exploitation in North African cultures is shown, with geological evidence being provided to confirm gypsum abundance in the area. Potential etymological origins of the word “gypsum” are revealed, with early meanings of “mature,” “ripen,” or “mold” being suggested. Insight into resource mapping practices and linguistic exchange in North Africa is provided by this discovery.

Keywords: Amazigh linguistics, geocontourglyph, Tifinagh script, gypsum mineral, Afro-Asiatic etymology.

Introduction

The objective of this paper is to interpret the meaning of an old Amazigh (Berber) [1] inscription, arguably a word that could be pronounced as /agabs/, /aggabs/, or /agabbəs/, which is pecked on the upper surface of a rock in Sidi Jaafar, a village located in the community of Toundout, Ourazazate Province, Morocco. Even though Amazigh speakers no longer use this word in their modern dialects of Amazigh, I argue that it probably means “gypsum” or “plaster.” My argument for this interpretation is based on a linguistic analysis of the word, an exploration of its possible cognates in Afro-Asiatic and Indo-European language families, and an interpretation of the function of the Sidi Jaafar rock as a geocontourglyph used more than 1200 years ago to guide local tribesmen to a “gypsum” mineral site. This paper will shed light on a probable ancestral meaning of the word gypsum as “mature,” “ripen,” or “mold.”

The site of the SJ Rock

The word I want to interpret in this article is pecked on a rock that measures 25 cm high and 65 cm wide and that is deposited at a location with coordinates of 31,237710 latitude, -6,539402 longitude. This rock is deposited near Sidi Jaafar, a village located in the community of Tounoudt, Ourazazat Province, Draa Tafilalt Region, Morocco. In this paper, I refer to this rock as S(idi) J(aafar) rock.

The SJ rock is of the sandstone type. The reddish color on its fresh fracture is due to oxidation, since the rock is deposited in a continental environment where oxygen oxidizes the iron contained in the rock. The blackish color on the patina is due to a prolonged period of exposure to solar radiation. Two hypotheses can explain the current location of the rock: i) the rock was pecked on site after it had been transported to its current location; ii) the rock had been first pecked elsewhere and was subsequently transported to the current location.

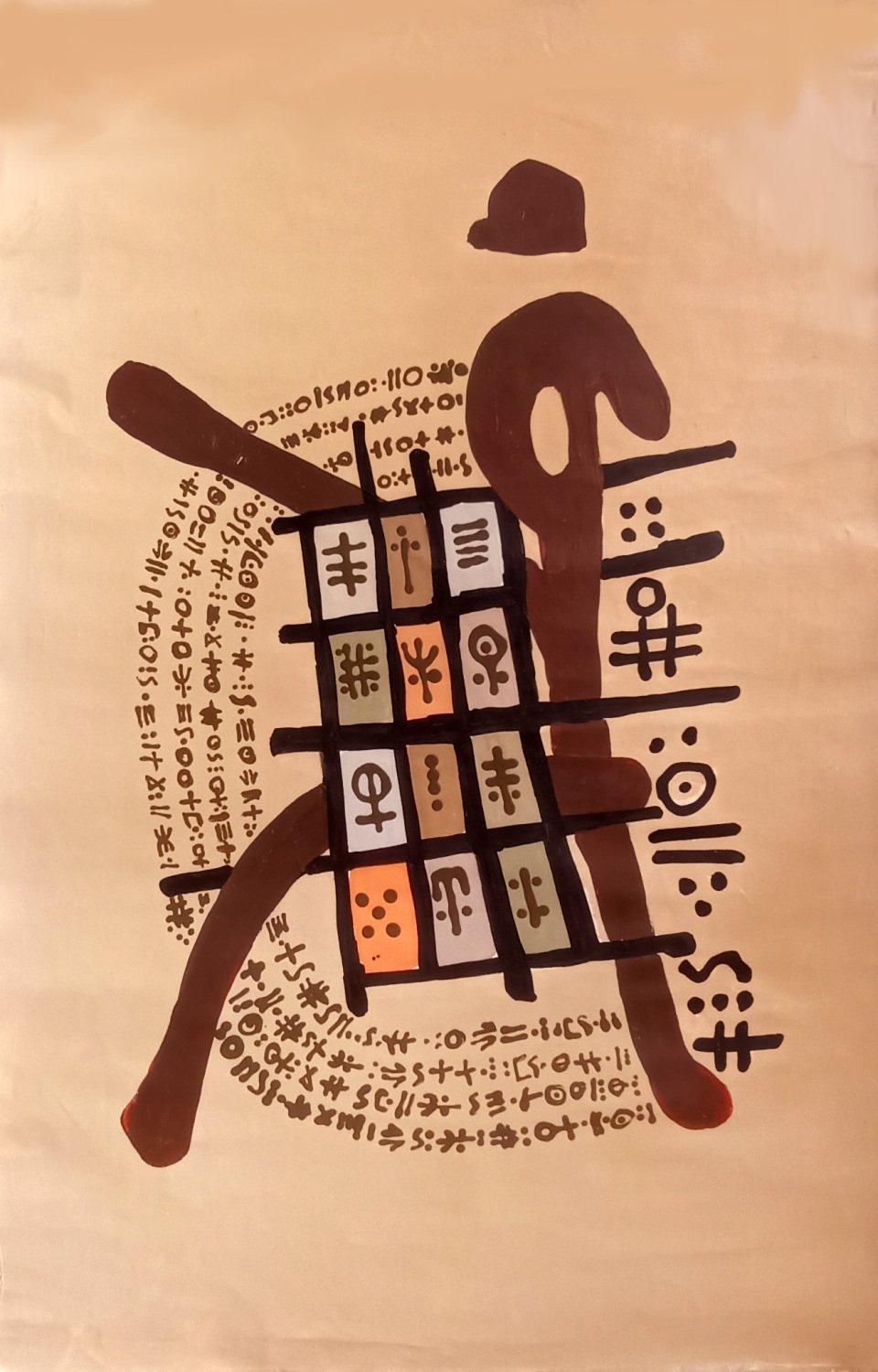

Figure 1: SJ rock

Judging from the quality of the preservation of the SJ inscription, we can reasonably conclude that the rock was not transported a long way. This type of rock is present in an area that is well-known for its Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous deposits (Montenat (2005)) .

The SJ rock is a rectangular, cuboid rock with one end that is flat and an opposing end that is tapered. The flat character of one end of the rock indicates that it was probably originally set up vertically, with its flat side on the ground and its tapered side peaking as a top-end.

Figure 2: flat end of the SJ rock

The social context of the SJ rock

Sidi Jaafar is a village located in the community of Tounoudt, Ourazazat Province, Draa Tafilalt Region, Morocco. The village is a part of the Chiefdom of Ait outfaou Tarka, which contains six villages. According to the 2004 official referendum (Referendum 2012), 179 individuals live in the village. The majority of tribes populating the Toundout community, where Sidi Jaafar is located, are Imghran-active communities whose members, especially the youth, seek job opportunities either inside the Ouarzazate Province, in other Moroccan regions, or in foreign countries such as Algeria, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and the European Union. Imghran individuals are skilled in plastering, a cultural trait they have inherited from their ancestors. It is typical of these tribes for at least one or two members in each of their families to work in plastering. One young Imghran man informed us about the occupational activities common in his tribe by saying, “The area (where Imghran live) is a source of the workforce, especially for (the cities of) Agadir, Meknes, Casablanca, and the eastern region of Morocco. Their (work) activities revolve mainly around construction work and agriculture. Plastering, however, remains one of the most important work fields chosen by individuals from Amkchoud (i.e., the name of the young man’s village, only six kilometers away from Sidi Jaafar). The professionals of the area are renowned for mastering this work both at the national and the international levels.” This information about Imghran villages is relevant to our present article because the inscription pecked on the upper surface of the SJ rock, arguably agabs, is reminiscent of a semantically and phonetically similar word that is still used in modern Moroccan Arabic (MA), whose lexicon is heavily influenced by Amazigh:[2] namely, gəbs̃, the MA word for “plaster” and “gypsum.”

| Key to Nabti’s chart V: phonetic content L/or: Western Lybic L/oc: Eastern Lybic Sah: Saharan H: Hoggar G: Ghat D: Adrar Y: Ayer W: Iwelmedan T: Tanslemt AB: Académie Berbère, Neotiphinagh |

Figure 3: Nabti’s Chart

Tiphinagh

The word pecked on the SJ rock, arguably agabs, is inscribed in the Touareg Tiphinagh[3] (henceforth, TT). The TT script is believed by many scholars to be a survival of the Libyco-Amazigh script (Casaajus 2015), a text of which figures on the Dougga mausoleum alongside a Phoenician translation of the same text (Poinssot 1910). The TT inherited from the Libyan script its consonantal nature (i.e., neither of the traditions used vowels) and the autonomous character of the grapheme (i.e., letters were not connected to each other). The earliest extant inscription of the Libyco-Amazigh is the Azib nikkis, which has been dated back to the sixth century B.C. (Rodrigue and Pichler 2011). Despite the considerable variation in Libyco-Amazigh script throughout its history, scholars generally recognize three major traditions: Western Libyan, Eastern Libyan, and Saharan, with the latter giving rise to Touareg Tifinagh (Casajus 2021).The latter itself covers a remarkable number of varieties that have been summarized by Amr Nabti (Nabti 2007) in the following chart.

Figure 4: 5 graphemes are clearly identifiable on the SK rock

The date of SJ rock

The earliest extant Libyco-Amazigh inscription, which is the Azib N’Ikkis found on the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco, has been traced back to the sixth century B.C. (Camp 1978). Based on the current state of our knowledge, we can accept the hypothesis that the use of the TT script disappeared in North Africa sometime between 550 and 750 A.C. (Toujdi 2006). This in itself indicates that the SJ inscription could not have been pecked later than the end of the eighth century A.C. No indicators of an “editorial” addition, superimposition, or innovation can be identified in the inscription.

The SJ rock’s “word”

Five TT characters are clearly identifiable on the SJ rock, namely: ⴰ - ⴶ- ⴰ - ⵀ - ⵙ. Assuming that the peaked end of the rock is its top and the flat end is its bottom, we conclude that the SJ

word is inscribed top-down. The deliberate linear order, the visibility of the TT characters, and the centrality of composition (i.e., the fact that the characters are arranged vertically at the center of the rock) are clear indicators of a deliberately pecked linguistic sign, probably a word. Despite the large number of scratches resulting from erosion or vandalism, the following five characters are clearly identifiable:

(1) ⴰ

(2) ⴶ

(3) ⴰ

(4) ⵀ

(5) ⵙ

The characters (1) and (3) are dots, rather than small circles, and are more likely to be instances of the grapheme representing /a/ in Nabti’s chart (figure 3). This grapheme figures in the TT varieties H, G, D, W, Y, and T. The character (2) is clearly the grapheme representing /g/ in three TT varieties, namely G, D, and W. The character (4) is the graphemic symbol for /b/ in the TT varieties G, D, Y, W and T. The character (5) should not be interpreted as an instance of the grapheme for /b/ even if it used as such in L or/oc and Sah TT varieties, the reason being that these varieties do not contain the grapheme instantiating (4), which is the symbol for /b/. In H, the grapheme instantiating (5) is used ambiguously for both the phonemes /b/ and /s/. In the G, D, Y, W, and T TT varieties, the grapheme instantiating (5) is used as a symbol for /s/. Given our analysis of the SJ inscription, we suggest (Sc.1) as a schematization of the graphemic composition on the SJ rock, and we suggest (Gr.1) as its corresponding graphemic representation.

(Sc.1) (Gr.1) ⴰ ⴳ ⴰ ⴱ ⵙ

Another possible schematization of the SJ inscription is (Sc.2), where one more dot is added to (3/Sc.1/Gr.1), interpreting the latter and the additional lower dot as being a ligature of a single grapheme (6):

(Sc.2): (Gr.1) ⴰⴳⵓⴱⵙ

(6)- ⵓ

The character (6) is used in the H, G, D T, Y, W, and T varieties of the TT script as a symbol for the phoneme /w/. However, the possibility of Sc.2 (and, thus, Gr.2), where the lower scratch is interpreted as a second dot beneath the upper one, should be excluded for the following reasons:

(i) The lower dot of (6) would be inexplicably larger than (1) and (3), the latter presumably being the upper dot of (6),

(ii) The “writer” would not have had any good reason not to make the right end of the character (2) equidistant from the two dots of (6).

(iii) The general tendency of the inscription is to lean slightly to the right as it moves down towards the bottom of the rock and not to the left, as would have been the case if we interpreted the lower scratch as a lower dot (i.e. as in Gr.2).

Sticking to the representations (1)-(5), we can make an empirically consistent conclusion about the type of the TT variety used in SJ rock and, thus, about the phonetic content of each symbol therein. Given that (1)-(5) is an adequate representation of the SJ inscription, and knowing that all the characters in its composition figure together only in the G, D, and W traditions in Nabti’s chart, we can safely conclude that the phonetic contents of the characters are as follows:

| Character | Phonetic content |

| ⴰ | /a/ |

| ⴶ | /g/ |

| ⴰ | /a/ |

| ⵀ | /b/ |

| ⵙ | /s/ |

The same conclusion is confirmed when we use the more detailed chart of Toudji (Toudji 2007) representing the three main varieties of the TT script traditions. Just as in Nbati’s chart, the characters (1)-(5) appear together only in the TT varieties G, D, and W.

Figure 5: Toujdi’s chart

A linguistic analysis of the SJ word

If our analysis (Sc.2 and Gr.2) is on the right track, the SJ inscription can be given the phonetic interpretation in Phr.1.

(Phr.1) /agabs/

Morphologically, Gr.2 has the form of a singular, masculine noun of the type taking an initial prefix a-. At least three noun types exist in Amazigh: (i) those taking the prefix a- (like a-səlmad, or “teacher”), those taking the prefix i- (like i-fri, or “cave”) and those taking the prefix u- (like u-∫∫ən, or “jackal”) (Boussayer 2021). Gr.2 can plausibly be interpreted as a noun of the first type.

Since it is not clear whether or not the G,D,W varieties used the two-dot sign (character (6)) for /u/ (as Nabti (in Nabti (2007)) indicated by placing the grapheme representing /w/ between parentheses in the last line of his chart), it is best to exclude the possibility of phonemically interpreting Gr.2 as follows:

(Phr. 2) /agabus/

and represent it as Phr.3 instead:

(Phr.3) /agabs/

Phonotactically, the sequencing of sounds in Phr.3, agabs, does not seem to violate any of the phonetic sequencing constraints of Amazigh. The noun format a-CaC(ə)C is very productive in this language (compare, for example, words such as amar(ə)g, or “song,” and asan(ə)f, or “shortcut,” asar(ə)g, or “a place where charcoal is stored,” and afar(ə)g, or “a branch”).

Since long consonants (i.e., emphatic consonants) were not marked (for example by doubling identical successive consonants) in the TT script, Gr.2 could also be phonemically represented as: /aggabs/, where /g/ is geminated. Words with this format, a-CiCiaC1C2, are also available in Amazigh (compare, for example, the words assays, or “a dancing floor,” and asssatf, or “tearing out”).

A third possible phonemic representation of Gr.2 is: /agabbəs/. This form is possible because the grapheme representing /b/ could be emphatic, as the schwa vowel was not represented in the G,D,W varieties, and because the lexicon of the Amazigh language contains words with a similar format, a-C1aCiCi(ə)C2, (compare, for example, asammər, or “name of a region in the South East of Morocco,” and anajjəl, or “blackberries”).

In short, Gr.2 is a masculine, singular noun that can be phonemically represented as /agabs/, /aggabs/, or /agabbəs/. Thus, we will summarize the possible phonemic representations of Gr.2 as follows:

(Phr.4) /a(g)ga(b)bs/, where either /g/ or /b/ can be geminated.

A Linguistic Analysis

A plausible hypothesis about the SJ inscription that we will support in the next paragraphs is that some nomads or shepherds probably set it up to mark the presence of gypsum in the surrounding area or the direction to a place containing it. If so, then the SJ sign is a geocontourglyph that human individuals deliberately pecked on the SJ rock with the intention of guiding travelers or explorers to a site where they can find or buy gypsum.

We can support this conclusion by using two types of considerations, namely the following:

The first consideration, a geological one, is that according to a geological synthesis (Montenat et al. 2005), gypsum is abundant in the Toundoute area, where the SJ rock is located. This can be explained by the abundance of Cretaceous and Triassic geological formations containing a deposit of salt and gypsum mined in the northern zone of Toundoute. According to Britannica, gypsum is a “common sulfate mineral of great commercial importance, composed of hydrated calcium sulfate (CaSO4·2H2O).” It occurs in “extensive beds associated with other evaporite minerals […] particularly in Permian and Triassic sedimentary formations.” Commenting on Gypsum’s utility, Britannica specifies that “[c]rude gypsum is used as a fluxing agent, fertilizer, filler in paper and textiles, and retarder in Portland cement. About three-fourths of the total production is calcined for use as plaster of paris and as building materials in plaster, Keene’s cement, board products, and tiles and blocks.” Imghran artisans and builders still use gypsum in making plaster designs for inside and outside walls and ceilings.

Amazigh (Berber) houses in rural areas are well known for the plaster frames that serve to protect the wood window frames, which are built into rammed earth walls, from being displaced if the rammed earth is washed away by heavy rains. This means that Amazighs used gypsum not only for aesthetic, decorative reasons but also to meet the vital need of improving the durability of the main building construction material, rammed earth. This explains why they needed a good knowledge of the sites where gypsum could be found and why they had to set up geocontourglyphs to mark those sites for future use or as a map to orient others.

The second consideration is that the word agabs, phonemically represented in Phr.4, is reminiscent of a semantically and phonetically similar word that is in use in modern Moroccan Arabic (MA), the lexicon of which is heavily influenced by Amazigh,[4] namely: gəbs̴, the MA word for “plaster” and “gypsum.” Chafiq (1989) accumulated remarkably extensive lexicographical data that exemplify the presence of an Amazigh lexical substratum in modern MA. In the introduction to his work, he distinguished three types of MA words that have Amazigh ancestors, namely:

(i) MA words with an Amazigh ancestor that have maintained their original morphological Amazigh form (for example, the word tagra, or “vessel,” which has maintained both its Amazigh morphological form and meaning),

(ii) MA words with an Amazigh ancestor that have changed their original morphological form by adapting an Arabic morphological form (for example lməzgur, or “corn,” which maintained the root məzgur but changed its form by adding the Arabic definite article l-), and

(iii) MA words of Amazigh origin that are used in modern MA with two interchangeable forms: its original Amazigh form and its Arabized form (for example, amazir, or “the fertilizer,” which can also be used with the Arabic form lmazir.)If our analysis of the SJ inscription in terms of (Phr.4) is on the right track, and if the MA word gəbs̃ is a cognate of the Amazigh word agabs, then we can describe gəbs̴ as a word of type (ii). Specifically, we can describe it as an MA word with an Amazigh ancestor, agabs, that has changed its original morphological form by dropping the masculine, singular prefixal marker a-, by reducing the vowel /a/ immediately following the first consonant /g/ into a schwa, and by velarizing the final /s/.

One potential argument against this analysis is that gəbs̴ might be a development of the Classical Arabic word ʒibs̴ and not a cognate of agabs. This cannot be true, however, because the Classical Arabic sound /ʒ/ does not change into /g/ in MA but systematically keeps its palato-alveolar character. Examples of this historical linguistic situation are shown in the following chart, where Classical Arabic words with the sound /ʒ/ are compared with their MA equivalents:

| Classical Arabic words | Moroccan Arabic words |

|---|---|

| ʒabal “mountain” | ʒbəl “mountain” |

| ʒamal “camel” | ʒməl “camel” |

| raʒaʕa “come back” | rʒəʕ “come back”2 |

| haʒar “leave”1 | hʒər “leave” |

| borʒ “tower” | bərʒ “tower” |

| sirʒ “saddle" | sərʒ “saddle” |

The second consideration is that the word agabs (or its other forms in Phr.4) itself sounds like an adaptation of the Latin gypsusm /ˈd͡ʒip.sum/ and the Greek γύψος /ɡýp.sos/. The former is a nominative, singular form, the plural version of which is gapsa; the latter is a second-declension noun meaning “chalk” or “cement.”

While we could not find any possible linguistic ancestor for these Latin and Greek words in the Proto-Indo-European Etymological Dictionary (a Revised Edition of Julius Pokorny’s Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch), the Hamito-Semitic Dictionary (Orel 1995) provides us with a good line of investigation where we find a possible Afro-Asiatic ancestor for gabs, namely the Proto-Afro-Asiatic root *gab, meaning “earth” or “clay.” The following chart lists possible Afro-Asiatic cognates with their meanings (Orel and Olga (1995)):

| Cognate | Language family | Language | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gabību | Semitic | Akkadian | earth, ground |

| Rʒabīb, ʒabūb | Semitic | Arabic | earth, thick earth |

| Gbb | African | Egyptian | earth, earth-god |

| guva, gǝva | Central Chadic | Gisiga | field |

| gāb | East Chadic | Tumac | clay |

| g̣ʌb | East Chadic | Ndam | clay |

| Kappe | Dullay Languages | Gawwada (Gawata) | earth |

Since Amazigh is traditionally classified as a Hamito-semitic (Afro-Asiatic) language, it is striking that the root *gVb, in the sense of “clay,” “earth,” and “ground” does not exist in this language. It likewise does not exist in “Dictionnaire des racines berbères Communes” (Haddadou 2007) where Haddadou compiled 1023 roots that Amazigh dialects in North Africa have in common (Haddadou, M.A. (2007) Dictionnaire des racines berbères communes, Haut Commissariat à l’Amazighité). In his seminal, copious dictionary (Chafiq (1987)), Chafiq included the Amazigh words akal and tamurt as lexical equivalents of the Arabic words turaab, or “earth” and “ground” (vol. 1, p. 190); aʃlʃal, talaqqt, tawʃkt, and idqqi as different lexical equivalents of the Arabic faxxaar “clay” (op. cit. vol. 2 , p. 226); and the word talaɣt as an equivalent of the Arabic word ʈiin, or “mud” (vol. 2, p. 51). Nowhere in Chafiq (1987) do we find an entry with the root *gVb with the meaning of “clay,” “earth,” or “ground.”

Yet the Haddadou dictionary (Haddadou 2007:67) includes the root gbw (entry 227), which occurs in at least 3 dialects of Amazigh. I summarize Haddadou’s lexicographical information about this entry in the chart below.

The meanings that the derivatives of the root gbw have are: “mature,” “mold,” “ripen,” and “rot.” One semantic feature that these meanings have in common is “become soft” or “soften.” A reasonable hypothesis to be advanced, then, is that: in the African part of the African Asiatic language family, there are some languages (the only representative of which we now know is Amazigh) where the root *gb means “mature,” “ripen,” “mold,” and/or “rot,” and it was from this root that African Asiatic languages derived the root *gVb with the meaning of “clay,” since the clay is soft and squishy.

| Lexical entry | The phonetic value of the first consonant | Lexical category | Dialect | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ed͡ʒbu | d͡ʒ | verb | to | “achever de mûrir après avoir été cueilli (légume, fruit cueilli avant maturité)” “completely mature after being picked (vegetables, fruits picked after maturity)” |

| sed͡ʒbu | d͡ʒ | verb | To | “faire achever de mûrir après avoir été cueilli, moisir” “to finish ripening after having been picked, to mold” |

| id͡ʒebi, id͡ʒeban | d͡ʒ | noun | To | “datte qui a achevé de mûrir après avoir été cueillie” “date that has finished ripening after being picked” |

| Agbu | G | adjective | Tw and Y5 | “être moisi” “to be moldy” |

| Segbu | G | verb | Tw and Y | “moisir, rendre pourri” “to mold, to rot” |

One piece of evidence supporting this hypothesis is that there are possible cognates for the Amazigh Touareg gbw in the sense of “mature,” “ripen,” “mold,” and/or “rot,” even in Indo-European languages such as Estonian and Ludian. In Estonian and Ludian, we have küps, or “mature.” For Koivulehto, this word came from earlier *küpte- or *kepte-, from Baltic *kʷep-tá, from the Proto-Indo-European *pekʷ- (“to cook, to become ripe”). This root and its later developments in Indo-European languages are well documented in Pokorny’s dictionary.

References

Boussayer, A. 2021. “Gender and Number Marking in Amazigh Language.” International Journal of Linguistics and Translation Studies 2(1):91-106.

Camps, G. 1978. “Recherches sur les plus anciennes inscriptions libyques de l’Afrique du Nord et du Sahara.” Bulletin archéologique du CTHS, 10–11 (1974-1975):143-166.

Dominique Casajus. 2015. L’alphabet touareg. Paris: CNRS Editions.

Chafiq, M. 1987. Al-mu‘jam al-‘arabi al-amazighi. Rabat: Publications of the Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco.

________. 1999. Addarija al-maghribiyya: majal attawaarud bayna al-amazighiya wa al-‘arabiya. Rabat: Publications of the Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco.

Haddadou, M. A. 2006. Dictionnaire des racines Berbères commune suivi d’un index français-berbère des termes relevés. Tizi-Ouzou: Les Oliviers.

Chaker, S., & S. Hachi. 2000. “A propos de l'origine et de l'âge de l'écriture libyco-berbère. Réflexions du linguiste et du préhistorien.” Etudes berbères et chamito-sémitiques, mélanges offerts à Karl-G. Prasse, S. Chaker, éd., 95-111. Paris: Éditions Peeters.

Haut-Commissariat au Plan. 2004. Recensement général de la Population et de l'Habitat de 2004. Rabat: Royaume du Maroc. https://www.hcp.ma/Recensement-general-de-la-population-et-de-l-habitat-2004_a633.html

Montenat, C., M. Monbaron, R. Allain, N. Aquesbi , J. Dejax, J. Hernandez, and P. Taquet. 2005. “Stratigraphie et paléoenvironnement des dépôts volcano-détritiques à dinosauriens du Jurassique inférieur de Toundoute (Province de Ouarzazate, Haut-Atlas–Maroc).” Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae 98(2):261-270.

Nabti, A. 2007. “Analyse d’une méthode d’apprentissage de l’alphabet Tifinagh.” ACTES du Colloque international sur Le libyco-berbère ou le Tifinagh: de l’authenticité à l’usage pratique, Haut Commissariat à l’Amazighité, 255–274. Alger: Centre de Presse d’El-Moudjahid.

Poinssot, L. 1910. “La restauration du mausolée de Dougga.” Comptes rendus de des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 54(9):780–787.

Orel, V.E. and O.V. Stolbova. 1995. The Hamito-Semitic Etymological Dictionary: Materials for a Reconstruction. Leiden: Brill.

Pokorny, J. 2007. Proto-Indo-European Etymological Dictionary: A Revised Edition of Pokorny’s Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch. Badajoz, Spain: Indo-European Language Revival Association.

Rodrigue, A. and W. Pichler. 2011. “Le “supplicié” des Azibs n’Ikkis (Haut Atlas marocain) et les inscriptions qui l'accompagnent.” Parcours Berbères. Mélanges offerts à Paulette Galand-Pernet et Lionel Galand pour leur 90è anniversaire. Berber Studies 33:33-38.

Toudji, S. 2007. “Écritures libyco-berbères: origines et évolutions récentes.” In ACTES du Colloque international sur Le libyco-berbère ou le Tifinagh: de l’authenticité à l’usage pratique, Haut Commissariat à l’Amazighité, 131-151. Alger: Centre de Presse d’El-Moudjahid.

Zajceva, N. G. and M. I. Mullonen. 2007. “доваренный, допечённый, зрелый,” In Uz’ venä-vepsläine vajehnik/Novyj russko-vepsskij slovar. New Russian-Veps Dictionary. Petrozavodsk: Periodika.

Footnotes

[1] The description “Berber” is still commonly used to refer to the native inhabitants of North Africa. However, because this term is judged by Amazigh people themselves as a humiliating ethnographic slur (ethnophaulism) due to its Latin connotations (barbarian, or “a member of a people not belonging to one of the great civilizations”), we will avoid using it and use the term “Amazigh” instead.

[2] The fact that the lexicons of Amazigh and MA have influenced each other has been extensively documented by Chafiq 1989.

[3] The term “Libyco-Amazigh” has been used in scholarship to refer to both an ancient language and its writing system. In this paper, when discussing Touareg Tifinagh, I refer specifically to the script, which represents a later developmental stage of the Libyco-Amazigh writing system that emerged after the 7th century CE. According to Pichler (2011), the earlier Libyco-Amazigh script evolved through three stages from the 6th century BCE to the 7th century CE, before developing into what we now know as Tifinagh.

[4] The fact that the lexicons of Amazigh and MA have influenced each other was extensively documented by Chafiq in Chafiq 1989.

[5] By "Tw,” Haddadou seems to mean a certain variety of Touareg Amazigh, but he does not specify in his list of “Abréviations” on page 3 what the symbol is intended to stand for. By “Y,” he seems to mean the Touareg Amazigh spoken in Taytoq. Again, no clue is given in the “Abréviations,” a major technical shortcoming in Haddadou’s work.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 3 • Issue 1 • Spring 2025

Pages 70-82

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Cadi Ayyad University