Exploring the Gendered Aspects of Amazigh Linguistic and Cultural Transmission through Contemporary Tachelhit Pop Song

AUTHOR: Ella Williams

Peer Reviewed Article

Amazigh Women’s Agency: Exploring the Gendered Aspects of Amazigh Linguistic and Cultural Transmission through Contemporary Tachelhit Pop Songs

Ella Williams

University of Oxford

Abstract: This article examines Amazigh women’s agency and the gendered dimensions of Amazigh linguistic and cultural transmission using the case study of contemporary Tachelhit pop songs. It argues that recent scholarship, which seeks to “unearth” Amazigh women’s agency through highlighting their role in cultural and linguistic knowledge (re)production, contributes to the feminization of these processes. This feminization, further reinforced by popular culture such as music, creates a gendered threat. The article explores the concept of “threat” in two ways: first, as a threat to Amazigh women themselves, and second, as a threat to ongoing efforts to revitalize the Amazigh language. This research aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the intersections of gender, popular culture, and language in the context of contemporary Amazigh identity and revitalization initiatives.

Keywords: Gender, agency, music, women, authenticity.

Linguistic and cultural threats to Imazighen in the post-colonial period

Imazighen or Amazigh are the indigenous inhabitants of North Africa, and “Tamazight” refers to numerous related language varieties spoken throughout North Africa. Tamazight language communities are found across Morocco, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Mali, Niger, and Mauritania. There are more than forty million people who speak an Amazigh language across North Africa, the majority of which live in Morocco (Lafkioui 2018). The three main varieties spoken in Morocco are Tarifit, Central Atlas Tamazight, and Tachelhit. According to calculations based on the Moroccan census, these varieties are spoken by approximately 1.3 million, 2.6 million, and 4.7 million speakers, respectively. However, due to historical underreporting of Amazigh speakers, researchers estimate that Tamazight is the mother tongue of at least half (Sadiqi 2003) and up to 70% of the Moroccan population (Lafkioui, 2018). Despite being the indigenous language of North Africa, Tamazight has suffered and survived centuries of marginalization, assimilation, and prohibition.

Before moving on to the central theme of this article, I will briefly outline the linguistic and cultural threats Imazighen have faced in the post-colonial period so as to provide context for the contemporary language revitalization efforts and challenges in Morocco. Following independence in 1956, national identity in Morocco was constructed around a univocal narrative, largely due to the perceived risk of Amazigh identity to national unity, a belief forged by the link between “Berberism” and colonialism. Islam and the Arabic language were declared the key pillars of nationhood, since unity was seen as a prerequisite to ridding the nation of colonial influence. This homogenizing process of nation-building created a hostile political climate, where “recognition of ethnic or linguistic “difference” was considered a challenge to the legitimacy of the state and the unity of the nation” (Brett & Fentress, 1996). In Morocco, the King’s speech in 1958 following independence declared that the country would become “a Morocco that is Arabic in its language and Muslim in its spirit” (quoted in Zartman 1964) and in 1961, Morocco was officially defined an Arab and Islamic nation-state (Karrouche 2017). Within this definition of the newly independent nation, expressions of Amazigh ethnolinguistic identity were forcibly excluded, and those expressing Amazigh identity were accused of disloyalty to the ideal of national unity and proponents of “regionalist identities” that were “obstacles to national integration” (Silverstein 2003). Amazigh identity was seen to preclude being Moroccan and those who considered themselves to be of Amazigh origin were required to assimilate culturally and linguistically in order to become members of the nation state (Hoffman 2008).

Linguistic unity was one of the central pillars of Maghrebi post-independence nation building; strong ties between language and national identity were forged during and after the struggle for independence, and the nationalist independence movements considered the language question a priority. National unity was assumed to be achieved through the principle of “one nation, one state, one language” (Bassiouney 2009). Nationalism in post-independence Morocco therefore came hand in hand with the policy of Arabization, which aimed to assert Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) as the single, official language and to “Arabize” all domains, imposing MSA as the sole medium of education and official language of government and business. The Amazigh language and culture were “forcibly excluded, for half a century, from legitimate conceptions and expressions of society and nation” (McDougall 2010) and Tamazight varieties were “denigrated as indices of backwardness, rurality and defiance of a unified Arabo-Islamic identity” (Hoffman 2010). El Guabli has argued that the primary effect of Arabization policies was not the replacement of French, but the dislodgement of Tamazight from public life (El Guabli 2023).

In addition to this linguistic suppression, Imazighen were largely written out of the national historiographical narrative, including their participation in the national liberation struggle. Textbooks produced by the Ministry of Education, for example, did not mention Morocco’s pre-Islamic or pre-Arab history (el-Khatir 2005). Hoffman (2008) argues that “there was a concerted effort from the rise of the nationalist movement in the 1920s until the early 21st century to relegate the Amazigh component of Moroccan heritage to a footnote in the evolution of the modern nation.” Jacobin-like efforts to impose cultural and linguistic unity on Moroccan society were felt in Morocco up through the 1980s and 1990s. Ahmed Boukous, a linguistics professor and one of the founders of AMREC (the Association Marocaine de Recherche et d’Echange culturel), was not allowed to hold a passport for many years, and in 1994, seven teachers who were members of the Amazigh association Tilleli were arrested in Goulmima for carrying banners written in Tifinagh. The names of towns, villages and geographical landmarks, which in Morocco are overwhelmingly of Amazigh origin, were Arabized and a dahir, proclaimed as late as November 1996, attempted to block parents from giving their children names in Tamazight (Maddy-Weitzman 2011).

Despite the struggles that Imazighen have faced, Amazigh culture and language varieties have survived marginalization, assimilation, and prohibition. Moreover, paradoxically, the forcible exclusion of Amazigh identity from national narratives following independence, along with the state’s suppression of expressions of Amazigh ethnolinguistic identity, transformed expressions of Amazigh identity from an ethnocultural movement into the politicized, transnational Amazigh movement that we see today across Tamazgha.[1] However, despite the endurance of Tamazight language varieties in Morocco, persistent attempts at erasure and the promotion of negative language attitudes threaten their continued survival. This threat is compounded by the complex processes of migration, urbanization, and intermarriage. Tamazight language survival is now considered to be at a critical stage and a recent report found that out of thirty-two Amazigh language varieties in North Africa, there are only four that are not in danger of disappearing (Amazigh World News 2019).

Language remains central to Amazighité and therefore both top-down and bottom-up approaches to linguistic revitalization are necessary for the survival of Tamazight language varieties in Morocco. Top-down approaches have included the institutional and constitutional recognition of the Amazigh language, the creation of the Royal Institute of the Amazigh Culture (IRCAM) in 2001, the recognition of the Amazigh language as an official language in the Moroccan Constitution in 2011, the gradual introduction of the teaching of the Amazigh language in the public school system and the introduction of Tamazight in the media, including the creation of a Tamazight television channel. Bottom-up approaches are also necessary, and the survival of Tamazight is dependent on the Tamazight-speaking community maintaining language vitality through documentation, revitalization, use, and intergenerational transmission. Grin (1990) maintains that the first objective of a language policy should be to significantly promote the image of a minority language,[2] arguing that “any language policy that provides money but avoids sincere commitment to boosting the image of the language is likely to fail. There seems to be no way around this: for a minority language to survive, its image must be positive.” Tamazight language efforts should therefore prioritize the development of positive attitudes among native speakers, since family and intergenerational transmission are crucial for language maintenance and revitalization (Fishman 1991; Romaine and Nettle 2000). Romaine and Nettle (2000), for example, argue that without a focus on the family and community, revitalization efforts at the levels of formal education and government will be fruitless. The bottom-up process of Amazigh language and cultural revitalization is, however, highly gendered, and the process of language transmission has become a highly feminized one, placing the burden of linguistic and cultural survival on Tamazight-speaking women.

In the following sections, I will explore the gendered nature of Amazigh cultural and linguistic preservation and transmission through the medium of Tachelhit pop songs. I will first explore the concept of “the Amazigh woman” in academic literature and the popular imagination before moving on more specifically to examine the gendered process of Tamazight language transmission and the resulting feminization of the language itself. Finally, I will argue why this presents a threat both to Amazigh women and to the survival of the Tamazight language.

The “Amazigh woman”

The image of the Amazigh woman occupies an interesting and often contradictory space in both academic literature and popular discourse. The Amazigh woman of the past is remembered for being independent, hardworking, and beautiful, and pre-Islamic North Africa is promoted as an example of matriarchal societies, based on amass (matrilineal lineage). Amazigh women played important roles as queens, knights, and warriors who displayed unprecedented levels of courage. Amazigh women’s oral heroic stories highlight key figures such as Tanit,[3] Dihya,[4] and Tin-Hinan[5] and the roles they play in North African history as women who governed tribes and territories, led armies, and excelled in oral literacy and poetic creativity (Yassine, 2001). In Tuhfat al-Nazzar, for example, Ibn Battuta writes about being astonished at the status of Amazigh women and the important position they occupied among the members of the tribe, clan, and family.[6] Writing on women of the Masoufa tribe, he notes that “their status is greater than that of men” and that “there is no dominant, authoritarian, or oppressive authority over the women of the tribe.”[7] The status and competence of Amazigh women in political, social, economic, and cultural spheres is also noted in sources such as Kitab al-Maghrib by al-Bakri, al-Ibar by Ibn Khaldun, and Nuzhat al-Mushtaq by al-Idrisi.[8] Amazigh women in the precolonial era were skilled in the field of literature and culture. One example is Mririda n'Ait Attik, an Amazigh oral poet who was born around 1900 in the High Atlas and who composed oral poetry in Tachelhit. Her work was recorded and translated into French in the 1930s by René Euloge. Her poetry addressed topics considered taboo at the time, such as divorce and unrequited love. Other earlier examples include Almoravid Princess Tamima bint Yusuf ibn Tashfin and Zaynab an-Nafzawiyyah, who is also noted in historical sources for her decisive role in the management of the political and administrative affairs in the Almoravid state.[9] Amazigh women also played an instrumental role in resistance against the colonizer (Yassine 2001) by participating in armed resistance, caring for the wounded, and providing refuge for fugitives.

In contrast to the strong image of Amazigh women in the pre-Islamic and colonial period, the image of the Amazigh woman in the contemporary imagination is very different. Amazigh women are often represented as “illiterate,” “in need of help” (Sadiqi, 2014) and as passive beneficiaries of aid, and much of the literature focuses on their marginalization. It cannot be denied that high levels of poverty and low literacy disproportionality affect Amazigh speaking areas of the countryside, and therefore we cannot discuss Amazigh cultural identity without considering socioeconomic circumstances (Gagliardi, 2019). Many Amazigh women are located in rural areas and suffer from the intersecting vulnerabilities of being women, indigenous and rural, resulting in economic, educational and healthcare exclusion. However, the focus on Amazigh women's vulnerabilities, such as rural illiteracy, has resulted in the homogenization of Amazigh women and the creation of a composite singular “Amazigh woman,” who is “only understood as a monolithic folkloric subject,” (Sadiqi, 2014) reinforcing the stereotypical image of Amazigh women as powerless (Gagliardi, 2019), reducing them to “victims” and erasing their agency. A paper presented in 2015, for example, was entitled “Moroccan rural Amazigh women: the oppressed of the oppressed.”

The reduction of the Amazigh woman in both the popular imagination and academic literature to rural, illiterate victims of underdevelopment is not an accurate reflection of the role or status of indigenous Amazigh women in contemporary North Africa. Amazigh women play an instrumental role in the survival of families and communities that often face conditions of scarcity, marginalization, and social and economic exclusion, as well as harsh mountainous or desert environments. Women in Amazigh communities play important roles in income-generating activities to ensure their families’ livelihoods, including raising livestock, herding, weaving, and other agricultural activities, which are often overlooked since they fall outside the domain of formal salaried employment. Amazigh women also continue to have powerful authority as leaders of the household and homemakers, a role that in the Amazigh worldview is endowed with powerful symbolic authority and not to be considered inferior to roles outside the home. Additionally, in his work on rural households, David Crawford (2007) argues that Amazigh women play a crucial role in the social organization of rural life, including labor, tikatin (household political economy), social connections between households, and the physical movement of people across tamazirt due to marriage ties. Despite this, Amazigh women continue to be invisibilized, and scholarship and development interventions continue to depict Amazigh women as lacking agency or voice within their communities.

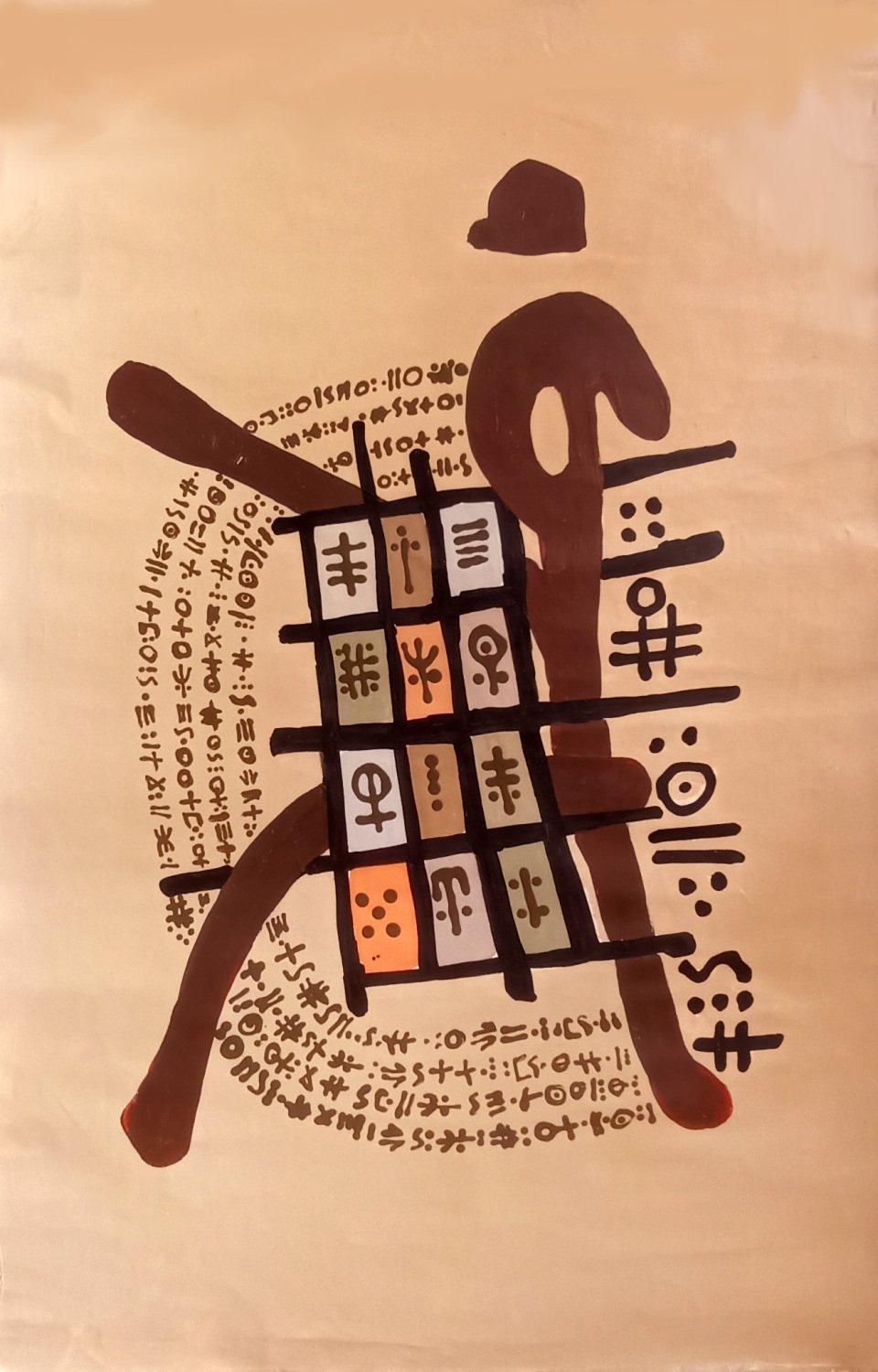

More recent scholarship has attempted to correct the narrative, unearthing Amazigh women’s agency and their contribution to knowledge production, the formation of society, and social organization. These studies have focused predominantly on locating Amazigh women’s agency in the role of rural women in artistic and material (re)production, the transmission of oral knowledge, tales, songs, and the preservation of language and culture. Sadiqi (2007) highlights their essential role in preserving Amazigh language and culture, arguing that the survival of Amazigh oral literature, including tales, songs, and poetry “owes its survival first and foremost to women,” who have kept the “thread unbroken” through intergenerational transmission. She also highlights women’s central role in the performance and transmission of rituals, including rituals associated with healing, worship, fertility, lamentation, and travel (Sadiqi 2014). In her 2006 book, Amazigh Arts in Morocco: Women Shaping Berber Identity, Becker locates Amazigh women’s agency in their central place in art-making, including weaving, tattooing, song, decorative arts and dance, and the role this plays in the construction and transmission of Amazigh identity. She argues that it is through “control over the visual symbols of Berber ethnic identity” that women garner “power and prestige." Therefore, the “generative power of women is metaphorically extended to the creation of artistic symbols of ethnic identity” (Becker 2006). Similarly, Naji (2012) identifies female Amazigh agency in women’s artistic production through weaving, which locates them as the artists and the symbol-creators and carriers in their communities. Women's artistic creation and use of symbols and motifs, such as the use of tifinagh letters in weaving, jewelry, and henna, are closely related to the two major components of Amazigh identity, namely language and culture.

One crucial aspect of women’s role in cultural (re)production is the preservation of the Tamazight language. Moving now to focus more specifically on the gendered processes of language transmission, it is vital to recognize that Amazigh women have played and continue to play an essential role in the transmission and preservation of the Tamazight language. This role has been highlighted as a key site of agency in recent academic work on Amazigh women. While the role of women in language preservation should not be underestimated, the focus on Amazigh women as guardians of the Tamazight language has resulted in an unconscious “feminization” of the language, with consequences for both Amazigh women and the wider revitalization efforts. In her 2008 ethnographic study, We Share Walls, Katherine Hoffman explores the feminization of Tamazight language transmission in an Amazigh-speaking community in the Anti-Atlas of Southern Morocco. Tamazight-speaking communities in this region are characterized by rurality and high levels of migration, with men migrating to urban centers to find employment. In communities characterized by high levels of migration, as many Tamazight speaking areas in Morocco are, women are almost single-handedly responsible for maintaining the land, upholding traditions, and socializing children into the Tamazight language. This genders the language as female and associates it with rurality.

As a result, in the popular imagination, Tamazight-speaking women have come to personify the rugged, stoic, yet vulnerable homeland and its inseparable twin: the language that is persistent, ancient, and hearty, yet also threatened. While men are geographically and linguistically estranged from the Amazigh homeland, women are both materially and symbolically responsible for maintaining the land and the Tamazight language so closely associated with it, not only for themselves and their families, but for the whole ethnolinguistic group. The results in a “gendered vigilance,” where women's monolingualism, adherence to tradition, and their presence in the rural homeland are seen as vital for the maintenance of Tamazight. While the women in Hoffman’s study expressed feelings of entrapment around their monolingualism and illiteracy, the husbands, fathers, and sons saw this as increasing their purity and value. Even in Tamazight-speaking communities not characterized by high levels of migration, Tamazight is still a feminized language. Tamazight language varieties are most often used in spaces that are considered “feminine,” such as the home, family, and private sphere. Monolingual speakers of Tamazight are almost exclusively female, and it is generally understood that the mother is responsible for ensuring that her children learn Tamazight. If mothers are native Arabic speakers, children often do not learn Tamazight, even if their fathers speak it. In this respect, Tamazight must be the “mother tongue” for a child to learn it and for the language to be transmitted. The feminization of Tamazight fits within a broader pattern whereby rural women are expected to uphold "traditional Moroccan social structures" and "channel these traditions and transmit them through female family networks" (Sadiqi 2003).

In summary, whereas recent academic literature has played a positive role in attempting to correct the narrative around Amazigh women’s supposed lack of agency, there is a tendency to focus on rural women’s role in language preservation and traditional artistic production as sites of agency. This literature overlooks other crucial sites of agency, such as Amazigh women’s political and social role, and also focuses on the role of rural women while overlooking the evolving status of urban Amazigh women. It can also contribute to the feminization of the language and linguistic transmission process, creating a gendered burden for women.

Gendered authenticity in contemporary Tachelhit pop songs

This article builds on work regarding Amazigh women’s agency and the gendered aspects of Amazigh cultural and linguistic preservation to further explore the feminization of Tamazight language transmission, using the medium of contemporary Tachelhit pop songs in Morocco, which I argue can fall into the trap of reinforcing the gendered burdens of linguistic and cultural revitalization and maintenance, as well as perpetuating stereotypes around Amazigh women as rural, folklorized subjects. Using Tachelhit-language songs released in the past four years, my research demonstrates how women are still presented in popular culture as being crucial to the reproduction of the countryside, of the Tamazight language, and of Amazigh identity, in addition to being responsible for bearing the brunt of performing authenticity. This has consequences both for Amazigh women themselves and for language revitalization efforts. This research focuses in particular on new forms of contemporary Tachelhit pop music aimed at a youth audience. Using the lyrics and music videos of recently released songs, I explore how contemporary Tachelhit pop music continues to reinforce the feminization of the language and the gendered aspects of its transmission.

Music is fundamental to the foundation of Amazigh social life. Music permeates everyday activities, plays a key part in the marking of major life stages, acts as a vehicle of communication, and serves as a vessel of Amazigh indigenous knowledge, history, and tales. Music has also played an important role in the articulation of the transnational Amazigh movement, Amazigh linguistic and cultural revitalization efforts, and the articulation of claims to indigeneity (El Guabli 2024). Starting in the 1970s with the creation of the band Usman by AMREC, Amazigh artists began experimenting with the introduction of new instruments and fusion styles, resulting in a new wave of musical modernization that led to a reimagining of the Amazigh music scene and the greater commercialization of Amazigh music in Morocco (El Guabli 2024). The modernization and reimagination of Amazigh music contributed not only to an upheaval of Amazigh music as a genre, but also to a reimagining of Amazighité beyond folklorized representations. In a political climate hostile to the expression of Amazighité, music offered a medium through which Amazigh consciousness was spread among younger generations of urban Imazighen, eventually leading to broad-scale political upheavals such as the so-called “Berber Spring” of 1980. In the contemporary context, music continues to serve as an important vehicle of transnational Amazigh consciousness and political expression. While traditional Amazigh musical forms such as ahwach of the Souss region and ahidous of the South East have been studied extensively, there is still a lack of studies on contemporary, urban Amazigh music (Oubenal 2019).

This research does not set out to provide a comprehensive sample or study of the representation of gender in contemporary Amazigh music, but instead uses popular songs to illuminate how the highly gendered process of Tamazight language transmission, which places the burden of linguistic survival on women, persists in contemporary music and popular culture. Pop music was chosen due to the appeal it has for a youth audience. A search was conducted to identify songs that focused on Amazigh women as their subject, were widely available to audiences through YouTube and/or Spotify, blended contemporary musical elements with more traditional Amazigh music styles, and had accompanying music videos. These criteria were chosen to attempt to analyze songs aimed at youth audiences, since this research is particularly interested in the gendered processes of transmission in contemporary society and youth culture rather than the historical perspective. Existing research, albeit very limited, has explored gendered aspects of cultural knowledge production mainly through women’s traditional art forms (Hoffman, 2002; 2008; Becker, 2006; Laghssais, 2023) rather than from a youth perspective. In the confines of this article, I have chosen to discuss two songs that exemplify this phenomenon.

Timazighin (2021) - Omar Elkadali

Omar Elkadali is a contemporary Tachelhit-speaking artist from the Souss region. His musical style incorporates elements of traditional Tachelhit songs with fusion sounds and instruments, including the electric guitar, acoustic guitar, and keyboard. He is particularly interesting as a Tachelhit-speaking artist because his songs are accompanied by professionally-produced music videos that often reach up to 500,000 views online. The central theme of Omar Elkadali’s 2021 song entitled Timazighin is that when choosing a woman for marriage, a man should choose an Amazigh woman.

The singer proclaims:

ⵢⴰⵏ ⵉⵔⴰⵏ ⵣⵉⵏ ⵢⴰⵡⵉ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖⵜ

ⴰⴷ ⵓⵔ ⵉⵜⵍⴼ ⴰⵡⵉ ⵖ ⵜⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖⵉⵏ

He who loves beauty, let him marry an Amazigh woman.

He will not regret choosing her

As the song progresses, the singer outlines the reasons behind giving this advice. A closer examination of three lines from the song makes it possible to consider the reasons the singer suggests marrying an Amazigh woman and the gendered implications of these statements.

ⵢⴰⵏ ⵉⴱⵏⵏⵓⵏ ⵙⵙⵕⵚⵓⵏ ⵍⵎⵉⵔⴰⵜ

ⴰⵣⵔⵓ ⵏ ⵜⵎⴰⵣⵉⵔⵜ ⴰⵙⴰ ⵉⴱⵏⵏⵓ ⵢⴰⵏ

ⵢⴰⵏ ⵉⵔⴰⵏ ⴰⴷⵡⴰⵙ ⵢⴰⵡⵉ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖⵜ

ⵜⴼⵓⵍⴽⵉ ⵜⵡⵏⵣⴰ ⵏⵏⵙ ⵜⵎⵎⵉⵎ ⵜⵖⵔⵉⵜ ⵏⵏⵙ

The builder recommends paying attention to foundations

You will not find better country bricks

He who wants a strong woman, let him choose an Amazigh woman

Here, the Amazigh woman is compared to a house with strong foundations and good “country bricks,” reminiscent of the traditional earthen bricks used to build houses in tamazirt, therefore linking Amazigh women to rurality and the “stoic ruggedness” described by Hoffman. In addition, by drawing a comparison between women and sturdy foundations, the lyrics reiterate the idea of the Amazigh woman as stationary and firmly rooted in the rural homeland.

Listeners are also advised to choose an Amazigh woman based on her beauty. We are told ⵜⴼⵓⵍⴽⵉ ⵜⵡⵏⵣⴰ ⵏⵏⵙ ⵜⵎⵎⵉⵎ ⵜⵖⵔⵉⵜ ⵏⵏⵙ (her hair is like ripe wheat), again linking women with rurality, nature, and the Amazigh homeland.

In the penultimate verse of the song, the lyrics more explicitly reiterate the gendered processes of language guardianship and transmission. The singer states:

ⵜⵔⴱⴰ ⵜⵓⴷⵔⵜ ⵜⵏⵔⵓ ⴽ ⴰ ⴰⵣⵎⵣ

ⵙⵇⵙⴰ ⵉⵇⴱⵓⵔⵏ ⵍⵍⵉ ⵙ ⵜⵜ ⵉⴳⴰⵏ ⴷ ⵜⴳⵍⴷⵉⵜ

ⵜⴽⴽⵓⵙⴰ ⴰⵡⴰⵍ ⵉⵙⵙⵓⵎ ⵜ ⵉⵏⵏ ⵡⴰⵔⵔⴰⵡ

ⵡⴰⵍⴰ ⵍⵄⵡⴰⵢⴷ ⵜⴼⵍⵜⵏ ⵉⴷ ⵉ ⵜⴰⵙⵓⵜⵉⵏ

She bears many responsibilities as our mothers do

She is a rock in the face of time

Ask her about our grandparents, who made her a queen

She protected her language and passed it on to generations

And preserved its old traditions

Here, the lyrics very clearly locate women as the guardians of language and tradition. In addition, by comparing the woman to a rock and evoking a chain of three generations of women, women are seen as unchanging.

Tamghart n Darngh (2023) - Ayt Wahman/Amina Ibourk

Tamghart n Darngh is a musical and artistic collaboration that involves the female singer Mina Ejourk, the celebrated Amazigh musician and composer Ahmed Abaamrane, the Amazigh actress Zahia Zahiri, and the director/percussionist Khaled El-Barkawi, under the project name “Ayt Wahman.”[10] The song was composed by Ahmed Abaamrane and is based on a poem that was written for this project by a poet who has chosen to remain anonymous. The song was recorded at Studio Fouad in Agadir. Ahmed Abaamrane played the string instruments, Mustapha Amal played the ribab, and on percussion was Khaled El-Barkawi, who was also responsible for filming and directing the music video with Zahia Zahiri.

The song can be described as an ode to the Amazigh woman, praising her for her various qualities and behaviors, which we will consider more closely below. The song is accompanied by a music video featuring Zahia Zahiri, who has starred in several Tamazight-language films as well as the much-loved series Baba Ali.

The Amazigh woman who serves as the song’s subject is described as:

ⴳⵉⵙ ⴰⴷⵔⴼ ⵜⵎⵖⵉ ⵖ ⵜⵉⵔⵙⵜ ⵉⵙⵡⴰⵏ

ⵓⴷⵎ ⵉⵙⴼⴰⵏ ⵖ ⵡⴰⴽⴰⵍ ⵓⵔ ⵜⵓⵃⵍ ⵖ ⵢⴰⵏ

ⵓⵔ ⵜⵓⵙⵉ ⴹⵉⵎ ⵓⵍⴰ ⵜⵛⴰ ⵜⴳⵓⴷⵉ ⵥⵎⴰⵏ

Land, fertile and moist

Barefaced and carefree

She suffers neither grievance nor oppression

Like the Amazigh woman of Omar Elkadali’s Timazighen and the women to be found at Hoffman’s field site, Amazigh women are again linked to the rural homeland as well as to purity and authenticity; they are praised for their stoicism because they fail to complain despite the suffering they endure and the trials of living in rural tamazirt.

Throughout the song and accompanying music video, the woman muse is praised for carrying out various tasks that include cutting food for a cow, collecting water from a stream, making traditional tannourt bread in a wood-fired oven, grinding wheat with a traditional mill stone, milking a cow, and washing laundry in a river. By praising women for their ability to carry out hard work, in the same way women have for generations—that is, without complaint—Amazigh women are again linked to stoic ruggedness and come to physically embody the preservation of cultural and traditional ways of living.

The song describes how “ⴰⵕⴰⵡ ⵖ ⵉⵖⵉⵍ ⵜⴰⴳⴳⴰⵜ ⵖ ⵓⵀⴱⴷⴰ ⴷ ⴰⴷⴷⴰⵀⵔⵉ ⵉⴷⴳⵏⴰⵏ” (she holds her infant in her arms and carries fodder on her back), praising women for both their ability to carry out hard work, or tawri, but also for their traditional role as child bearer. The woman in the song is compared to:

ⵜⴰⴱⴰⵡⵓⵛⵜ ⵏⵙ ⵜⴼⵚⴰ ⵣⵓⵏⴷ ⴰⴷⵔⴰⵔ ⵢⴰⵍⵍⴰⵏ

ⵓⵔ ⵜⵔⵎⵉ ⵓⵔ ⵜⵙⵎⵓⵎⵎⵉ ⵓⵔ ⴰⵜⴽⴽⵎⵣ ⴰⴱⴷⴰⵏ

ⴰⵔ ⵜⵣⴳⴳⵓⵔ ⵜⴰⴼⵓⴽⵜ ⵙ ⵓⴼⵔⴰⵡ ⴰⴷⴷⵉ ⵜⴰⴳⵯⵎ ⴰⵎⴰⵏ

A silent melody, but standing like a mountain high

Never crying, nor complaining

With the rising sun she races to draw water from the stream

Again here, the mountain, unchanging and standing strong, firmly rooted in the face of time, echoes the “country bricks” of Elkadali’s Timazighen. This sense of durability and steadfastness can also be linked to the role of women in maintaining ties to tamazirt, the rural Amazigh homeland, in the face of anxieties around identity loss and alienation, particularly due to male migration to urban centers for work. There is a tension between rural tamazirt, the Amazigh homeland, and urban centers of work, which often serve as sites of geographic and linguistic estrangement that threaten Amazigh linguistic and cultural continuity. Within this tension between urban city and rural village, women serve as an anchor to the village and all that tamazirt encompasses. The importance of tamazirt should not be underestimated; Amazigh indigenous lands and villages are more than mere dwelling places; tamazirt is integral to the ways in which people make sense of their identity and negotiate boundaries of the Amazigh community. A fundamental characteristic of being Amazigh is an active relationship with a tamazirt (Hoffman, 2002).[11]

Both songs are accompanied by professionally produced music videos, and in both the female protagonists are presented wearing traditional Soussi clothing, although the surrounding men in the music video for Omar Elkadali’s Timazighen are dressed in the style of the West. This fits into a wider phenomenon seen across Morocco where younger generations of men are abandoning traditional forms of dress in favor of Western style clothing, yet women continue to be expected to wear traditional clothing on religious holidays and for celebrations such as weddings. In the region of Al Haouz that forms the field site for my own ethnographic work, for example, young girls are introducing a new outfit to the series of dresses worn at weddings, including the traditional clothing of Souss as the final outfit worn by the bride, which is an outfit not typically worn before in the region and adopted from Souss, largely thanks to the influence of social media. Despite the numerous traditional garments worn by brides for weddings in Al Haouz, including the Soussi clothes at the end of the wedding, men most commonly wear a Western-style suit. This echoes Hoffman’s “gendered vigilance” and the uneven pressure imposed upon women to main tradition and purity within Amazigh communities. The persistent presentation of Amazigh women in traditional clothing in contemporary culture such as pop music videos can be celebrated for the continuation of Amazigh cultural traditions, on the one hand, but can also inadvertently complicate our ability to imagine the appearance of the contemporary “Amazigh woman” if she is not adhering to traditional forms of dress, leading us to question whether a woman can represent the Amazigh homeland if not presented in a traditional way. This theme will be elaborated upon in the following sections.

The feminization of Amazigh culture and Tamazight’s transmission as a gendered burden

Returning to this article’s central question of how the feminization of Amazigh cultural and language transmission poses a threat, I will explore this first in terms of a gendered threat made to Amazigh women, and secondly as a linguistic threat to the revitalization of Tamazight language varieties in Morocco. As discussed earlier, recent scholarship has attempted to (re)locate Amazigh women’s agency in the role they play in guarding Amazigh traditions and transmitting the language, a vitally important function that has ensured the continued survival of Amazigh language and culture despite the numerous attempts made to erase it from North African society. While scholars have celebrated this role, they have often overlooked the gendered burden imposed on Amazigh women as keepers and propagators of Amazigh cultural identity, which can be a double-edged sword. Gagliardi (2019) argues that the very conditions that make minority and indigenous women instrumental in the preservation of their culture may condemn them to a position of subalternity. The weight of maintaining traditions falls on the shoulders of women who must bear the weight of preserving their people’s culture. Through their association with artistic production, language maintenance, and the Ashelḥi homeland, women are required to be the living representation of cultural identities: to dress, live, and behave in accordance with tradition (Laghssais & Comins-Mingol 2023). As Becker (2006) argues, the decorated female body itself has become a symbol of Amazigh identity.

The association of women with tradition and authenticity can be harmful, resulting in the “gendered vigilance” that Hoffman (2008) writes about. Amazigh women may be seen as heritage vessels by men and their communities, tasked with maintaining cultural “purity” and “authenticity,” and the “ideal woman” is often one who iconizes heritage and is the antithesis of urbanity (Hoffman, 2008). Amazigh women’s gender fulfillment therefore becomes contingent on her working hard, speaking Tachelhit, spending frugally, and valuing the homeland over other places (Hoffman, 2008), and women may experience pressure to retain outward markers of traditional society through “unpolluted” speech and traditional dress. While men highly value women’s contributions to cultural and linguistic maintenance, they may also see value in keeping women monolingual and restricting their movements to the mountains, particularly in areas with high rates of male migration where "monolingualism ensures wives will remain in their husbands’ homelands, tend the land, and preserve his patrimony and reputation" (Hoffman, 2006). This is particularly important given the connection of Amazigh identity to place, which means that Amazigh identity often remains contingent on maintaining an active connection with tamazirt. Naji (2012), for example, in her research with women in the Sirwa, identified patterns of men seeking arranged marriages with rural Berber women because of the “morality” associated with what they perceive as “traditional” life and relative confinement and a romantic attraction to a “morally unspoiled” rural world, as opposed to a vision of urban modernity where changing female roles and practices are seen as threatening men’s sense of identity.

In addition to the gendered burden that the feminization of Tamazight cultural and linguistic transmission places on Amazigh women, I also argue that the feminization of the language itself, which links Tamazight authenticity to monolingual women and rurality, is ultimately harmful to efforts to revitalize and regenerate Tamazight language varieties in contemporary Morocco. Although linking Tamazight to rural women should not be seen as intrinsically devaluing the language or culture, contemporary imaginings which mean that the Tamazight language indexes rurality and tradition, which in turn indexes female gender, complicate our ability to imagine Tamazight as an urban, contemporary language, which is essential to any language revitalization effort. Current stereotypes that designate Tamazight as the language of women and the countryside denigrate its use outside of these contexts, for example in the political and public spheres. This is especially dangerous in Morocco, where Tamazight has been presented as an oral language without a capacity to be written and as a relic from the past rather than a language of the future, which is a strategy that jeopardizes its future survival.

I also argue that popular culture celebrating rural women’s role as guardians of heritage and language, along with scholarship that has attempted to unearth Amazigh women’s agency in their contribution to cultural and linguistic transmission, tend to overlook the evolving role of urban Amazigh women. Amazigh women play important roles in urban spaces, including the political sphere, where they not only advocate for women’s rights but also proudly embrace their Amazigh identity. One such example is Soussi Amazigh actress and singer-songwriter Fatima Tabaamrant, who in 2011 decided to enter politics and run in the legislative elections. Inspired by the official recognition of Tamazight in the 2011 Constitution, she made the decision to enter politics, stating that she saw “no contradiction between politics and art in its noble sense,” further highlighting the inseparable relationship between Amazigh music and politics (interview with Fatima Tabaamrant by News Agency Map). Tabaamrant succeeded in winning a seat in the parliament, describing her mission of defending Amazigh women, language, and culture. In April 2012, she created a controversy after voicing a question in Tamazight for the first time in the history of the parliament. In the years since the official recognition of Tamazight, many women-led Amazigh associations have emerged with the specific objective of advancing the voices of Amazigh women. A notable example is the Voice of the Amazigh Woman, a pioneering organization that aims to raise Amazigh women’s consciousness about their rights to education and social justice. On their website they state:

We are the first organization to specifically target the vindication of the rights of women who are Amazigh. We are founded by Amazigh women from across Morocco and we are run exclusively by Amazigh women. We seek to educate Amazigh women of their rights as they may participate fully in society as equals to men and to non-Amazigh Moroccans.[12]

Scholarship that focuses on unearthing Amazigh women’s agency in their preservation of the Tamazight language and (re)production of culture and traditional art forms, as well as popular culture that celebrates Amazigh women for their roles as guardians of tradition and culture, can inadvertently perpetuate stereotypes around Amazigh women, creating a homogenous vision of the Amazigh woman as a rural, folklorized subject who is confined to the rural homeland, overlooking Amazigh women’s roles in politics and civil society and as entrepreneurs and changemakers in contemporary Moroccan society. Although the emerging role of urban, multilingual, educated Amazigh women in the transmission of Tamazight language and Amazigh culture has yet to be studied in depth, Madeleine Spaulding (2023) conducted a small-scale study with urban, educated Amazigh women in Al Hoceima concerning their role in the preservation of Tarifit and Amazigh identity. She found that educated Amazigh women framed their Amazigh identity within the transnational Amazigh movement and concepts of indigeneity and were employing their education and literacy to promote the Tarifit language. Her participants engaged with material related to Amazigh culture and heritage on social media, sent texts and emailed in Tarifit, and saw writing about their culture in Tarifit as an important way of promoting their heritage. Vitally, the written word and social media were being used as tools of revitalization and production, rather than purely of preservation. The myriad ways that urban, educated, literate Amazigh women are exercising their agency within the frameworks of Amazighité and contributing to transnational Amazigh consciousness are not represented by current scholarship or by popular culture which continues to depict Amazigh women as rural and illiterate.

Contemporary revitalization efforts in Tamazgha: achieving the balance

While women have been the linchpins of Amazigh linguistic and cultural preservation and revitalization efforts, Amazigh men have, ironically, figured more prominently in the Amazigh Cultural Movement for valorizing and preserving the Tamazight language (Demnati 2001). Movement leaders are often college-educated male urbanites (Gagliardi, 2018) and the majority of IRCAM researchers are men.[13] In recent decades, for example, Amazigh oral tales and songs, long deemed trivial and unimportant, have become part of a newly appreciated collective heritage, and amateur folklorists have worked to collect and print this literature. These researchers are mostly men, although their informants are often rural women. This is one example of how women’s role in the perpetuation of Amazigh cultural heritage risks being appropriated by the new (often male, urban) culture brokers. As Hoffman (2006) warned nearly twenty years ago, it is unclear whether the individuals most closely associated with formerly devalued Amazigh culture—rural women—will benefit from this new pride in Amazigh contributions to Moroccan heritage. On the national level, it is urban and primarily male intellectuals who design Amazigh language policy and who often make idealized reference to women’s purity or centrality in Amazigh culture and society, further perpetuating the feminized association between Amazigh and rurality.

Recent efforts to standardize Tamazight orthography, promote the use of the IRCAM-fashioned tifinagh alphabet, and integrate Tamazight into the public sphere, for example through teaching standardized Tamazight in schools, have brought the Tamazight language into the conventionally “male domain.” However, the standardization of regional varieties into a single national form as a core component of Tamazight revival efforts, including the writing of Tamazight in the Tifinagh script, may further marginalize and dismiss rural women’s participation in language maintenance. The majority of Imazighen, even those educated in urban spaces, cannot read and write Tifinagh and do not speak the standardized IRCAM version of Tamazight. Dorian (1980) writes that standardization, rather than leading to pride among native speakers, can amplify latent insecurity and shame, as speakers may once again see their own way of speaking as deficient relative to the newly standardized form. Kabel (2018) has argued that the standardization of Tamazight and its introduction into the school system may in fact be contributing to the language’s “devitalization.” Devitalization emerges “at the intersection of colonial histories, state policy, institutionalized language hierarchies, language planning designs and effects, cultural politics, and the structures of linguistic feelings” (Kabel 2018). He argues that principles of authenticity relating to actual language practices were discarded in this standardization process and that this sterilized version of Tamazight risks creating new dimensions of diglossia between illiterate and literate Imazighen, which will particularly impact illiterate Amazigh women. Although standardization efforts may exclude rural populations, in particular women, there is also a case for the symbolic value of the creation of a standardized language and the introduction of Tifinagh in public spaces.[14]

Although current efforts, which have mainly been led by the male urban educated elite, have expanded the horizons of possibility for Tamazight as a written language of everyday life, they have simultaneously displaced rural women from their role as custodians of traditional knowledge, marginalizing those who have maintained Amazigh heritage and transferring linguistic and cultural currency into the hands of educated male intellectuals and policymakers. This has created a disconnect between Amazigh leaders’ vision and the reality of masses of mostly rural and often illiterate Amazigh speakers (Crawford 2002), which risks creating a movement that is not representative of Morocco’s Amazigh people, but also one that risks erasing women's contribution to the survival of Amazigh culture and language.

Ultimately, an approach that feminizes the Tamazight language and Amazigh culture as one of rural, monolingual women and one that transfers all cultural currency into the hands of the urban (often male) elite are both ultimately harmful. In order to ensure the survival of Tamazight in Morocco, we must move away from stereotyping Tamazight as a language solely of rural, monolingual women, particularly in popular culture, but also from marginalizing rural women from revitalization efforts and restricting Tamazight language revival to being a movement of the educated elite. We must instead create new possibilities that place Tamazight at the center of contemporary Moroccan life: possibilities valorizing the integral role that Amazigh women play in its survival and revitalization, but also ones that demonstrate that Tamazight is a language like all others, a language of urban and educated life as well as of the rural homeland, a language of the present as well as the future.

Within the academic sphere, there is a need for greater nuance in studies concerning Amazigh women. Although scholars have started to move beyond depicting Amazigh women as illiterate victims of underdevelopment who lack agency, international development programs largely have not. In addition, in our scholarly efforts to center Amazigh women’s agency, we must guard against focusing solely on Amazigh women’s agency through rural women’s contributions to language preservation and cultural reproduction through traditional crafts and art forms. Although women’s contribution to linguistic and cultural preservation should not be underestimated, this narrow approach to studying Amazigh women’s agency overlooks other sites of agency and also contributes to the continued feminization of the language and culture and the resulting gendered burden faced by Amazigh women. These approaches may also inadvertently promote stereotypes around Amazigh women as solely rural, illiterate subjects engaged in traditional crafts, ignoring important and growing contributions made by highly educated, urban Amazigh women, both within Morocco’s urban spaces and the Amazigh diaspora in Europe and the USA. Avenues for further study include sites of Indigenous women’s agency in Morocco beyond cultural and linguistic preservation, urban Amazigh women’s contributions to the transnational Amazigh movement, and new forms of popular culture enabled by social media such as vlogs, Instagram, and YouTube that challenge gendered stereotypes around Amazigh women.

References

Al-Bakri. c. 1040–1094. Kitab al-Mughrib fi dhikr bilad Ifriqiyah wa-al-Maghrib in Kitab al-mamalik wa-al-masalik.

Al-Idrisi. 1100–1165. Kitāb nuzhat al-mushtāq fī ikhtirāq al-āfāq.

Amazigh World News. Report: Situation of Amazigh Languages in Tamazgha North Africa. June 25, 2019.

Badra, M. 2023. المرأة الامازيغية “تمغارت وورغ” رمز الهوية ومثال العطاء والتضحية. Agadir24.

Bassiouney, R. 2009. Arabic Sociolinguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Becker, S. 2006. Amazigh Arts in Morocco: Women Shaping Berber Identity. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Boukous, A. 2012. Revitalisation de l’amazighe. Défis, enjeux et stratégies. Rabat: Publications de l’IRCAM.

___________. 2013. “L’officialisation de l’amazighe Enjeux et stratégies.” ⴰⵙⵉⵏⴰⴳ Asinag, 8.

Brett, M., and E. Fentress. 1996. The Berbers. Oxford: Blackwell.

Castellino, J. and K. Cavanaugh. 2013. Minority Rights in the Middle East. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Claudot-Hawad, H. 2005. “Les tifinagh comme écriture du détournement.” Études et Documents Berbères 23(1).

Comins-Mingol, C. and B. Laghssais. 2023. “Beyond Vulnerability and Adversities: Amazigh Women’s Agency and Empowerment in Morocco.” Journal of North African Studies 28(2):347-367.

Crawford, D. 2002. “Morocco's invisible Imazighen.” The Journal of North African Studies 7(1):53-70.

___________. 2007. “Making Imazighen: Rural Berber Women, Household Organization, and the Production of Free Men.” In North African Mosaic: A Cultural Reappraisal of Ethnic and Religious Minorities, N. Boudraa, and J. Krause, eds. . ????: Cambridge Scholars Publishing).

Demnati, M. 2001. La femme Amazighe doublement piégée. Available at http://tawiza.byethost10.com/Tawiza60/Demnati.htm?i=1.

Dorian, N. 1980. “Language Shift in Community and Individual: The Phenomenon of the Laggard Semi-Speaker.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 25:85-94.

Elaissi, H. 2015. The Rise of Feminist Consciousness in Morocco: A Study of the Moroccan Feminine/Feminist Discourse. PhD Dissertation. University of Mohammed V, Rabat.

El Guabli, B. 2023. “Translation and Indigeneity—Amazigh Culture from Treason to Revitalization.” The Markaz Review, 14 August 2023 https://themarkaz.org/translation-and-indigeneity-amazigh-culture-from-treason-to-revitalization/

____________. 2023. “The Idea of Tamazgha: Current Articulations and Scholarly Potential.” Tamazgha Studies Journal 1(1):7-22.

____________. 2020. “(Re)Invention of Tradition, Subversive Memory, and Morocco’s Re-Amazighization: From Erasure of Imazighen to the Performance of Tifinagh in Public Life.” Expressions Maghrebines 19(1):143-168.

____________. 2024. “Musicalizing Indigeneity: Tazenzart as a Locus for Amazigh Indigenous Consciousness.” Tamazgha Studies Journal 2(1).

El Khatir, A. 2005. Nationalisme et construction culturelle de la nation au Maroc: Processus et réactions. Doctoral thesis. Paris: EHESS.

____________. 2006. “Etre berbère ou Amazigh dans le Maroc modern : histoire d'une connotation négative,” in Claudot-Hawad, H. (2006) Berbères ou arabes? Le tango des spécialistes. Paris: Éditions Non lieu ; Aix-en-Provence: IREMAM.

El Younssi, A. 2023. The Material Resurgence of Tamazight in the Moroccan Public Sphere: Possibilities and Limits. Tamazgha Journal 1(1).

Fishman, J.A. 1991. Reversing language shift. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual.

Gagliardi, S. 2018. When the ‘Minority’ Speaks: Voices of Amazigh Women in Morocco. PhD thesis, National University of Ireland, Galway.

____________. 2019. Indigenous peoples’ rights in Morocco: subaltern narratives by Amazigh women. The International Journal of Human Rights. 23:1.

Grin, F. 1990. The economic approach to minority languages. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 11(1), 153-73.

Guerch, K. 2015. Moroccan rural Amazigh women: The oppressed of the oppressed. Paper presented at the First International Conference of Translation, Ideology, and Gender in Cantabria University, Santander Spain, November 4-6, 2015.

Hoffman, K. 2002. “Generational Change in Berber Women’s Song of the Anti-Atlas Mountains, Morocco.” Ethnomusicology 46(3):510-540.

____________. 2002. “Moving and Dwelling: Building the Moroccan Ashelhi Homeland.” American Ethnologist 29(4):928–962.

____________. 2006. “Berber Language Ideologies, Maintenance, and Contraction: Gendered Variation in the Indigenous Margins of Morocco.” Language & Communication 26(2):144-167.

____________. 2008. We Share Walls: Language, Land and Gender in Berber Morocco. Oxford: Blackwell.

____________. 2010. “Berber Law by French Means: Customary Courts in the Moroccan Hinterlands, 1930–1956.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 52(4):851–880.

____________. 2010. “Internal Fractures in the Berber-Arab Distinction: from Colonial Practice to Post-National Preoccupations.” In Berbers and others: Beyond tribe and nation in the Maghrib, K. E. Hoffman and S. G. Miller, eds., 39-61. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Hoffman, K., and S. G. Miler. 2010. Berbers and Others: Beyond Tribe and Nation in the Maghrib. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) Kitāb al-‘ibar.

Kabel, A. 2018. “Reclaiming Amazigh in a time of devitalization.” In The Routledge Handbook of Language Revitalization, Hinton L., Huss L., and G. Roche, 485-494. New York: Routledge.

Karrouche, N. 2017. “National Narratives and the Invention of Ethnic Identities: Revisiting Cultural Memory and the Decolonized State in Morocco.” In Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education, M. Carretero, S. Berger and M. Grever, eds., 295-310. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lafkioui, Mena B. 2018. “Berber languages and linguistics.” Oxford Bibliographies Online..

Laghssais, B. 2023. Amazigh Feminism Narratives: Aspirations, Agency, and Empowerment of Amazigh Women in the Southeast of Morocco. PhD thesis at Universitat Jaume I.

Lorcin, P. M. E. 1995. Imperial Identities: Stereotyping, Prejudice and Race in Colonial Algeria. London: I.B. Tauris.

Maddy-Weitzman, B. 2011. The Berber Identity Movement and the Challenge to North African States. Austin: University of Texas Press.

McDougall, J. 2003. “Myth and counter-myth: “The Berber” as national signifier in Algerian historiographies.” Radical History Review 86:66-88.

____________. 2010. “Histories of heresy and salvation: Arabs, Berbers, community and the state.” In Berbers and others: Beyond tribe and nation in the Maghrib, K. E. Hoffman and S. G. Miller, eds., 15-39. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Naji, Myriem. 2012. “Learning to Weave the Threads of Honor: Understanding the Value of Female Schooling in Southern Morocco.” Anthropology and Education 43(4):372-384.

Nettle, D., and R. Romaine. 2000. Vanishing Voices: The Extinction of the World’s Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Oubenal M. 2019. Les défis de la musique urbaine amazighe : Le cas des artistes d’Agadir, in : Aboulkacem et al., Les expressions musicales en milieux amazighes, Rabat, IRCAM.

Sadiqi, F. 2007. “The Role of Moroccan Women in Preserving Amazigh Language and Culture.” Museum International 59(4):26-33.

____________. 2003. Women, Gender and Language in Morocco. Leiden: Brill.

____________. 2014. “The Big Absent in the Moroccan Feminist Movement: the Berber Dimension.” Studi Magrebini Nuova Serie 14:2.

Silverstein, P. 2002. “France’s Mare Nostrum: colonial and post‐colonial constructions of the French Mediterranean.” The Journal of North African Studies 7(4):1-22.

____________. 2023. “The Productive Plurality of Tamazgha: Boundaries, Intersections, Frictions.” Tamazgha Studies Journal 1(1):23-34.

Spaulding, M. 2023. Language as a Bridge to the Soul: The Role of the Urban, Multilingual, Literate Amazigh Woman and Tarififit in Preserving Amazigh Ethnic Identity in the Rif. Channels: Where Disciplines Meet 8(1):1-39.

Tilmatine, M. and Y. Suleiman. 1999. “Language and Identity: The Case of Berber.” In Language and Society in the Middle East and North Africa (165-180), Y. Suleiman, ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

Wyrtzen, J. 2011. “Colonial state-building and the negotiation of Arab and Berber identity in Protectorate Morocco.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 43(2):227-249.

Yassine, T. 2001. “Women, their Space, and Creativity in Berber Society.” Race, Gender, and Class 8 (3):102-113.

Zartman, I. W. 1964. Government and politics in Northern Africa. London: Methuen

Footnotes

[1] Tamazgha serves as an imagined community (in Anderson’s sense) for Imazighen and represents an imagined, pan-Amazigh homeland extending from the Canary Islands in the West to the Siwa Oasis of Egypt in the East. Tamazgha represents both a shared past and common memory, but also sets the scene for a common future. Transcending national borders imposed by colonial powers, Tamazgha represents a transnational Amazigh identity and challenges hegemonic representations of North Africa as an Arabo-Islamic region. For more on the articulations and possibilities of Tamazgha, see El Guabli (2023) and Silverstein (2023).

[2] Although not a minority language due to the sheer proportion of native speakers, Tamazight can be better described as a “minoritized” rather than minority language. Tamazight language varieties share some of the characteristics of a minority language, including marginalization and attempts to devalue the language or present it as archaic and not useful. I therefore find that studies around minority languages and their revitalization can be useful in the context of Amazigh languages. Boukous (2013; 2012) has argued that Tamazight in Morocco has suffered to such an extent from official marginalization that it has become a minority language. Likewise, Gagliardi (2019) argues that although Imazighen constitute Morocco’s largest ethnolinguistic group, they are best categorized as a “majoritarian minority” (see Castellino and Cavanaugh 2013). Minority status is not solely defined by the relative size of a particular community, but by cultural and political factors and a group's engagement with, or exclusion from, sites of power.

[3] Tanit was the Amazigh goddess of prosperity, fertility, love and the moon.

[4] Dihya was born in the early seventh century in the Aures Mountains in Algeria. According to Ibn Khaldun in Elaissi (2015), “among their most powerful leaders, we noticed especially the Kahena, queen of Mount Auras, whose real name was Dihya, daughter of Tabeta, son of Tifan. His family was part of the Djeraoua, a tribute which provided kings and chiefs to all the Berbers descended from El-Abter.” She is also known in Arabic by the name of El Kahina, meaning prophetess, seer, or witch, a title given to her by Muslim opponents because of her alleged ability to foresee the future. Warrior queen Dihya played a significant role in defending her kingdom and leading the North African resistance against the early Arab-Islamic conquests of the Maghreb, the region known then as Numidia (Laghssais and Comins-Mingol 2023).

[5] Tin Hinan, or Tamnugalt, played a leading role in the protection of the Tuareg tribes as she was revered and respected as a symbol of social, political, and spiritual balance and stability. The Tuareg tribes considered her to be their spiritual mother and thus they understand the name Tin Hinan to mean “mother of the tribe” or “queen of the camp.”

[6] Ibn Battuta (d.1377), Tuhfat an-nuzzar fi ghara’ib al-amsar wa ‘aja’ib asfar, quoted in Mohammed Badra (2023), المرأة الامازيغية “تمغارت وورغ” رمز الهوية ومثال العطاء والتضحية, Agadir24.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Al-Bakri (c. 1040–1094), Kitab al-Mughrib fi dhikr bilad Ifriqiyah wa-al-Maghrib in Kitab al-mamalik wa-al-masalik, Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) Kitab al-ibar, Muhammad al-Idrisi (1100–1165), Kitāb nuzhat al-mushtāq fī ikhtirāq al-āfāq as referenced in Mohammed Badra (2023).

[9] For more examples of early Amazigh women poets, see Sadiqi (2014).

[10] Thanks to Ahmed Abaamrane for his time and collaboration in discussing the project behind this song.

[11] For more on tamazirt and the gendered dynamics of rural vs. urban dwelling, see Hoffman (2002).

[12] See, https://imsli.org.ma/new/.

[13] One notable exception is Fatima Agnaou, who oversaw the development of Tamazight language textbooks for introduction in schools.

[14] For a more in-depth discussion on the introduction of Tifinagh in Morocco’s public spaces, see El Guabli (2020), El Younssi (2023), and Claudot-Hawad (2008).

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 3 • Issue 1 • Spring 2025

Pages 53-69

Language: English

INSTITUTION

University of Oxford