Translatability of Tamazight songs into English: A Case study: Famous Songs by the Moroccan Singer Mohamed Rouicha

AUTHOR: Abdessamad Binaoui and Mohammed Moubtassime

Peer Reviewed Article

Translatability of Tamazight songs into English:

A Case study: Famous Songs by the Moroccan Singer Mohamed Rouicha

Abdessamad Binaoui and Mohammed Moubtassime

Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University

Abstract: This study delves into the various techniques and procedures that could potentially be used in translating songs from Tamazight into English. The corpus for this study comprises translations of two famous songs by the renowned Moroccan singer and composer Mohamed Rouicha, whose artistic genre had a great influence on Moroccan as well as non-Moroccan audiences. In this article, we have addressed the translation of Rouicha’s songs in order to allow foreign readers to understand them and capture their beauty. Also, we hope that other translators will use the findings of the present study as a guide for future translations from Tamazight into English. The process of translating between Tamazight and English involves navigating a multitude of linguistic and cultural intricacies resulting from the grammatical differences between the two languages. While Tamazight often omits personal pronouns, English may require their addition for clarity. Moreover, the translator of Tamazight must possess a deep understanding of the cultural context to accurately convey nuanced meanings. Sometimes a literal translation suffices, but most often careful consideration is required, especially when it comes to metaphors, which can be particularly challenging. Structural differences, such as the sentence formation pattern and the usage of active and passive voices, also demand attention. Furthermore, the discrepancy in collocations often necessitates adaptation. In cases where cultural disparities are significant, explanations may be needed to ensure comprehension. Through techniques like modulation and transposition, translators strive to bridge these linguistic and cultural gaps effectively.

Keywords: Tamazight, English, Rouicha, Songs, Translation.

Introduction:

Amazigh culture, like most of its counterparts, has a significant heritage that includes traditions, lifestyle, types of dresses, celebration rituals, language preferences, and social conventions, to name a few. The Tamazight language is, accordingly, full of cultural and linguistic items that are very meaningful to native speakers but present challenges when the meaning is to be conveyed into other languages. Tamazight possesses emphasis-oriented structures, crucial in terms of conveying accurate meaning. As a result, the translation process and its outcome are worth investigating.

Amazigh songs are vehicles of Imazighen’s emotions, thoughts, and hopes. People interested in the study of Amazigh culture will find it worthwhile to inquire into the meanings of these songs. Yet translating Amazigh songs poses many challenges since Tamazight has a rich corpus of culture-specific items; therefore, it is necessary to identify the problems the translator encounters and suggest solutions to make the process smoother. Drawing on the songs of the famous artist Mohamed Rouicha, this article engages in these two processes to model a translation of songs from Tamazight into English. However, it is worth noting that despite our best efforts, the rhymes and the meters are sacrificed for the sake of maintaining accuracy. Although Rouicha’s musical legacy is very rich, this study only uses two of his songs.

The article provides the translation of two songs, “Inas Inas” and “Idda Zman,” followed by a reflection on the translation process. Mohamed Houari (1950–2012), mostly known by his stage name Mohamed Rouicha, was a Moroccan singer (both in Tamazight and Darija). His songs revolve around daily life and love, but his most famous songs are “Idda Zman” and “Inas Inas,” which have become iconic sounds in the Moroccan soundscapes.

This study is based on a descriptive model of translation (DTS). According to Theo Hermans (1999, as cited by the University of the Witwatersrand, n.d.), the descriptive and systemic approach to translation began in the 1960s and 1970s, gained popularity in the 1980s, and was refined in the 1990s. This approach was introduced to the broader academic community in 1985 as “a new paradigm” in translation studies (Hermans, 1999). Hermans notes that the descriptive model of translation integrates three general functions of language with three levels of narratological analysis. He attributes these functions to Halliday (1989, as cited by the University of the Witwatersrand, n.d.), asserting that they are inherent to all linguistic expressions, including narrative texts. The first function, termed the “interpersonal function,” refers to how communication between the speaker and listener is established (Halliday, 1989 in Hermans 1999: 60). The second, the “ideational function,” pertains to how information about the fictional world is conveyed, shaping the image presented to the reader (Hermans, as cited by the University of the Witwatersrand, n.d.). The third function, the “textual function,” relates to how information is structured and organized in language (Hermans 1999, as cited by the University of the Witwatersrand, n.d.). In this study, we will focus on the descriptive aspect of the translation techniques used to convey the original meaning of Tamazight into English. We seek to answer several questions, including the nature of the problems the translator encounters in translating Tamazight songs into English, whether Amazigh words and expressions are translatable into English, whether it is preferable to use a domesticating or foreignizing approach or a combination thereof, and the extent to which English translations convey the original meaning in Tamazight. This article is guided by the premise that there are ample difficulties in translating some words and expressions, especially culture-specific items, and that domestication (as well as modulation, adaptation, and transposition) will probably be mostly appropriate for this kind of translation. Accordingly, some expressions could be untranslatable. Finally, a communicative translation of the source text will also be used since we are dealing with texts that possess a poetic function.

Analysis of data will involve identifying all the problems encountered in translating and the preferable translation methods and techniques used to deal with each category. Finally, we will suggest some solutions associated with each category. The analysis will be mainly qualitative. In other words, it will consist of commenting on the strategies and techniques used in translating the culture-specific items by examining some samples excerpted from the translated songs. More precisely, the focus will not only be on the translator’s choice of strategies and techniques, but also on the grammatical and structural conventions on which meaning heavily depends.

Amazigh Language and Culture

Imazighen (Amazigh people), mostly known in the literature as Berbers, are the Indigenous inhabitants of North Africa. Imazighen have had a continuous presence in Tamazgha as the Indigenous populations of the area since antiquity (as El Aissati, 2005:59). El Aissati (2005:60) has identified the borders of the land of Imazighen, which covers the area between the Siwa oasis near the Egyptian and Libyan borders to the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean and from the southern coast of the Mediterranean to the Northern areas of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Amazigh activists have named this area Tamazgha (see the Tamazgha Studies issue on Tamazgha). While this territory is traversed by different Amazigh languages and cultures, this article focuses on the Middle Atlas in Morocco and the variation of spoken Tamazight in which Rouicha’s songs were composed.

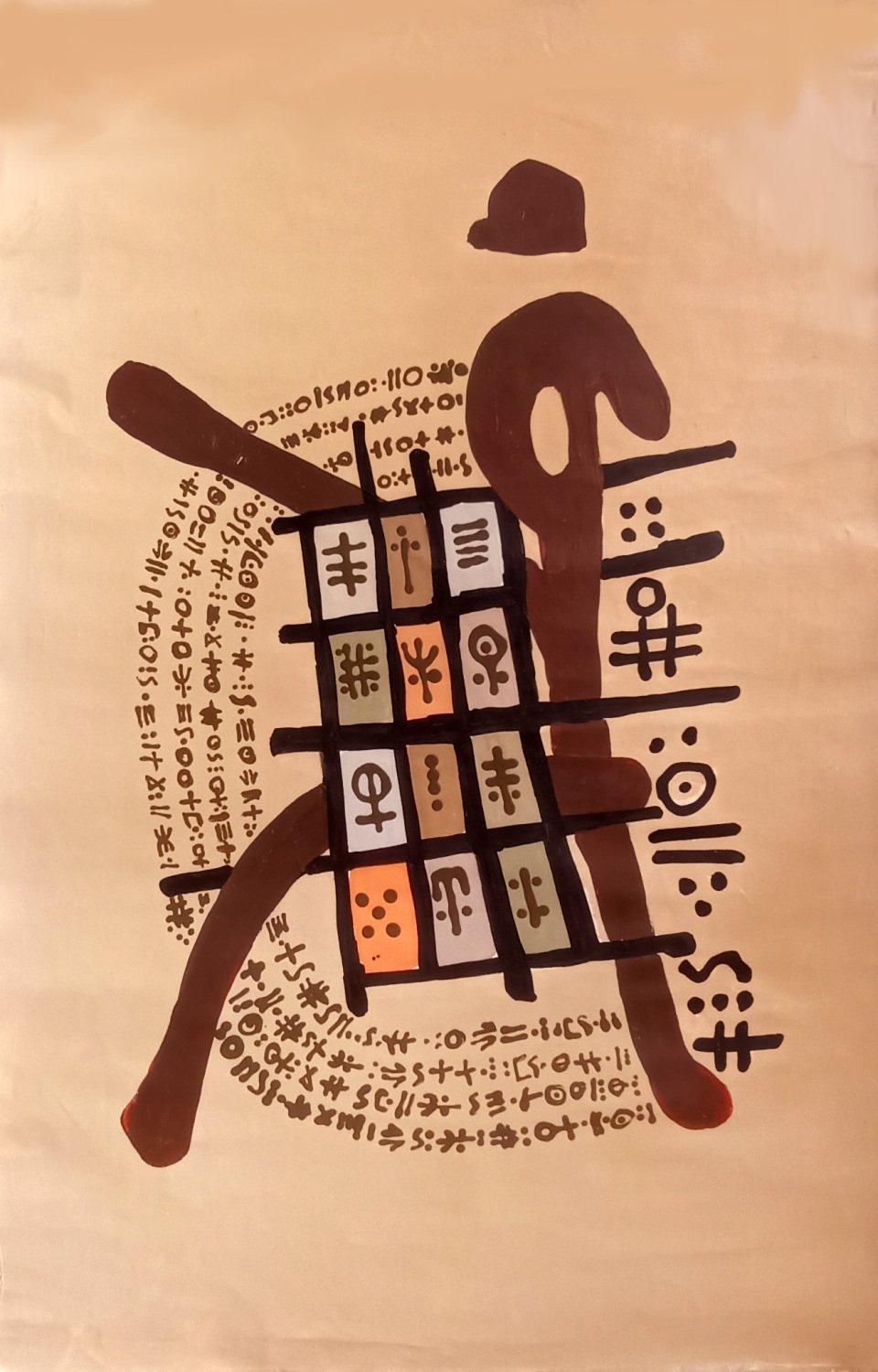

Even though there is a very rich Amazigh heritage and Amazigh language and culture are of the indigenous people of North Africa, they have been marginalized for decadesdespite Imazighen’s sacrifices in their fight and resistance against French and Spanish colonization. This marginalization led to the emergence of a community of activists known as the Amazigh Cultural Movement, which engaged in debates and demonstrations to call for the recognition of their integral identity within Moroccan culture. The recognition of the Amazigh language as a constitutional language alongside Arabic was one of the movement’s important demands. The situation of Tamazight improved significantly in 2001 when King Mohamed VI, in a speech he gave in Ajdir, announced the creation of the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture in Morocco (RIACM or IRCAM in French). The Institute provides consultations on measures aimed at safeguarding and promoting Amazigh culture in all its expressions at the national, regional, and local levels. It collaborates with relevant institutions to strengthen Morocco’s cultural diplomacy by highlighting the Moroccan model of managing cultural and linguistic diversity,to implement policies that facilitate the introduction of Amazigh into the educational system and to ensure its visibility in the social, cultural, and media spheres (Institut Royal de La Culture Amazighe | Missions de l’IRCAM) The task of institutionalizing the teaching of Tamazight was not easy due to its oral nature and its multiple variations. The same language is called Tashlihit in the Suss, Tamazight in the Middle Atlas, and Tarifit in northeastern Morocco. El Aissati (2005:61) notes that the Amazigh language has been classified as a descendant of the Afro-Asiatic branch, which includes Semitic languages, Ancient Egyptian and its “descendant” Modern Coptic, the Kushitic language, etc. The language is written in an old alphabet called Tifinagh, which, according to Chaker (2004) has “enabled Berbers to no longer be characterized among barbarians and other undermining labels”, indicating that being able to write a language gives it a tangible existence. It thereby enjoys a stronger status than if it were to have remained oral. IRCAM has adopted the solution of forging a common language by deriving vocabularies and structures of these variations and by adopting the standardized Tifinagh script. IRCAM has also published pedagogical and lexical materials that are needed for teaching and conducting academic research in Tamazight.

Translation and its Genre-specific Questions

Translation of poetry and songs

It is often believed that each text type requires a certain type of translation in terms of procedures and techniques that reflect the same text functions, etc. In the case of song translations, the target text must render the aesthetic value of the source text as Low (2005:185) suggests: rhythms, note values, harmonies, durations, phrasings, and stresses are examples of features within music that cannot be ignored when translating lyrics. The target text should be in the form of a song, with alliterations, rhymes, and chorus. As demonstrated by Low (2005:190), the song must be singable, and the text must sound as if it had been made for the music. The cultural dimension of the target audience must be taken into consideration so as to be culturally sensitive and to avoid conveying meaningless target texts. Eco (2001:17) argued that a translator should account for rules that extend beyond language and that encompass broader cultural factors. Eco’s statement highlights that translation goes beyond simply converting words and grammatical structures from one language to another; it involves a deep understanding of cultural context.

Translation of Culture-specific Items

Culture-specific items or culture-bound terms are items that can be spotted in their proper culture. Palumbo (2009) suggested that various techniques are employed for the translation of such elements, depending on whether the audience is already familiar with the term or concept, or if there exists the possibility of finding functional equivalents in the target language (TL), that is, terms that refer to analogous concepts in the TL culture. The borrowing of terms like “Weltanschauung” from German or “samovar,” which is transliterated from Russian, are examples of this practice discussed by Palumbo. Others are translated by means of a calque, such as “Prime Minister” (English) and “Primo Ministro” (Italian). In other cases, a functional equivalent may be provided, as in the case of “Abitur” in German for “A-levels” in British English, or the SL (source language) item may be retained and a short explanation added, e.g. the Daily Telegraph translated into Italian as El quotidiano (where “quotidiano” is a “daily newspaper”). In Tamazight-English translation, similar techniques can be used to address terms that lack direct equivalents or carry distinct cultural meanings. For instance, a calque, translating a term literally, may be used when Tamazight and English concepts align closely. If a specific political or administrative title in Tamazight has a straightforward English equivalent, like "Prime Minister," it can be translated literally to ensure clarity for English-speaking readers. In cases where concepts are culturally specific to Tamazight-speaking regions and lack a direct English equivalent, translators might use a functional equivalent, adapting the term to something similar in English that captures its purpose. Alternatively, for uniquely Tamazight items, translators might retain the original term and add a brief explanation in English. This approach balances fidelity to Tamazight culture while providing clarity, allowing readers to understand culturally unique references without losing their original significance.

Palumbo suggested that strategies, such as domestication (see next paragraph for definition), can be used to deal with such items where equivalent items are used in the target culture to render the same effect of the translation at the same time as making the text more accessible to the target audience. In contrast to this technique, using foreignization means keeping the foreignness of these items and thus transliterating them or perhaps explaining them between parentheses.

Translation studies scholars have distinguished between two distinct procedures in translation: domestication and foreignization. These two translation strategies provide both linguistic and cultural guidance (Yang, 2010). Domestication, according to Palumbo (2009: 38), entails translating in a transparent form felt as capable of giving access to the source text author’s precise meaning, which is a definition derived from Lawrence Venuti who has analyzed this concept thoroughly. At the other extreme, Palumbo (2009:48) suggests that foreignization refers to a translation strategy aimed at rendering the source text conspicuous in the target text or, in other words, at avoiding the fluency that would mask its being a translation. According to Palumbo (2009,48), the term is mostly associated with the name of Lawrence Venuti, who sees TL (target language) fluency as a prevailing ideal that suppresses the otherness of the source text and minimizes the role of the translator. Foreignizing translation is thus seen by Venuti as a form of resistant translation opposing the prevailing ethnocentric modes of transfer.

The two concepts of domestication and foreignization must be seen as showing contingent variability, meaning that their definition always depends on the specific historical and cultural situation in which a translation is made (Venuti 2008). Venuti (1995) suggests that a translator could choose the now-traditional domesticating method, an ethnocentric reduction of the foreign text to dominant cultural values in English; or a translator could choose a foreignizing method, which exerts an ethnic-deviant pressure on those values to register the linguistic and cultural differences of the foreign text, as a way of favoring foreignization over domestication, given that he considers domestication as a falsification of the source text culture (Venuti, 1988:242). Regardless of the translator’s choices or the requirements of the target audience, and of whether a foreignizing approach is used to ensure cultural understanding while translating culture-specific items, cultural factors are among the major issues which dominate the process of translation, (Venuti 1988).

In Tamazight-English translation, domestication is favored over foreignization, as it adapts cultural references and idioms into familiar terms for English-speaking audiences, thereby reducing cultural distance. While foreignization is selectively used to preserve unique Tamazight expressions, domestication offers a smoother reading experience and addresses the complexities of translating Tamazight’s linguistic features into English.

Translation of metaphors

In translating Amazigh songs, particularly those by Mohammed Rouicha, the metaphor presents distinct challenges due to its central role in conveying deep cultural meanings. Shuttleworth (2011) notes the similarity in etymology for both metaphor and translation, as both involve a “transfer” of meaning; translation carries content across languages, while metaphor shifts understanding within a single language in a rich, eloquent way. Newmark (1985) classifies techniques for translating metaphors to help maintain this depth, such as reproducing the same image in the target language (TL), using culturally equivalent images, converting metaphors into similes, or adding explanatory notes. These approaches ensure that metaphorical expressions resonate within the TL without losing their original impact. Techniques like modulation, transposition, and adaptation further support this process, allowing translators to adjust perspective and grammar while respecting cultural specificity (Vinay & Darbelnet, 1995; Munday, 2016). Translating Rouicha’s work effectively requires this nuanced handling of metaphor to preserve the emotive and cultural essence of Amazigh songs in English.

First song “Inass Inass”

In this section, the song “Inas Inas” shall be divided into segments, transliterated into the Latin alphabet, translated into English, and analyzed in terms of the techniques and strategies used in order for it to be accurately translated. It must be noted that the repeated segments will not be repeated in the translation.

First segment:

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵉⵏⴰⵙ ⵉⵏⴰⵙ ⵎⴰⵢⵔⵉⵖ ⴰⴷⴰⵙ ⵢⵖ ⵉⵣⵎⴰⵏ |

| Latin transliteration | Inas Inas mayriɣ adas yeɣ izman |

| Literal translation | Tell him tell him what I need to do about the time |

| English translation | Ask my beloved, ask her/him how should I deal with the ups and downs of time. |

In this passage, there was the addition of the phrase “my beloved” for the purposes of clarity because the complement the singer refers to is not yet mentioned. Furthermore, both gender pronouns (him/her) are used due to the fact that most phrases from Amazigh songs can be sung by both genders while referring to each other, especially in love songs. In addition, in the source text, there is an omission of the pronoun “I” because Tamazight tolerates such a phenomenon, as in Spanish (yo escribo=escribo), but the English translation requires the use of the pronoun. Finally, it is worth observing that when translating the last word “izman,” meaning “about time,” there is the addition of “ups and downs” in the target text for the purposes of accuracy because the concept of “zman,” which means “time,” “life,” or “daily struggle” should be more explicit in English.

Second segment:

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵡⵏⵏⴰ ⵓⵔ ⵢⵓⴼⵉⵏ ⵎⴰⵖⴰⵙ ⵉⵛ ⵉⵡⵏⵏⴰ ⴷ ⵉⵜⵎⵓⵏ |

| Latin transliteration | Wnna or yofin maɣas ich iwnna d itmon |

| Literal translation | Who doesn’t find what to give to his companion? |

| English translation | When one cannot find what to offer to his/her beloved |

It can be observed that in the translation of this segment, there was the addition of the temporal conjunction “when,” which doesn‘t figure in the source text. We translated it in such a way for the purpose of explicitness and in order to link it to the previous segment. Moreover, in translating the word “ⵉⵛ” i.e., “give,” the context implies an action of offering rather than an action of giving. Last but not least, the translation of the word “ⵉⵜⵎⵓⵏ” i.e., “companion” was actually translated as “beloved” rather than “companion” because this is its primary connotation.

Third segment:

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵓⵔⴷⴰ ⵉⵙⵏⴰⵇⴰⵙ ⵜⵙⴰⵔⵜ ⵖⴰⵙ ⵊⵉⴱ ⵉⵅⵡⴰⵏ |

| Latin transliteration | Orda isnaqas tsart ɣas jib ikhwan |

| Literal translation | Arrogance is reduced by the empty pocket |

| English translation | Poverty reduces arrogance |

The source text sentence is formed with the order of verb + subject + object; however, it was translated in the typical English order of subject + verb+ object. Tamazight is more like Arabic in its sentence formation. Moreover, the word “tsart” is translated with the nuanced term “arrogance,” which is enforced by the context; if the word was taken out of context, it would mean “pride.” Additionally, the word “ⵊⵉⴱ ⵉⵅⵡⴰⵏ” i.e., “empty pocket” is a metaphor for poverty, which is derived from the context.

Fourth segment:

| Tifinagh transcription | ⴰ ⴷⵓⵏⵉⵜ ⵓⵔⵉ ⵜⵔⵉⴷ ⵡⴰⵍⴰ ⵜⵉⵡⵉⴷⵉ ⴰⵍⵎⵓⵜ |

| Latin transliteration | A donit ori tride wala tiwidi almot |

| Literal translation | Life rejects me nor does death take me |

| English translation | Oh life, you dislike me, and death does not want of me |

In this segment, the singer addresses life directly and bemoans his luck: no love, no life, and not even death are within reach. Thus, this segment explains how love may breed misery. There are differences in punctuation between the source and target texts. The target text also includes the addition of the personal pronoun “you,“ which the source text omits. As previously mentioned, Tamazight often omits personal pronouns since verb conjugations allow them to be inferred.

Fifth segment:

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵏⴽ ⴰ ⵔⴱⴱⵉ ⴰⵢ ⵜⵓⴷⵊⵉⴷ ⵉⵏⵖⵔ ⵓⵏⵔⵖⵉ ⴷ ⵓⵇⵔⴰⴼ |

| Latin transliteration | Nk a rbbi ay todjid inɣr onrɣi d oqraf |

| Literal translation | Me, my God, whom you left between heat and cold |

| English translation | It is me, my God, whom you left to suffer |

The personal pronoun “it” was omitted in the source text while it appears in the target text. Moreover, the singer addresses God and complains in metaphorical terms about how he has suffered due to love, at times left to be burned by its heat and at other times stung by its cold (“between heat and cold”). Ultimately, “heat and cold” was translated as “suffering.”

Sixth segment:

| Tifinagh transcription | ⴰ ⵢⴰⵢⵜⵎⴰ ⴰⵎ ⵏⴽ ⴰⵖ ⵙⵜⴰⵀⵍ ⴰⴷ ⵉⵜⵔⵓ |

| Latin transliteration | A yaytma am nk aɣ stahl ad itro |

| Literal translation | My brothers like me deserve to cry |

| English translation | My brothers, I deserve to cry |

In this segment, the singer addresses his audience as his brothers, complains about his situation, and affirms that he deserves to be crying and suffering. Here again, the literal translation was successful in conveying the meaning. The English sentence This is the rat that lives in the house that Jack built would be rendered in Japanese as this Jack-built-house live-in-rat is (Wallwork, 2017); similarly, sometimes when translating from Tamazight, it is necessary to change the order of the words to form a well-structured sentence.

Seventh segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵉⵙⵉ ⵉⵏⵖⴰ ⵍⵉⵇⵏⴰⴷ ⵉⴱⵄⴷⵉ ⵓⴱⵔⵉⴷ ⵓⵙⵎⵓⵏ |

| Latin transliteration | Isi inɣa liqnad ibεdi obrid osmon |

| Literal translation | I’m hurt by the absence; the road is far from my beloved |

| English translation | I miss my beloved, who lives far away |

In this segment, there is no personal pronoun “I” in the source text. For this segment, literal translation is inadequate; rather, a translation that uses modulation is preferable, with the word “absence” becoming the phrase “I miss.” As Newmark (1988:88) argues, “Modulation occurs when the translator reproduces the message of the original text in the TL text in conformity with the current norms of the TL, since the SL and the TL may appear dissimilar in terms of perspective.” Modulation is also employed with “the road is far,” which is rendered by “who lives far away.” Consequently, for this entire segment, there was a preference for using modulation in the translation process.

Second song: “Idda Zman”

This song is more social than emotional; it is a kind of comparison between life in the past and what it is today and the injustices suffered by the poet’s community. The singer provides examples of war in Palestine and Iraq while also addressing the stress that burdens individuals. It must also be noted that we avoid repetition in order to spare ourselves redundancy, since the aesthetic effect is not targeted here but rather the translation techniques and difficulties.

First segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵎⴰⵜⵜⴰ ⵣⵎⴰⵏ ⵉⵙⵙⴰⴳⴰⵏ ⵉⴷⴷⴰ ⵣⵎⴰⵏ ⵉⵖⵓⴷⴰⵏ |

| Latin transliteration | Matta zman issagan idda zman iɣodan |

| Literal translation | What a time to dislike, the good times are far gone |

| English translation | What an abominable time, the good times are over |

This segment is also the title of the song; the first half is translated by modulation (see reference about modulation: Newmark, 1988b:88) where “matta zman” i.e., “what a time” is translated as “an abominable time.” The second half is translated by transposition where “zman” i.e., “time” is translated as “times.”

Second segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⴰⴷⵊ ⴰⴷⵔⵓⵅ ⵉⵎⵜⵉⴰ ⵍⵓⵇⵜ ⴰⴳⴰⵏ ⴱⵏⵉⴷⴰⵎ |

| Latin transliteration | Adj adrox imeti a loqt agan bnidam |

| Literal translation | Let me cry a tear, this is what time deserves |

| English translation | Let me shed a tear over these hard times |

The first half of the segment was served sufficiently by a literal translation while the second required transposition; however, the English translation entails the use of a verb in this context, i.e., “require” because the word order differs significantly from one language to another. To express a simple sentence such as “I like you,” various languages employ differing constructions: to me you (Croatian), you like to me (Estonian), you are liking to me (Irish), I you like (Korean), to me you like (Spanish), you me I like (Wolof) (Wallwork, 17).

Third segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵡⴰ ⵉⵖⴰ ⵍⵃⴰⵇ ⴰⵎ ⵓⵀⵉⵣⵓⵏ ⵡⴰ ⵢⵉⵡⴷ ⴰⵛⴰⵍ ⵉⵅⵓⴱⴰⵙ |

| Latin transliteration | Wa iɣa lhaq am ohizon, yiwd acal ixobas |

| Literal translation | Righteousness is like a disabled person, when it touches the ground it suffers |

| English translation | Righteousness is disabled, when on Earth |

This segment comprises a metaphor that establishes a connection between what is right in terms of common sense with a person with a disability in the sense that defending what is right or being righteous is hard and can cause suffering in this life (on Earth). This image was translated by converting the metaphor to sense as described by Newmark (1985: 304-311). Therefore, to convey the meaning, “righteousness” simply became disabled rather than being compared to a person with a disability.

Fourth segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⴰ ⵍⴱⴰⵟⵍ ⴰⵡⴰ ⵜⵓⴼⵉⴷ ⵎⴰⵛ ⵉⵜⵀⵣⵣⴰⵏ ⵏⵏⵉⵖⴰⵙ |

| Latin transliteration | A lbatl awa tofid mac ithzzan nniγas |

| Literal translation | Evil you found who lifts you above it |

| English translation | Evil, they made it easier for you to reign over righteousness |

This segment is correlated with the previous one as it addresses “evil” in contrast with “righteousness,” with the metaphor being that evil reigned over righteousness; again, this is translated with the conversion of metaphor into sense (see translation).

Fifth segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵡⴰ ⵎⴰⵙⴰⵅ ⴷⵓⵍⵉⵏ ⵉⵛⵉⴱⴰⵏ ⵉⵍⵍⴰ ⵓⵅⵎⴰⵎ ⴷⵉⵖⵢ |

| Latin transliteration | Wa masax dolin iciban Illa oxemmem diγy |

| Literal translation | How we have been made white-headed; thinking is in me |

| English translation | Overthinking made me grow old fast |

Sixth segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⴰⵜⵢⵔ ⵉⴷⴷⴰ ⵢⵉⵡⵉⵛⵀ ⴰ ⵢⴰⴼⵔⴰⵃ ⵣⵉⵖⵉ |

| Latin transliteration | Atyr idda yiwich a yafrah ziɣi |

| Literal translation | Sadness had taken you away from me, joy |

| English translation | Sadness replaced you, my joy. |

The sixth segment tolerated a literal translation while rendering almost the same structure. However, for the sake of accuracy, especially in the target language, “taken away” was supplanted by “replaced.”

Seventh segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵡⴰ ⴼⵉⵍⵉⵙⵜⵉⵏ ⵉⵅⵓⴱⴰⵙ ⴰⵜⵜⵓⵢⵏⴰⵙ ⵉⵖⵓⴷⴰⵔ |

| Latin transliteration | Wa Filistin ixobas Attoynas iɣodar |

| Literal translation | Palestine suffers its walls are broken down |

| English translation | Palestine is suffering, it is being destroyed |

The seventh segment was translated by meaning transfer. We translated the phrase “broken down” as “it is being destroyed.”

Eighth segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵡⴰ ⵢⴰⴽ ⵉⵔⵓⵍ ⵉⵣⵔⵢⴰⵛ ⴰ ⵢⴰⵄⴷⴰⵡ ⴰⵎⴰⵣⵉⵔ |

| Latin transliteration | Wa yak irol izryac a yaεdaw amazir |

| Literal translation | He runs leaving to you, enemy, his land |

| English translation | Oh, enemy, they fled abandoning their land to you |

In this segment, there is a grammatical change of the personal pronoun from “he” to “they.” This phenomenon is common in Tamazight. When the singer refers to one Palestinian, he is ultimately referring to all Palestinians.

Ninth segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵍⴰⵜⵄⵔⴰⵏ ⵍⴱⵉⴱⴰⵏ ⵉⴱⴱⵉ ⵓⵣⴰⴳⵓ ⵏ ⵡⴰⴷⵊⴰⵔ |

| Latin transliteration | latεran lbiban Ibbi ozago n wadjar |

| Literal translation | They tear down walls, shut are the sounds of neighbors |

| English translation | They tear down walls, neighbors’ voices are shut off |

The first half was translated literally while the second half was modulated from the passive “shut are the sounds of neighbors” to the active “neighbors’ voices are shut off” because Tamazight’s passive voice structure differs from the one in English.

Tenth segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵉⴱⴱⵉ ⵔⵙⴰⵙ ⵉⴱⵔⴷⴰⵏ ⵉⵍⵍⴰ ⵍⵅⵓⴼ ⴳ ⵜⵉⴷⴷⴰⵔ |

| Latin transliteration | Ibbi rsas iberdan Illa lxof g tiddar |

| Literal translation | Bullets cut roads, fear is in houses |

| English translation | Bullets empty roads, fear invades the houses |

The first half of this segment does not tolerate a literal translation because “cut” does not collocate with roads in English in this context. In the second half, the verb “invades” conveys the meaning better than the verb “to be” in the same context.

Eleventh segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⴱⴷⴰⵏ ⵡⵉⵏⵏⴰ ⵉⵎⵃⵓⴱⴱⴰⵏ ⵎⵇⵇⴰⵔ ⵜⵍⵍⴰ ⵍⵄⵣⴰⵣⵉⵜ |

| Latin transliteration | Bdan winna imḥubban Mqqar tlla leεzazit |

| Literal translation | Divided are Lovers although exists love |

| English translation | Lovers are being separated even if they love each other |

Obviously, a literal translation won’t cut it in this segment due to the unmatched structures of the SL and the TL. However, an easy adaptation of the structure to the TL will do for the sake of meaning transfer.

Twelfth segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵡⴰ ⵛⴰ ⵣⵔⵉⵏ ⴰⵢⵜⵎⴰⵙ ⵉⵜⵜⴰⴱ ⵄⵉⵏ ⵉⵍⵖⵔⵓⴱⵉⵜ |

| Latin transliteration | Wa ca zrin aytmas ittab3in ilɣrobit |

| Literal translation | Some left their brothers and followed abroad |

| English translation | Some left their families seeking loneliness abroad |

As can be observed in this segment, there is a shift from “brothers” to “families” because that is the probable meaning derived from the context and from my experience as a native speaker of Tamazight. Furthermore, the word “ilɣrobit” is explained by two words: “loneliness abroad.” It is possible to conclude that sometimes explanation works in this type of translation.

Thirteenth segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵎⴰⵛ ⵉⵙⵇⵡⴰⵏ ⴰ ⵢⵓⴷⴰⵢ ⵉⵍⵍⴰ ⵓⵅⵜⵜⴰⵜ ⵣⵖⵓⵏ |

| Latin transliteration | Mac isqwan a yoday Illa oxttat zeγon |

| Literal translation | What enforced you, Jew, the planners are among you |

| English translation | Your plans enforced you, Jew! |

Fourteenth segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⴰⴷⵊ ⴰⵄⵔⴰⴱ ⴰⴷⵉⵔⵍⵃ ⴷⴰⵜⵏⵇⵇⴰⵏ ⵉⵏⵉⴳⴰⵏ2 |

| Latin transliteration | Adj Aεrab adirlh datnqqan inigan |

| Literal translation | Let the Arab be killed |

| English translation | Have the Arabs killed |

This song communicates a form of sympathy towards Arabs. In this segment’s translation, adaptation was used in order to convey the meaning more accurately.

Fifteenth segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵀⴰ ⵍⵓⴱⵏⴰⵏ ⴱⵏⵉⴷⴰⵅ ⵡⴰ ⵍⵍⴰ ⵉⵜⵎⵃⴰⵏ ⵉⵅⵓⴱⴰⵙ |

| Latin transliteration | Ha lobnan bnidax Wa lla itmḥan ixobas |

| Literal translation | Lebanon is in front of us suffering |

| English translation | I see Lebanon’s suffering |

Adaptation was used in this segment, with “Lebanon is in front of us suffering” translated as “I see Lebanon’s suffering”; “in front of us” was omitted because the meaning is understood even with omission.

Sixteenth segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵡⴰ ⵢⴰⵎⵓⵎⵅ ⵓⵔⵉ ⵜⵄⵏⵉ ⵛⴰ |

| Latin transliteration | Wa yamomex ori tεni ca |

| Literal translation | I am skinny and suffering |

| English translation | I am becoming skinnier and not feeling well |

Here, the comparative “skinnier” is more efficient in terms of accuracy than the adjective “skinny.” Furthermore, for better meaning conveyance, the use of “not well” was preferable and to the point.

Seventeenth segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵡⴰ ⵢⴷⴰ ⵍⵄⵉⵔⴰⵇ ⵣⵢⵓⵏ ⵍⴰⵜⵔⵓⵅ ⵉ ⵚⴱⵢⴰⵏ ⵍⴰⵜⵎⵜⴰⵜⵏ ⴷⵉⵖⵓⵏ |

| Latin transliteration | Wa yda lεiraq zyon latrox i sbyan latmtaten diɣon/td> |

| Literal translation | Gone Iraq is from you, I am crying for the children dying among you |

| English translation | Iraq is gone, and I am crying over the dying children |

In this segment, multiple techniques have likewise been used in order to translate the meaning. First, there is the omission of the personal pronoun “you.” Secondly, the structure is very different in the TL. Thirdly, there is also the omission of the personal pronoun in “among you.”

Eighteenth segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⵡⴰ ⵙⵔⵔⴼⴰⵜ ⵍⵎⵛⵜⵉⴱⴰⵜ ⴰⵎⵓⵜⵜⵍ ⵍⵍⴰ ⴷⵉⵙⵓⴳⵓⵔ |

| Latin transliteration | Wa serrfat lmectibat Amottel lla disogor |

| Literal translation | Do as meant to be, karma is looking |

| English translation | Follow destiny, karma is watching2 |

The most significant technique to be noted here is the use of domestication by employing the word “karma”—even if it is a term related to Buddhism, it is widely used in the West and it is more comprehensible than the SL term, “Amottel.”

Ninetieth segment

| Tifinagh transcription | ⴰⴷⵊ ⴷⴷⵄⵓⵜ ⵉ ⵔⴱⴱⵉ ⴰⵜⵜⵉⴱⴹⵓ ⵓⵔ ⵜⵜⵓⴳⵉⵔ |

| Latin transliteration | Adj ddεot i rbbi attibdo or ttogir |

| Literal translation | Let the matter to God to handle, it isn’t bigger than him |

| English translation | Leave this matter to God, it is not something he cannot handle |

Although poetry does not always comply with such rules, meaning conveyance in this last couplet requires a bit of interference with structure. The above translation might be more adequate in terms of proper language use.

Commentary on Findings

The research findings on Tamazight-English translation techniques offer profound insights into the intricate process of transferring meaning between two distinct linguistic and cultural systems. From the addition of words for clarity to the nuanced navigation of personal pronouns and the inclusion of omitted ones, translators must deftly balance linguistic fidelity with comprehensibility in the target language. Moreover, the recognition of cultural nuances and context underscores the translator’s crucial role as a cultural mediator. The tension between literal translation and conveying meaning highlights the complex decisions translators face, often requiring creative solutions to bridge linguistic gaps. Challenges abound in translating metaphors, necessitating inventive techniques to faithfully capture their essence. Modulation, transposition, and the interchangeability of active-passive voices emerge as indispensable tools for achieving linguistic harmony and cultural resonance. Additionally, the recognition of differences in collocations between Tamazight and English underscores the need for adaptation to ensure naturalness and coherence in the target language. Finally, the role of explanation emerges as pivotal in bridging profound cultural disparities, facilitating mutual understanding, and fostering cross-cultural communication. Together these findings illuminate the rich tapestry of Tamazight-English translation, reflecting the intricate interplay of language, culture, and artistry in the transmission of meaning across linguistic boundaries.

Domestication is employed more often than foreignization in Tamazight-English translation, as it helps make the text more accessible to English-speaking audiences by adapting cultural references, idioms, and metaphors into familiar terms, thereby reducing cultural distance. While foreignization is used selectively to retain certain unique Tamazight expressions and cultural nuances, domestication remains the preferred strategy, offering a smoother reading experience and resolving many of the complexities associated with translating Tamazight’s distinct linguistic features into English.

Conclusion

Tamazight remained an oral language for a long time, a fact that cost it a lot of linguistic and cultural losses while also compromising its historical heritage, transferred by oral communication from one generation to the next. Currently, scholars are making efforts to preserve and trace back what is left of this language data. This study served as an attempt to contribute to these efforts. By translating one of the cultural aspects of any culture—namely, songs—this study provides some answers to the question of how to translate from Tamazight into English while addressing some linguistic features of Tamazight. Moreover, a great deal of this culture’s history is found in its poetry. It played a prominent role in Amazigh culture, as its tribes manifested it in their daily life at work, mainly in agriculture, and it provided a significant channel for expressing their feelings, suffering, and hopes.

The oral nature of these songs made the translation difficult because of the numerous varieties of dialects of Tamazight as well as the transcription. Even within the same dialect, words may differ in terms of pronunciation and thus in their transcription. The standardized script of Tamazight, Tifinagh, is sometimes inadequate because it derives from different dialects; however, the use of the dictionary of standardized Tamazight words was of significant help in tackling this issue.

Furthermore, Islam had a considerable impact on Imazighen as they easily adopted the religion and the language of the Quran and neglected their own. Islam is not to blame, nor is Arabic. However, the Amazigh people should have preserved their language long ago so as to shield their real identity while being open to other cultures. Nevertheless, Islam has improved significant aspects of Amazigh life, especially regarding spirituality and rules of social conduct, as Imazighen show in their songs, such as the second song in this study’s analysis “Idda Zman”. Finally, this study served as an attempt to provide some insights for foreigners into our culture. At the same time, it provided proof for the translation community of how interesting and complex Tamazight translation can be.

This research on Tamazight-English translation highlighted several key techniques: careful addition and omission while balancing fidelity with comprehensibility. Creative solutions bridge gaps between literal translation and meaning conveyance. Also, flexibility in Tamazight’s sentence structure, especially in poetry, requires the maintenance of aesthetic qualities. Nonetheless, challenges with metaphors necessitate inventive techniques. Modulation, transposition, and active-passive voice interchangeability are crucial tools. Finally, adapting collocations ensures naturalness and coherence, while explanations bridge cultural disparities, fostering cross-cultural communication.

References

Binaoui, A. and M. Moubtassime. 2023. Translatability of Tamazight Songs into English (case study: famous songs by the Moroccan artist Mohamed Rouicha). Proceedings of the international conference Languages, Culture, and Media at the Crossroads. 22 and 23 December 2023. Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences Dhar El Mahraz, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University [Unpublished].

Chaker, S. 2004. Langue et littérature berbères. Paris: Clio voyages culturels.

Eco, U. 2001. Experiences in Translation. Toronto: Toronto Press Inc.

El Aissati, A. 2005. “A socio-historical perspective on the Amazigh cultural movement in North Africa.” Afrika Focus 18(1):59-72.

Fishman, J. 1990. “What is reversing language shift and how can it succeed?” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 11(1):5-36.

Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe. “Missions de l’IRCAM.” (n.d.). Retrieved October 27, 2024, from https://www.ircam.ma/fr/ircam/missions-de-ircam

Low, P. 2005. “The pentathlon approach to translating songs.” In D. L. Gorlée (ed.) Song and Significance: Virtues and Vices of Vocal Translation. Amsterdam: Rodopi: 185-212.

Munday, J. 2016. Introducing Translation Studies: Theories and Applications (4th ed.). Routledge. London.

Newmark, P. 1981. Approaches to Translation, Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Newmark, P. 1985. The translation of metaphor. In W. Paprotté and R. Dirven (eds.) The Ubiquity of Metaphor. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company: 295-326.

Palumbo, G. 2009. Key Terms in Translation Studies. Great Britain: Continuum International Publishing Group.

Shuttleworth, M. 2014. “Translation studies and metaphor studies: Possible paths of interaction between two well-established disciplines.” In Translating Figurative Language, D. R. Miller and E. Monti, eds. 53-65. Bologna: Centro di Studi Linguistico-Culturali.

University of the Witwatersrand. (n.d.). literature review and theoretical framework—WIReDSpace. https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10539/1609/02Chapter2.pdf?sequence=5/1000

Venuti, L. 1995. The Translator’s Invisibility: a History of Translation. London: Routledge.

Venuti, L. 1988. “Translation strategies.” In Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, M. Baker ed. 240-244. London: Routledge:.

Vinay, J.-P. and J. Darbelnet. 1995. Comparative stylistics of French and English: A methodology for translation, trans. J. C. Sager and M.-J. Hamel. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Yang, W. 2010. “Brief study on domestication and foreignization in translation.” Journal of Language Teaching and Research 1(1):77-80.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 3 • Issue 1 • Spring 2025

Pages 22-40

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University