A Tale of Two Cultures: Comparative study of “Iɣed n Tinnurt” from Infusen and Aschenputtel from Germany

AUTHOR: Mazigh Buzakhar

Peer Reviewed Article

A Tale of Two Cultures: Comparative study of “Iɣed n Tinnurt” from Infusen and “Aschenputtel” from Germany

Mazigh Buzakhar

Tira for Research and Studies

Abstract: This article explores the cultural significance of ancient tales, focusing on narratives from the Idraren n Infusen (Nafusa/Nefusa Mountains) in Libya and the Grimm Brothers’ collection from 19th-century Europe. The article proposes a comparative analysis of two specific tales: “Iɣed n Tinnurt” from the Amazigh town of Ifran/Yefren and “Aschenputtel” from the Grimm Brothers’ collection. Both tales feature protagonists who endure hardships and ultimately triumph, symbolizing resilience and continuity. The narratives also share common themes and symbols, such as the use of ash and silver. The article argues that these similarities reflect a shared narrative heritage across the Mediterranean between Tamazgha and Europe. The article also underscores the crucial role of women, particularly in the Amazigh culture in Idraren n Infusen, in preserving these tales. Considering the limited resources available for researching and documenting ancient Amazigh tales from Idraren n Infusen, I present this preliminary study in the hopes of inspiring further exploration in this field and contributing to the preservation of the ancient Amazigh tales from Idraren n Infusen in the face of rapid globalization. The article emphasizes the importance of recording and documenting these ancient narratives for their social and scholarly value.

Keywords: Amazigh, Idraren n Infusen, Oral Tradition, Tales, Grimm Brothers.

Introduction:

Tales and stories have long served as cultural cornerstones, capturing the essence of human experience across time and space. They are not mere entertainments but vessels of wisdom that are passed down through the ages. A rich tapestry of narratives has been produced from ancient times by unknown authors. However, if these narratives “must have an author, it would be the people” in the space spanning from the majestic Idraren n Infusen (Nafusa Mountains) in Tripolitania, Libya, to the era of Romanticism that swept across 19th-century Europe.[1] This period gifted us with the Grimm Brothers and their renowned collection of folktales, Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales).

These ancient tales and stories have been preserved through oral tradition over the ages, but beyond this form of transmission, collecting and preserving ancient tales and stories are crucial activities that will help maintain cultural memories and strengthen identity. These narratives, deeply intertwined with their socio-cultural context, serve as a rich source of historical knowledge, offering insights into the lives, beliefs, and values of our ancestors passed from one generation to another (طالة 2020, 175). Stories form the backbone of any nation’s cultural heritage, fostering a sense of identity and continuity. All societies understand that preserving their stories ensures that their future generations will learn from their past, understand their cultural roots, and develop a sense of identity and belonging in their community. In the Amazigh context, it is certainly important to document and preserve ancient tales in order to advance research in linguistics and oral tradition studies but also in order to deepen the Amazigh identity in the younger generations of Imazighen. These stories have the potential to enhance scholarly understanding of textual transmission, Imazighen’s historical context, and societal dynamics. The act of preserving them transcends mere historical conservation; it also shapes the trajectory of Imazighen’s collective future.

In this article, I will utilize a basic comparative analysis to identify similarities and common patterns between a tale from Idraren n Infusen and another from Germany.[2] My analysis focuses on the content of these narratives and the nature of the regions from which they originate. This method will allow me to draw parallels, identify contrasts, and ultimately gain a more profound understanding of the intricate relationship between the regions of the southern and northern Mediterranean, their literature, and the cultural nuances they share and that their stories encapsulate. This analysis examines characters and pivotal events within both tales, aiming to comprehend the roles of protagonists, antagonists, and other significant figures in the stories. The article widens its scope by exploring the meaning of the symbolism of elements such as silver, ashes, and birds. These symbols play a crucial role in shaping the narratives and are deeply rooted in their cultural context.

Ancient Amazigh Tales (Infusen Mountains Region)

In order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the Amazigh language and culture, it is essential to delve into the literature that has been orally preserved for centuries by the elder women, or Tiwessarin, in Idraren n Infusen.[3] During periods of instability and limited record-keeping, it was Amazigh women who performed the crucial task of preserving these Tinfas (tales) from oblivion.[4]

Beyond the context of instability and warfare, Amazigh women shielded Imazighen’s ancient narratives from loss, preserving it for the subsequent generations, who regrettably lacked the foresight to protect these tales from the impact of modernity and its external cultural influences. Whether it was language or religious aspects like Arabization, these influences had a significant impact (Sahli 1959) on oral culture, leading to the loss and disappearance of most of Imazighen’s ancient tales in Idraren n Infusen. [5] As a result of this historical process, only a few have been recorded and documented.[6] It is worth noting, however, that Amazigh poetry and proverbs once constituted a rich literature written by authors from the Infusen region during different dynasties, such as the Rustamid Dynasty (Kaak 1955).[7] In general, traditional Amazigh literature was acknowledged by Ibn Khaldun in his important book Kitāb al-ʿIbar (Akbouch 2020:104).

These tales had social and cultural value for Imazighen. Ancient tales served as vessels for ancestral wisdom, captivating the minds of young listeners. Tawessart, elderly women in the Tamazight variant of Tanfusit/Tayefrnit, would weave narratives like tale of “Jriba” or “Tafunast n Igujilen”[8] or the tale of “Lullja;” they would start an introduction in gentle voices to create the atmosphere, transporting the children into realms of fantasy, imagination, and heroism.[9] The enduring importance of these ancient tales resides in their diverse expressions, which act as a ceaseless source of symbols, motifs, and mythemes (Zahir 2022). These oral traditions mirrored the cultural heritage, values, and experiences of the Imazighen, echoing throughout Idraren n Infusen mountains.

Traditionally, the ancient Amazigh tales of Idraren n Infusen had a unique structure and form, encompassing tales of character metamorphoses, as in the tale of “Tanεuct” or “Tamedrart,” for example.[10] Both the tales of “Tanεuct” and “Tamedrart” explore the theme of human transformation caused by intense emotions. In “Tanεuct,” sorrow and rage transform a human into an owl, while in “Tamedrart,” similar feelings lead to a transformation into a caper plant.[11] For example, the tale of “Tanεuct” describes:

A woman went to a wedding and took her little son with her. Her little son played and was naughty like all children. One of the women present at the wedding said to his mother, “You must stop your son from what he is doing. He has been naughty ever since he arrived.” So, his mother went and scolded him and disciplined him and asked him to stay calm. That little boy did not listen to what his mother said to him. So, she went to him again and grabbed him and started beating him and beating and beating him. The women present did not intervene, and the child was crying, and the women were laughing at his mother for beating her son. The mother became very angry and beat her son even more out of anger until the boy died in her arms. The women were still laughing and gloating over her. The child’s mother cried and took out her Tamelfa (black veil) and covered herself with it and turned into a black bird (Owl) called Tanεuct. Before flying in the sky, she told the women present that she would kill their children and make them cry and laugh as they laughed then. She went up and flew in the sky. From that day forward, it is said that if a baby is left unattended at night exposed, the black owl will swoop down, flapping its wings over the infant's head, bringing sickness and death.

Additionally, there are tales of female saints such as “Tanfust Nanna Zuraɣ” or “Tanfust nanna tala” (Buselli 1924). Historically, these wise women once resided in Idraren n Infusen, were renowned for their wisdom, and were considered oracles of the mountains. Moreover, there are tales from the animal kingdom like the tale of “Uccen d Tili” (Wolf and the sheep) or “Insi d Uccen” (Hedgehog and the Wolf). These narratives provided a window into the Imazighen worldview through the voices of Amazigh women, illustrating their interactions with and interpretations of life, death, continuity, and existence.

The Grimm Brothers’ contribution to the preservation of German traditional tales is of monumental significance. The work was not merely a collection of stories, but a meticulous preservation of Germany’s rich oral folklore tradition. The brothers ingeniously wove elements of Romanticism into these tales, thereby evoking a sense of wonder and enchantment (Abdulhadi 2023:5). This infusion of Romantic elements transformed the tales into fantastical narratives, rich in imagination and steeped in cultural significance. Their work stands as a testament to the power of storytelling and its ability to capture and convey the essence of a culture’s history, values, and beliefs (Joosen and Kümmerling-Meibauer 2021). Many ancient Amazigh tales from Idraren n Infusen, remaining solely oral, lacked the opportunity to be developed and transformed into fantastical narratives; unlike the German tales shaped by the Grimm Brothers, these tales haven't had the opportunity to evolve and be reimagined through a written form.

In the early 1800s Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, known today as the Grimm Brothers, began collecting German folklore. Their first edition of the collection, titled Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales), was published in two volumes in 1812 and 1815. This seminal work is a compilation of over 200 traditional folk tales, painstakingly collected and transcribed to preserve Germany’s oral storytelling tradition. The tales range from the familiar, like “Aschenputtel” (Cinderella), “Rotkäppchen” (Little Red Riding Hood), “Hänsel und Grethel” (Hansel and Gretel), and “Rapunzel” (Rapunzel), to lesser known yet equally enchanting stories. The Grimms’ versions often have darker, more complex themes than their later adaptations, reflecting the harsh realities of life in the 19th century (German Culture 2024).

Beyond the Hearth: “Aschenputtel” and Iɣed n Tinnurt's Journeys

Before delving into the comparative analysis of these tales, let us first familiarize ourselves with “Iɣed n Tinnurt” and “Aschenputtel.” The ancient Amazigh tale of “Tanfust Iɣed n Tinnurt” originates from the mountainous region of Infusen. Although there is a singular rendition of this ancient story from the town of Ifran/Yefren, it was Mr. Said Shnaib who first introduced it in the 2000s. His presentation was part of a broader anthology of venerable Amazigh tales that he shared on the Tawalt website.[12] These tales, known as Tinfas, were published in Tamazight, specifically the Tayefrnit variant, accompanied by Arabic translations.[13] Notably, the Arabic versions were not direct translations but rather interpretative renditions. Regrettably, details regarding the origins of these Tinfas—the specific villages in Ifran from which they were collected and the identities of the storytellers—remain unknown.[14] Understanding the provenance of these ancient Amazigh tales is crucial, as it could illuminate the diverse oral traditions of Ifran and the broader region of Idraren n Infusen.

Nonetheless, Mr. Shnaib’s collection of ancient tales, showcased on the Tawalt website, is encapsulated in the “Tinfas n Nanna” series, which features 14 ancient tales. The specific stories explored in this study are not only fascinating in their own right but also resonate with the rich tapestry of cultural folk tales. The analysis I provide here seeks to illuminate the parallels between these tales and their counterparts across the Mediterranean, revealing a shared narrative heritage. Notably, celebrated tales such as “Tanfust n Lulja” (Tale of Lulja), “Tanfust n insi d uccen” (Tale of Hedgehog & the Wolf), “Tanfust n azgen bucil, bu-nfiṣ” (Tale of Half-Human), and “Tanfust n Tɣaṭ d Iɣayden-nnes” (Tale of Goat and Her Kids), among others are prevalent across the towns of Idraren n Infusen from Ifran, Jadu, Fersetta, Kabaw and Lallut (Nalut), further enriching our understanding of the region’s preserved past.[15]

The tale of “Iɣed n Tinnurt” is noteworthy in this study due to its unique narrative structure and intriguing parallels with the story of “Aschenputtel.” It narrates the life of a man and his three daughters, who are left motherless by the untimely demise of his wife. The subsequent marriage of their father to another woman introduces a cruel stepmother into their lives, who mistreats the daughters. Notably, among the siblings, the two other daughters are described as heavy eaters, while the youngest stands out as the petite and youthful one.[16] The three sisters embark on disparate paths of rejection, which I would describe as their father’s attempt to abandon them, succumbing to the persistent entreaties of his wife. He seeks various ways to leave his daughters in the wilderness while returning to his cruel wife (the stepmother)—whether to fend for themselves in the solitude of the forest or find themselves into the forsaken water well in search of their father’s lkembus.[17]

In terms of its broader significance, the tale represents the battle of wills as the innocent youngest daughter Iɣed n Tinnurt endeavors to sway her father’s heart, urging him to turn a deaf ear to the harsh whispers of her cruel stepmother.[18]

The Grimm Brothers’ anthology of fairy tales is an essential gateway to the rich tapestry of German folk narratives. Among these, the tale of “Aschenputtel,”[19] or “Cinderella” as it is widely known in English literature, is a well-known story. This narrative, weaving themes of inherent goodness triumphing over malice, has etched itself into the bedrock of Western children’s storytelling. The story unfolds with “Aschenputtel,” a young woman beset by the loss of her mother and the cruelty of her stepfamily. Yet, she remains the epitome of compassion and diligence. She finds her sole comfort in the hazel tree rooted atop her mother’s resting place, where she seeks refuge in prayer (McLoone 2015). This tree burgeons into a beacon of her mother’s unwavering affection and guardianship, bestowing upon her splendid gowns for the royal gala.

In the Grimm Brothers’ rendition of Cinderella, the narrative takes on a more gloomy and intricate tone compared to its subsequent retellings. The tale eschews the traditional fairy godmother archetype; rather, it is the ethereal presence of Aschenputtel’s deceased mother that provides her with assistance (Tearle 2015). This poignant detail weaves a profound subtext into the fabric of the story, casting a spotlight on the enduring strength of maternal affection—a force that not even the finality of death can diminish. The tale also explores the theme of justice. The stepmother and stepsisters, who mistreat Aschenputtel, face a grim punishment, unlike in other versions where they are forgiven (Tearle 2015).[20] This harsh retribution underscores the moral that cruelty and deceit are ultimately self-destructive. We will examine the tale in greater detail as we apply basic comparative analysis to explore a similar story in Tamazight from Ifran/Yefren called “Iɣed n Tinnurt” and understand the similarities between the two tales.

Analyzing the Two Ancient Tales: Characters and Events

In this section, I will probe the structure and dissect the parallels between the narratives of these two tales. It is important to acknowledge that this examination of the two stories cannot be exhaustive and, instead, aims to spur extensive research in the future.

In this examination, I have used the English version of the Grimm Brothers’ “Aschenputtel” from the version entitled Household stories from the collection of the Bros. Grimm, translated by Lucy Crane. As I previously mentioned, I will examine the ancient tale of “Iɣed n Tinnurt,” presented by Mr. Shnaib and shared on Tawalt.com (the tale was revised and edited to align with the Tamazight Latin orthography for this study, along with the English translation).

In this section, I will examine and accentuate the salient features to be found within the narratives “Iɣed n Tinnurt” and “Aschenputtel.” This examination will encompass a discussion of the dramatis personae, an etymological exploration of the protagonist’s nomenclature, and an evaluation of the main events in terms of their features. Furthermore, this section will identify and compare the overlaps in events for the tales.

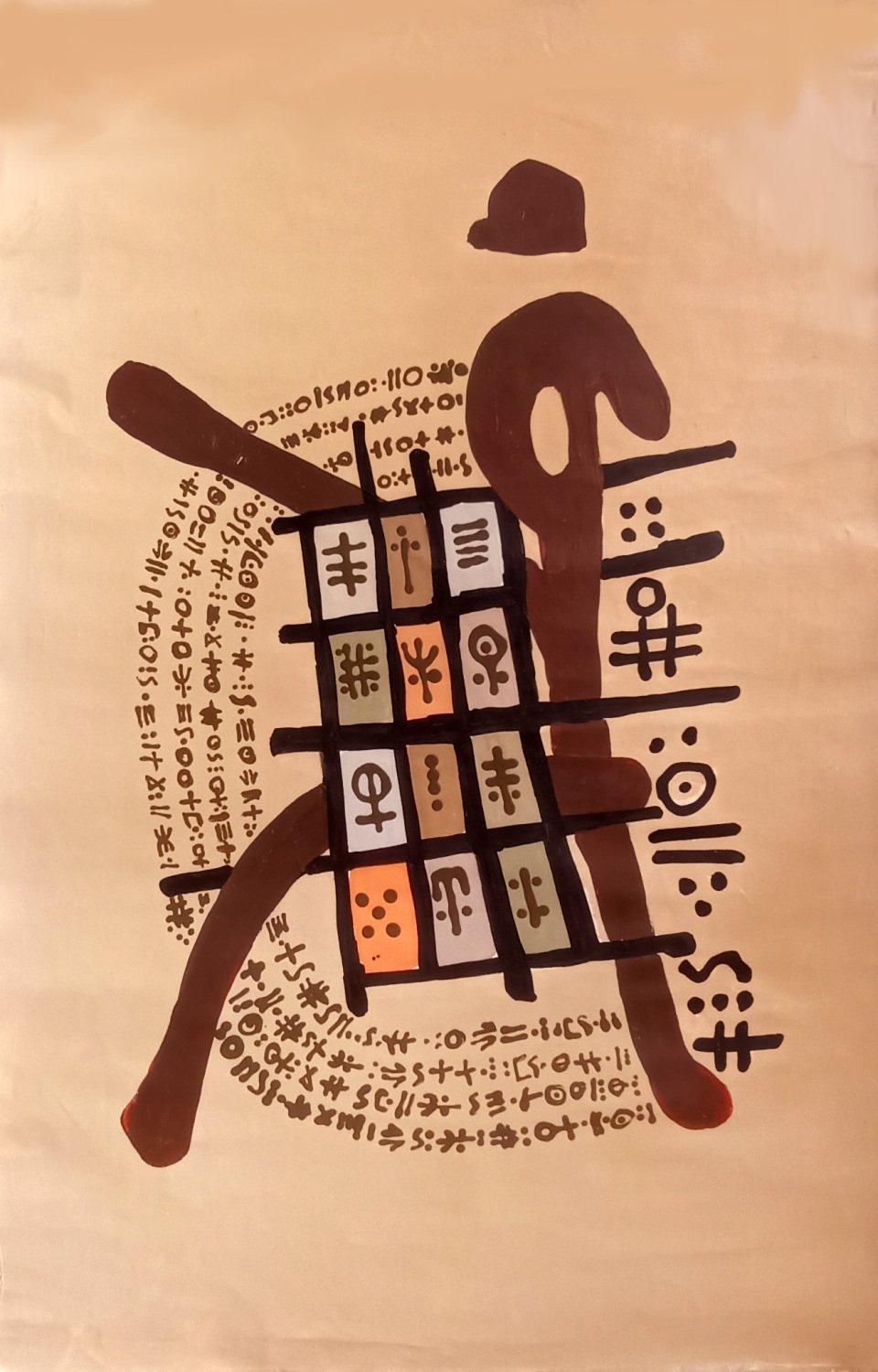

To facilitate this comparative study, the following tables were created to delineate the constituent elements that shape the structure of these narratives.

Table-1 Tale of “Aschenputtel”:

| Character | Role in the Story | Key Events |

|---|---|---|

| Aschenputtel | Protagonist; the youngest sibling | - Endures the death of her mother

- Suffers mistreatment at the hands of her stepmother and stepsisters - Performs arduous tasks as a maid - Receives magical assistance from avian friends - Obtains elegant attire and slippers from a bird perched upon a hazel bush - Attends the royal festival, captivating the prince with her grace - Ultimately identified by the prince through the golden shoe, confirming her as his true bride |

| Rich Man | Aschenputtel’s Father | - Remains passive during the mistreatment of his daughter |

| Sick Wife | Aschenputtel’s Mother | - Her demise sets the narrative into motion |

| Stepmother | Antagonist | - Inflicts hardship upon Aschenputtel, relegating her to servitude |

| Stepsisters | Secondary Antagonists | - Partake in the ill-treatment of Aschenputtel |

| Pigeons | Symbolic Helpers | - Provide Aschenputtel with moral and material support |

| Prince | Love Interest | - Seeks to find the mysterious maiden who enchanted him at the festival |

Table-2 Tale of “Iɣed n Tinnurt”:

| Character | Role in the Story | Key Events |

|---|---|---|

| Iɣed n Tinnurt | Protagonist; the youngest sibling | - Similar to Aschenputtel

- Endures the death of her mother stepsisters - Suffers mistreatment at the hands of her stepmother and her two elder sisters - Performs arduous tasks as a maid to her two elder sisters - Receives her name from her elder sister |

| Deceased Wife | Iɣed n Tinnurt’s Mother | The narrative begins with the mother’s demise, setting the stage for subsequent familial conflicts |

| Husband | Iɣed n Tinnurt’s Father | The protagonist endures repeated attempts by her father to abandon them and suffers continuous mistreatment at the hands of her stepmother and elder sisters |

| Iɣed n Tinnurt’s Siblings | Protagonist + Antagonist | The protagonist endures repeated attempts by her father to abandon them and suffers continuous mistreatment at the hands of her stepmother and elder sisters |

| Stepmother | Antagonists | The protagonist endures repeated attempts by her father to abandon them and suffers continuous mistreatment at the hands of her stepmother and elder sisters |

| Tergu | The discovery of Tergu’s dwelling marks a turning point, leading to a series of transformative events for the protagonist | |

| Sultan’s Son21 | Emerge as pivotal figures | -The protagonist’s wedding and the subsequent envy of her sisters catalyze further developments

- The loss and retrieval of the protagonist’s Terlik22 in a water well culminates in the quest of the sultan’s son to find the true bride |

This detailed information demonstrates that “Aschenputtel” and “Iɣed n Tinnurt” offer rich narratives for comparative analysis. These narratives share cultural similarities, resonating particularly well within the Mediterranean context since they echo elements found in the tales of the Jewish-Moroccan Cinderella story “Smeda Rmeda,”[23] the Greek “Stachtopouta,”[24] and the Italian fairytale “Cenerentola.”[25] As Chadili eloquently argues, the shared history of the Mediterranean peoples—shaped by wars, migrations, and trade—has profoundly influenced their collective imagination. This shared cultural heritage, spanning across the entire region, is evident in the common themes and motifs found in myths, tales, epics, and fables (الشاذلي الداهي 2009).

Both stories feature protagonists—Aschenputtel and Iɣed n Tinnurt—whose lives are marred by the death of their mothers and subsequent mistreatment by their stepmothers. The etymology of “Aschenputtel” combines German words for “ash” and “untidy girl,” reflecting her sooty existence. “Iɣed n Tinnurt,”[26] meaning “Ash of Hearth” in Tamazight, referring to the ash was used by Iɣed n Tinnurt to mark the route back home when she and her sisters were left alone in the forest by their father, similarly uses ash as a metaphor for resilience and rebirth.[27]

In both tales, we can observe how ash plays a pivotal role, symbolizing not only the protagonists’ lowly status but also their potential for transformation and protection. This resonates with the Roman mythology of the Vesta[28] goddess of the hearth and home, symbolized by the hearth itself, the source of ash.[29] Marriage serves as a key turning point in both tales, marking the protagonists’ societal ascent and personal triumph over adversity or possibly a continuity.[30] The essential similarities between the two tales from the tables—maternal death, servitude, magical assistance, loss of footwear (slipper or Terlik), and eventual marriage to a powerful figure (prince or sultan’s son) —highlight the shared thematic core of these tales.

Analyzing the Two Tales: Prince Versus the Sultan’s Son

If we examine the Grimm Brothers' “Aschenputtel,” we can see that the prince's search for his true love is aided by two white pigeons, which could symbolize purity and truth. After the festival, the prince is left with only a golden slipper to find the mysterious maiden who stole his heart. He travels across the land, decreeing that the woman whose foot fits the slipper shall be his bride.

At Aschenputtel's home, her stepsisters, driven by greed and deceit, mutilate their feet to fit the slipper. However, as each sister presents herself to the prince, the white pigeons perched on the hazel tree cry out:

There they go, there they go!

There is blood on her shoe;

The shoe is too small,

Not the right bride at all![31]

When it is Aschenputtel’s turn to try on the slipper, the prince, finding it to be a perfect fit, sweeps her onto his horse as his bride. Together, they ride past the grave where two pigeons are perched upon the hazel bush, their cries echoing:

There they go, there they go!

No blood on her shoe;

The shoe's not too small,

The right bride is she after all.[32]

The pigeons’ divine song reveals the truth, which comes from the voice of Aschenputtel mother’s soul, sparing the prince from a false match. When Aschenputtel tries the slipper, it fits perfectly, and the pigeons sing in joyous confirmation. The prince recognizes the truth of Aschenputtel's claim thanks to the slipper. We can learn from the tale that with the pigeons' guidance, the prince finds his true bride, and Aschenputtel's goodness is rewarded, showcasing the triumph of truth and virtue over deception.

The sultan’s son in “Iɣed n Tinnurt” parallels the prince in “Aschenputtel”. Let us now explore how the sultan’s[33] son came to find the owner of the Terlik—a traditional, ornate slipper.[34] The story reveals a twist of fate: the sultan’s son did not encounter Iɣed n Tinnurt at the wedding festival. Instead, it was while watering his horse that he stumbled upon the Terlik inside a pool next to the water well.[35] He took the Terlik and said, “I shall marry the owner of this slipper.”[36]

This cherished item had slipped from Iɣed n Tinnurt’s possession as she hastened home from the wedding festival. Overwhelmed by the dread of her elder sisters discovering her absence—they who had denied her company to the wedding—she flees, leaving behind the Terlik as the sole trace of her fleeting presence. The sultan’s son dispatches Aberraḥ,[37] a servant known for his ability to call on and locate people, on a mission to find the girl who owns the silver-decorated slipper. Instructed to visit every house in the country[38] and have every girl try it on to find its owner, the servant sets out on his mission to find Iɣed n Tinnurt.[39] However, there’s a significant turn in the tale when the servant learns about girls residing in a Tergu’s dwelling from an informant he meets en route to the castle. This information leads him to the owner of the slipper. Upon visiting Tergu’s dwelling, the servant hears a noise inside after the elder sisters try on the slipper, which didn’t fit either of them. Intrigued by the noise, the servant calls for the persons to reveal themselves. It is then that Iɣed n Tinnurt emerges. The servant asks her to try on the slipper, and to his delight, it fits her feet perfectly.

The Power of Symbols: Ash, Silver, Birds, and Tergu

Focusing specifically on the four symbols of ash, silver, birds, and Tergu, this section will examine the importance of these symbols in both tales. Two of these symbols, ash and silver, are prevalent in both stories. Intriguingly, the protagonists of both tales bear the symbol of ash in their names: “Aschenputtel,” the Ash-Girl, and “Iɣed n Tinnurt,” the Ash of Hearth.

A notable distinction between the tales lies in the origin of Iɣed n Tinnurt’s name. Her elder sisters bestowed this name upon her while they were trapped inside an ogress’s house beneath a water well.[40] In the narrative, Iɣed n Tinnurt rescues her elder sisters and guides them home using ash as a trail marker. This was after their father had abandoned them in the forest, intending to get rid of them. In this context, the ash in “Iɣed n Tinnurt” tale symbolizes resilience and continuity. In contrast, the ash in Aschenputtel’s story represents struggle, as seen through the hardships faced by the maiden at the hands of her cruel stepmother and stepsisters. Despite the different interpretations, Ash remains a defining symbol in both tales, shaping the narrative and the characters’ identities.

In both tales, however, the symbol of silver plays a significant role. In Aschenputtel, what she desires is silver, along with beautiful clothing. This wish arises when she decides to attend the feast despite her stepmother’s initial refusal. She expresses her wish at her mother’s grave, under the hazel tree, saying:

Little tree, little tree, shake over me,

That silver and gold may come down and cover me.

Subsequently, a bird drops a dress of gold and silver, along with a pair of slippers embroidered with silk and silver. The silver in the tale symbolizes beauty, as embodied in the dress and slippers.[41]

Similarly, in the tale of “Iɣed n Tinnurt,” silver symbolizes the jewelry found in the locked chambers that Tergu, the ogress, had forbidden Iɣed n Tinnurt from entering. These locked chambers in the ogress’s house were filled with silver jewelry, referred to as Lfujret in Tamazight, along with beautiful dresses and food.[42] It was only when Iɣed n Tinnurt managed to push the ogress into a large clay oven, known as a ‘Firnu’ in Tayefrnit, that she was able to enter these forbidden chambers. As a reward, she received silver jewelry and a beautiful dress, and was given the opportunity to attend a wedding, which her elder sisters had refused to let her join.

Another aspect that I find fascinating to compare and highlight is the symbolism of birds in the tale of “Aschenputtel,” and the ogress Tergu in “Iɣed n Tinnurt.” I have noticed that both symbols exhibit several similarities in their roles and presence within the stories. In Aschenputtel, birds are depicted as helpers and protectors of the protagonist, Aschenputtel. They provide the necessary assistance when Aschenputtel’s stepmother tasks her with sorting lentils in an effort to prevent her from attending the royal festival. It is at this point that Aschenputtel calls upon the birds for help, saying:

O gentle doves, O turtle-doves.

And all the birds that be,

The lentils that in ashes lie

Come and pick up for me!

The good must be put in the dish,

The bad you may eat if you wish.[43]

In addition to assisting with the sorting of lentils, the birds also play a significant role in fulfilling Aschenputtel’s wishes. Whenever Aschenputtel desires something, she visits the hazel tree on her mother’s grave and expresses her wishes. In response, the bird grants her wish by dropping down what she has asked for. For instance, when her stepmother and stepsisters go to the festival, leaving her alone at home, Aschenputtel seizes the opportunity to visit her mother’s grave. She expresses her wish with tears, and the bird responds by dropping down a dress made of gold and silver, along with a pair of slippers. In numerous cultures, particularly those of the Mediterranean and Northern Europe, birds are perceived as divine messengers.[44]

Let’s delve into the symbol of the Tergu, or ‘ogress,’ used in the tale. In other towns in the region of Idraren n Infusen, different terms are employed in the tales. These terms, such as the word Tamẓa, symbolize characters similar to beasts or ogresses.[45] This symbol carries significant meaning and is closely associated with the tale of “Iɣed n Tinnurt”. In the previous discussions, I explored how Iɣed n Tinnurt discovered an entrance while she was digging with her hands inside a water well.[46] This discovery within the Tergu’s dwelling marked a pivotal moment in her journey, leading her to unlock the chambers, and initiating a series of transformative events.

The Tergu’s role in the tale is somewhat limited, confined to a few key events. The first of these is when Tergu discovers Iɣed n Tinnurt. This occurs when Iɣed n Tinnurt burns her hands from a hot sickle made by Tergu, as she attempts to gather or steal some flour.[47] Marking the beginning of their intertwined destinies.[48] The second event involves Tergu adopting to Iɣed n Tinnurt when she realizes that Iɣed n Tinnurt is a human, not a Jinn. This realization comes about through a conversation in which Tergu asks, “Jens ɣen Wens,”[49] and Iɣed n Tinnurt responds, “Wens xer n Bab-nnem d Yaǧ-nnem.”[50] This exchange between the ogress and the human is intended to clarify the nature of their existence. The term ‘Jens,’ as used in the tale, refers to a jinn, an invisible being found in many pre-Islamic Arabian mythologies (Britannica 2024). This highlights the cultural and historical context of the narrative. In North African, Persian, and Turkish folklore, jinn are depicted as beings of smokeless flame, capable of assuming human or animal forms. In contrast, humans are considered to be made of earth (Britannica 2024). This concept of spirits with dual natures is echoed in other Mediterranean mythologies, such as the Roman belief in genii, or guardian spirits assigned to individuals from birth (Britannica 2024). Much like the jinn, these could be either benevolent or malevolent. This distinction is highlighted in the tale when Tergu asks, ‘Jens ɣen Wens’ in an effort to confirm the nature of the creature she’s interacting with and whether it can be trusted. The tale also reveals that the ogress shares a fear of the jinn with humans, suggesting a shared apprehension of invisible creatures. Such dialogues between Tergu and humans are common elements found in several ancient Amazigh tales from Idraren n Infusen. These interactions provide valuable insights into the cultural and mythical contexts of these narratives.

In the third event, Iɣed n Tinnurt attempts to eliminate Tergu by pushing her into an oven clay while baking bread. This is done with the intention of gaining access to the forbidden chambers, despite Tergu's warnings. Inside this locked chambers, Iɣed n Tinnurt discovers an array of ‘Lfujret' silver jewelry, exquisite dresses, and food. The only hope for Iɣed n Tinnurt to aid her elder sisters and liberate herself from Tergu is to kill Tergu. Interestingly, in the tale, when Tergu discovers that Iɣed n Tinnurt is human, she adopts her and refers to her as a daughter.[51]

I would also like to mention here a fascinating aspect of Mediterranean culture which is the naming of newborns. There is a practice found in many parts of Greece that gives unbaptized children names like Drakos (ogre) for boys and Drakou (ogress) for girls, aiming to provide magical protection (Kaplanoglou, 2016, P13). The name Tergu in the story of Iɣed n Tinnurt might hold a similar significance. Could Tergu the ogress be embodying this protective role, offering a safe haven by adopting the protagonist? In contrast, the ogress can be characterized as an antisocial (living alone in the wild) and often foolish being.[52] Thus, this discussion of the symbolism of Ash, Silver, Birds, and Tergu in the two tales reveals that Ash serves as a symbol of resilience, protection, and struggle in both stories. Silver, on the other hand, represents beauty and desire, often manifested in the form of dresses and jewelry. In the tale of “Aschenputtel”, birds play the role of helpers and wish fulfillers. Tergu, the ogress in the tale of “Iɣed n Tinnurt”, stands as a symbol of transformation (even protection).

Within the Mediterranean context, symbols like silver hold profound cultural significance. The metal's lunar associations are evident in the figure of Artemis, the Greek goddess of chastity and fertility, often depicted with a silver bow. As a protector of young women, particularly those on the verge of marriage, the dedication of childhood toys to Artemis symbolized their transition to adulthood and marital responsibilities (Cartwright 2019). Meanwhile, in Greek folk culture, ash has a polyvalent significance, embodying both cleansing and rejuvenating properties. This is reflected in the tale of “Stachtopouta,” the Greek Cinderella (Kaplanoglou 2016:2).

When we say, “A little bird told me,” we are talking legend, folklore, and superstition all at once (Ingersoll 1923:3). That’s why birds have a significant role in Mediterranean culture, representing guidance and omens. In ancient Greece, birds were frequently used to predict the outcome of future events (Goldhahn 2019), while in Roman times, omens were mainly caused by birds (Roque 2009). Meanwhile, in the Italian “Cenerentola” tale, Zezolla finds guidance in the Dove of the Fairies from Sardinia. This magical dove acts as her benefactor, granting her wishes whenever she desires. It serves as a symbol of hope and also as a messenger, guiding Zezolla towards her destiny (Basile 1850:64-65).

The interactions of the protagonists with these symbols shape their narratives, underscoring their resilience, desires, and transformations. In this paper, I have delved into the cultural and historical contexts of these symbols, which have enriched our understanding of the tales.

Conclusion

Tales serve as enduring relics of our ancestors' memories, and their preservation, documentation, and safeguarding from oral oblivion are of paramount importance. This article has focused on ancient tale from Idraren n Infusen, known as Iɣed n Tinnurt, to mark the inception of more comprehensive future research. Some of these ancient tales exist today only as audio recordings, underscoring the urgent need for their transcription and subsequent presentation for linguistic and literary research.

My study of “Iɣed n Tinnurt” and “Aschenputtel” has revealed more than just similarities and common patterns. It has shed light on the shared cultural aspects among different Mediterranean countries. Notably, we have gleaned insights into the faith journeys of both protagonists, which culminated in marriage. Both protagonists were subject to cruelty from their stepmothers and sisters (Iɣed n Tinnurt’s siblings and Aschenputtel’s stepsisters).

Through the examination of the symbols that imbue both tales with elements of fantasy and mythology, such as ash, silver, and birds, this article has shown that these symbols, when employed in tales, forge a connection to the tale's cultural roots and rituals. The article has demonstrated that silver holds a unique position in Amazigh culture in the region of Idraren n Infusen, paralleling the significance of jewelry in European culture. Silver has dominated Amazigh jewelry for a long time, reflecting both aesthetic preferences and rural traditions across Tamazgha, while gold was recently introduced in the jewelry design (Camps-Fabrer 1991). That’s why Imuhagh/Tuareg avoid gold for superstitious reasons, believing it carries a curse, as depicted in Al-Konie’s novel Gold Dust (شريّط 2024:15).[53]

Although this comparative study raises more questions than answers, I hope that it paves the way for further research. How did these tales with similar protagonists traverse the Mediterranean? Was “Aschenputtel” the original tale that later spread to Tamazgha, or was it the other way around? Why do both tales use ash to both describe and name the protagonist? Why was silver used as a symbol in both tales, and does it have any connection to rituals or deities? How old are these tales? These questions open the door for more extensive research, potentially exploring other tales from Tamazgha that bear similarities to “Iɣed n Tinnurt” and delving deeper into the ancient oral traditions on both shores of the Mediterranean.

Reference

Abdulhadi, O. Mohammad Althobaiti. 2023. “The Evolution of European Fairy Tales: A Comparative Analysis of the Grimm Brothers and Hans Christian Andersen.” European Scientific Journal 19(23):43-52.

Alberini, Elena Schenone. 1999. Libyan Jewellery: A Journey Through Symbols. Italy: Araldo de Luca Editore.

Bar-Itzhak, Haya and Aliza Shenhar. 1993. Jewish Moroccan Folk Narratives from Israel. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Basile, Giambattista. 1850. The Pentamerone, or The Story of Stories. Translated by John Edward Taylor. Second Edition. London: David Bogue.

Berger, Philippe. 1877. Tanit Penē-Baal. Paris: Impr. Nationale.

Britannica, Editors. 2024. “Grimm’s Fairy Tales.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed May 20. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Grimms-Fairy-Tales

Britannica, Editors. 2024. “Jinni.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed May 27. https://www.britannica.com/topic/jinni.

Britannica, Editors. 2012. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “genius.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed January 16. https://www.britannica.com/topic/genius-Roman-religion.

Buselli, Gennaro. 1924. “Berber Texts from Jebel Nefûsi (Žemmâri Dialect).” Journal of the Royal African Society 23(92):285-293.

Camps-Fabrer, H. 1991. “Bijoux.” Encyclopédie berbère 10:1496-1516.

Cartwright, Mark. 2019. “Artemis.” World History Encyclopedia. Accessed November 01, 2024. https://www.worldhistory.org/artemis/.

Dallet, J.-M. 1972. Dictionnaire Kabyle-Français: Parler des Ait Mangellat, Algérie. Paris: Société d’études linguistiques et anthropologiques de France.

Luu, Chi. 2018. “The Fairytale Language of the Brothers Grimm.” JSTOR Daily. Accessed June 3, 2024. https://daily.jstor.org/the-fairytale-language-of-the-brothers-grimm/

German Culture. “Grimm’s Brothers Fairy Tales.” Accessed June 4, 2024: https://germanculture.com.ua/famous-germans/grimms-brothers-fairy-tales/

Goldhahn, Joakim. 2019. Birds in the Bronze Age: A North European Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Grimm, Brother. 1922. Household Stories from the Collection of the Bros. Grimm. Translated by Lucy Crane. London: Macmillan & Co.

Ibn Khaldoun. 1856. Histoire des berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique septentrionale. trans. M. Le Baron De Slane. vols. 3. Alger: Imprimerie du gouvernement.

Ingersoll, Ernest. 1923. Birds in Legend, Fable, and Folklore. New York: Longmans, Green and Co.

Hagan, Helene E., and Lucile C. Myers. 2006. Tuareg Jewelry: Traditional Patterns and Symbols. Bloomington, IN: Xlibris Corporation.

Joosen, Vanessa, and Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer. 2021. “Introduction: The Legacy of the Grimms’ Tales in Picturebook Versions of the Twenty-First Century.” Strenæ 18. Accessed May 25, 2024. https://doi.org/10.4000/strenae.6515

Kaak, Othman. 1955. “Al Barbar.” n.p.: n.p. Archive. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://archive.org/details/1955_20211129/page/44/mode/2up

Kabir, Syed Rafid. 2022. “Vesta: The Roman Goddess of the Home and the Hearth.” History Cooperative, November 23. https://historycooperative.org/vesta-goddess/. Accessed November 2, 2024.

Kaplanoglou, Marianthi. 2016. “Spinning and Cannibalism in the Greek ‘Cinderella’: Symbolic Analogies in Folktale and Myth.” Folklore 127(1):1-25.

Lacoste-Dujardin, Camille. 2013. “Ogre et ogresse (Kabylie).” Encyclopédie berbère 35:5720-5721.

Lanfry, Jacques. 2011. Dictionnaire de berbère libyen (Ghadamès). Tizi-Ouzou: Editions Achab.

McLoone, Juli. 2015. “Fairy Tale Fridays: Aschenputtel.” Beyond the Reading Room, University of Michigan Library. Accessed May 25, 2024. https://blogs.lib.umich.edu/beyond-reading-room/fairy-tale-fridays-Aschenputtel/

Calassanti-Motylinski, Adolphe de. 1898. Le Djebel Nefousa: Transcription, Traduction Française et Notes avec une Étude Grammaticale. Paris: Leroux.

Roque, Maria-Àngels. 2009. “Birds: Metaphor of the Soul.” European Institute of the Mediterranean. Accessed May 21, 2024. https://www.iemed.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/Birds.pdf

Sahli, O. 1959. Nafousa. Berber Community in Western Libya. B.A. Thesis. University of Libya.

Streich, Mike. 2017. “Women in the Ancient Mediterranean World,” Short History, 2017

Tearle, Oliver, Dr. 2015. “A Summary and Analysis of the Cinderella Fairy Tale.” Interesting Literature. Accessed May 14, 2024. https://interestingliterature.com/2015/04/a-summary-and-analysis-of-the-cinderella-fairy-tale/

Wang, Xiulu and Chuanji Hu. 2021. “Similar archetypes and different narratives: a comparative study of Chinese ‘Yeh Hsien’ and European Cinderella stories.” Neohelicon 48:245–255.

Zahir, Mohamed. 2022. “The Amazigh Novel, Mythology of Origins, and Return of the Repressed: A Titrological Approach.” Translated by Tegan Raleigh. Review of Middle East Studies 56(2):313–29.

Zipes, Jack. 2024. “How the Grimm Brothers Saved the Fairy Tale.” Humanities: the Magazine of the National Endownment for the Humanities. Accessed on May 20, 2024. https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2015/marchapril/feature/how-the-grimm-brothers-saved-the-fairy-tale

طالة، لامية. 2020. ”الحكاية الشعبية بين الشفهي والتدوين: قراءة تحليلية. “الذاكرة 8(1):165-178.

أقبوش، ادريس. 2020. ”الحكاية الشعبية الأمازيغية ودورها في تنمية القيم ”حكاية القنفذ والذئب نموذجا“. “الذاكرة 8(1):97-117.

الشاذلي، مصطفى، و محمد الداهي. 2009. ”الحكاية الشعبية في حوض البحر الأبيض المتوسط. “ الثقافة الشعبية 2(5):60-79.

شريّط، سنوسي. 2024. ”الأسطورة وسردية الحكي في رواية ”التِّبر “ لإبراهيم الكوني. “دليل الآداب و اللغات 3(1): 9-27.

Footnotes

[1] “هذه الأساطير ليست من تأليف كاتب، إذ هل تؤلف الأسطورة؟... لكن إذا كان لا بد للفعل من فاعل ما فإن الفاعل - أي المؤلف أو القائل–هو الشعب”

Extracted from the book by Said Sifaw important literary works in Arabic titled “أصوات منتصف الليل” (“The Voices of Midnight”), a collection of ancient Amazigh tales translated into Arabic. For additional information, please refer to the provided citation, which can be accessed via the following archived web link: https://archive.org/details/Aswat/mode/2up.

[2] An academic paper has been published that presents a comparative study analogous to the current discussion, starting instead, however, with China’s traditional Cinderella narrative. See, Wang and Hu, “Similar archetypes and different narratives.”

[3] In the majority of Idraren n Infusen region, the term ‘Tawessart’ (singular) or ‘Tiwessarin’ (plural) is predominantly employed to denote an elderly woman. Conversely, in other Amazigh-speaking communities located in Tripolitania, such as Ghadames with their variant called Taɣdimst, the term ‘Tameqqert’ (singular) or ‘Temeqqarin’ (plural) is used to characterize an elderly woman. Furthermore, in the Kabyle region of Algeria, the words ‘Taḍeggʷalt’ or ‘Tamɣaṛt’ are commonly used, see (Calassanti-Motylinski 1898); (Lanfry 2011); (Dallet 1972).

[4] Different terminologies are employed for the term tales across various regions in Tamazgha. For instance, in the Kabyle region, the terms ‘Amacahu’ and ‘Tamacahut’ are used. However, in the region of Idraren n Infusen, regional variations are observed. In the Fessaṭu region, the term ‘Tsisaw’ is used to denote a tale, whereas in Ifran and Zwara, the term ‘Tanfust’ (singular) or ‘Tinfas’ (plural) is preferred. These terms are variants of Tanfusit/Tayefrnit in the Tamazight language. Also, in the variant Taɣdimst, in the oasis of Ghadames, Libya, the words ‘Tullizt,’ ‘Tullist,’ ‘Tulliss’ (Singular) and ‘Tullizin’ (plural) are used for a tale or a story. See (Calassanti-Motylinski, 1898); (Lanfry 2011); (Dallet 1972).

[5] Arabization in Tripolitania after the spread of Islam took centuries, and it had an impact on Idraren n Infusen, where most of the oral tradition gradually vanished due to religious aspects. As described by Sahli, the Arabization came in waves: “Then a new wave of Moslem Arabs swept all over North Africa, and the final process of Islamization and Arabization of the Berbers extended to Black Africa at the Saharan southern edge.” Omar Sahli, Nafousa Berber Community in Western Libya, B.A. University of Libya, 1959.

[6] “Il Berbero Nefûsi di Fassâṭo. Grammatica, testi raccolti dalla viva voce, vocabolarietti,” by Francesco Beguinot, provides an exhaustive exploration of the Tanfusit variant of the Tamazight language, as spoken in the Fessaṭu region of Idraren n Infusen. This book includes a selection of intriguing ancient tales that have been meticulously documented.

[7] In his publication, Othman Kaak refers to a historical figure from the Rustamid Dynasty named أبو سهل الفارسي النفوسي. This individual served as a Tamazight interpreter during the Rustamid Dynasty and was the author of a poetry anthology in the Tamazight language. Regrettably, no remnants of this invaluable work have survived due to a conflict in the region involving the Nukkar movement, which resulted in the destruction of the anthology. Please refer to Kaak for more details.

[8] In the town of Ifran/Yefren, as well as in other towns within the Idraren n Infusen region, it is possible to encounter this tale of “Tafunast n Igujilen.” Intriguingly, this narrative bears a striking resemblance to a tale that is widely recognized within the Kabyle region of Algeria. Please refer to the citation provided for further details. https://www.hcamazighite.dz/docs/document/hca/Litterature-traduction/01%20Idlisen-nnegh/040-Nadia%20Benmouhoub.pdf

[9] Typically, narratives commence with introductory remarks, as observed in the region of Idraren n Infusen, specifically in Fessaṭu. It is customary for the elderly women of the community to initiate the storytelling process. The traditional opening phrase they employ is as follows: ‘Tsisaw d Tmilaw Bazin Yeḥlaw dis Tigerwaw.’ This phrase can be translated as: ‘Tales & riddles, a tasty stew with mushrooms.’

The information presented has been derived from a noteworthy article by Asil. This article is part of a series focusing on ancient tales, which was published on the website Tawalt.com during the 2000s. For additional information and context, please refer to the provided citation, which can be accessed via the following archived web link:

[10] Asil, a distinguished contributor to the Tawalt website, has written a collection of blog posts that delve into the ancient Amazigh tales from the Idraren n Infusen region. In one of her posts, she highlights the metamorphoses present in these ancient tales, such as the origins of certain plants, trees, and animals that were once humans and then transformed. For further reading, please refer to the following archived link: https://web.archive.org/web/20071017140513/http://tawalt.com/letter_display.cfm?lg=_tz&ID=2311.

[11] In the town of Ifran/Yefren in Idraren n Infusen, this type of owl is referred to as ‘Ajṭiṭ n ḍeggiṭ,’ which translates to "Bird of the Night." This owl is known by various names or similar variants across the region. In Tunisia, a similar tale refers to it as “النعوشة” or “أم الذراري,” while in Algeria, it is called “تانعوشت/Tanεuct,” akin to the name we use in Idraren n Infusen. This species of owl is large and is likely the Pharaoh Eagle-Owl, which inhabits many areas within the Tamazgha region. See, "النعوشة" أو "أم الذراري".. طائر الموت في الموروث الشعبي التونسي جزايرس : تانعوشت خطافة الأطفال; 2 Species of Owls Found in Libya! (2024) - Bird Watching HQ

[12] Given that the Tawalt webpage has been inaccessible for several years, the sole method for retrieving prior posts is via the Internet Archive. The following URL provides access to a specific archived post: https://web.archive.org/web/20110606061045/http://www.tawalt.com/?p=3840.

[13] The narrative of “Iɣed n Tinnurt” finds its roots in the town of Ifran/Yefren, where the local populace communicates in a distinct dialect of Tamazight, referred to as Tayefrnit. This dialect bears similarities to Tanfusit, another variant of Tamazight prevalent in different regions of Idraren n Infusen (Nefusa Mountains). For a more comprehensive understanding of the Tayefrnit variant, please refer to the book published by The Libyan Center for Tamazight Studies in Tripoli, titled “اللغة الامازيغية (الفواعد النحوية – تنوع جبل يفرن).” The book can be accessed via the following link: https://tamazight.edu.ly/2022/05/17/%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%84%d8%ba%d8%a9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%a7%d9%85%d8%a7%d8%b2%d9%8a%d8%ba%d9%8a%d8%a9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%81%d9%88%d8%a7%d8%b9%d8%af-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%86%d8%ad%d9%88%d9%8a%d8%a9-%d8%aa%d9%86%d9%88/.

[14] Recently, I have been fortunate to obtain access to an extensive library of audio recordings that comprise a collection of ancient Amazigh tales originating from Ifran/Yefren. Among these, I was privileged to discover a recording of “Iɣed n Tinnurt,” narrated by an elderly woman named Ghalya Shihub, from the village of At-Uɣasru. Regrettably, it was challenging to ascertain the exact year of the recording. Interestingly, this version of “Iɣed n Tinnurt” bears a striking resemblance to the rendition collected by Mr. Shnaib.

[15] Asil published notable posts on ancient tales from Fessaṭu and other towns in the region of Idraren n Infusen, emphasizing the widespread similarities among the tales that resonate across various locations within the mountains. For further reading, see:

https://web.archive.org/web/20071017140419/http://tawalt.com/letter_display.cfm?lg=_tz&ID=1831.

[16] In the narrative of “Ighed n Tinnurt,” the two sisters are characterized as voracious eaters. The original text, “Sent sis-net tidusay-n-sent timeqqrarin, welli a-t-ḥuṭ tameṭṭut n bab-n-sent xugga-net, d aysum d waɣi d tini, mi teǧa-net cra,” can be translated as follows: “The two elder sisters, known for their hearty appetites, would voraciously consume all that was offered to them—meat, milk, dates—leaving nothing behind.”

[17] This traditional headgear is donned across the expanse of Idraren n Infusen (Nefusa Mountains) and various locales within Tripolitania. In the region of Ifran/Yefren, alternative terminologies such as “Akabbus” or “Akembus” are employed to refer to this cap.

[18] In “Iɣed n Tinnurt,” the protagonist becomes aware of her father’s intention to abandon them after he sends all three daughters into the water well. As she prepares to descend into the well herself, she addresses her father with the following words: “tewwa-yas a baba essen-ɣak maεatec texs-ed-a-neɣ d texs-ed a-t-teftuk-ed seg-d-neɣ.” This phrase can be translated as: “She then addressed her father, ‘I am aware that you do not wish to keep us and would prefer to be rid of us.’”

[19] “The source of Grimms’ version of the story is unclear. It is thought that the original 1812 version came from a woman in a nursing home in Marburg (Rölleke 1975). “Grimm’s Cinderella Notes.” Virginia Commonwealth University. Accessed at: https://archive.vcu.edu/germanstories/grimm/cinder_notes.html.

[20] In the tale “Iɣed n Tinnurt” the protagonist, referred to Iɣed n Tinnurt, is portrayed as a person of forgiveness. Despite the adverse treatment she receives from her elder sisters, she exhibits an extraordinary ability to forgive. This act of forgiveness is a significant aspect of her character development within the story.

[21] In the narrative, the phrase ‘emmis n ṣṣulṭan’ is used to depict the son of the sultan. In the Tayefrnit variant of Tamazight, ‘emmis’ translates to ‘son,’ ‘n’ signifies ‘of,’ and ‘ṣṣulṭan’ corresponds to ‘sultan.’

[22] The term ‘Terlik,’ used in the region of Idraren n Infusen, is also pronounced as ‘Tellik’ in the Tamazight variant Taɣdimst, in the oasis of Ghadames, Libya. This term is derived from the name of a traditional type of footwear that is widely recognized in Ghadames, see (Lanfry 2011).

[23] Further details can be found in:

Bar-Itzhak, Haya. “‘Smeda Rmeda Who Destroys Her Luck with Her Own Hands’: A Jewish Moroccan Cinderella Tale in an Israeli Context.” Journal of Folklore Research 30, no. 2/3 (1993): 93–125. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3814312.

[24] Stachtopouta, from the Greek word stachti = ashes, which is a compound word that literally translates to "Ash-girl" or "Girl of the Ashes." Further details can be found in:

Marianthi Kaplanoglou (2016) Spinning and Cannibalism in the Greek ‘Cinderella’: Symbolic Analogies in Folktale and Myth, Folklore, 127:1, 1-25, DOI: 10.1080/0015587X.2015.1093821.

[25] For “Cenerentola,” the name is derived from the Italian word ‘cenere,’ meaning ‘ash’ or ‘cinder,’ while the protagonist's name in the tale is Zezolla. For further details, see Giambattista Basile’s The Pentamerone, or The Story of Stories. Translated by John Edward Taylor. Second Edition. London: David Bogue, 1850.

[26] In most Tamazight variants found in Idraren n Infusen, encompassing both Tanfusit and Tayefrnit, the term ‘Iɣed’ is predominantly employed to denote ‘Ash.’ Concurrently, the term ‘Tinnurt,’ signifying ‘hearth,’ is ubiquitously used across all regions of Idraren n Infusen. Intriguingly, in the Taɣdimst variant the term for ‘ash’ is referred to as ‘Iced’ while the term “hearth” is referred to as ‘Elkanun’.

-Lanfry (Jacques). Dictionnaire de berbère libyen (Ghadamès). Préface de Lionel Galand, Algeria, 2011.

[27] In the tale, the themes of resilience and rebirth are manifested through the survival of her sisters, a feat made possible by Iɣed n Tinnurt's clandestine provision of food. Furthermore, the demise of Tergu (the ogress) marks not only the end of a period but also the commencement of a new chapter in Iɣed n Tinnurt's journey. The rebirth is symbolized by her entry into matrimony, signifying the start of a transformative journey for her.

[28] Syed Rafid Kabir, "Vesta: The Roman Goddess of the Home and the Hearth,” History Cooperative, November 23, 2022, https://historycooperative.org/vesta-goddess/.

[29] Interestingly, we see a similar approach mentioned by Kaplanoglou in her study, which highlights Nicole Belmont's interpretation of the Greek Cinderella “Stachtopouta” as a figure close to Hestia, the Greek goddess of hearth (Kaplanoglou, 2016, P7).

Nicole Belmont is a French anthropologist specializing in oral tradition (tales and folklore). Further details can be found at: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicole_Belmont

[30] In both narratives, we observe a striking similarity in the protagonists’ experiences, particularly in relation to the death of their mothers. This significant event occurs at the outset of each tale, preceding the journeys of both “Iɣed n Tinnurt” and “Aschenputtel”, which ultimately culminate in marriage. From an analytical standpoint, one could argue that these marriages symbolize the continuation of their maternal lineage (further research appears to be necessary in this area for more explanation).

The Jewish Cinderella tale of “Smeda Rmeda” echoes this theme, where the protagonist proactively and discreetly seeks a spouse (Bar-Itzhak & Shenhar, 1993, P22).

[31] The text used in the context of this study has been derived from the collection by the Grimm Brothers:

Household Stories from the Collection of the Bros. Grimm, translated by Lucy Crane, Macmillan & Co., London, 1922.

[32] ibid.

[33] The presence of a character, either a sultan or the sultan’s son, is observed in some of the ancient Amazigh tales from Idraren n Infusen. Interestingly, there is an absence of any discernible traces of a prince, king, or queen. This phenomenon could potentially be attributed to the influence from the Ottoman Empire during its early or late stages or even during the Hafsid Dynasty in the region.

[34] From Ghadames, these slippers are recognized for their distinctive characteristic of being laminated in silver. For additional information, see Alberini, 1999.

[35] The following text has been extracted from the tale:

‘Ass seg ussan yus-ed emmis n ṣṣulṭan d yesseswa tagmart-nnes g tanut lli teǧǧa dis Terlik-nnes. Cwayya tagmart teqqim tetεayaf mi tuba at-tesswa, yehwa il wafra din yufa g ammaṣ n waman Terlik.’

This can be translated as:

‘On a fateful day, the sultan’s son arrived at the well to water his horse, near where the silver slipper had been abandoned. The horse hesitated to drink, prompting the young man to inspect the pool, where he discovered the silver slipper submerged.’

[36] The following text has been extracted from the tale: ‘Yexwat d yewwa, neč lal n Terlik id lama at-aɣeɣ, ayed lli d ad nejfaɣ sis.’ This can be translated as: “Retrieving it, he declared, ‘The lady to whom this slipper belongs shall become my bride.’

[37] The term ‘Aberraḥ’ is used across all variants found in the region of Idraren n Infusen. Interestingly, the same term, with an identical meaning, is also found in the Tamazight variant Taɣdimst of Ghadames. It signifies ‘proclamation’ or refers to someone who holds the responsibility of oral publication (Lanfry, 2011).

[38] In the narrative, the term ‘Tmura’ is employed, which in the Tanfusit/Tayefrnit variant signifies ‘land’ or ‘country.’ This same term is also used in other regions of Idraren n Infusen, where it takes the form ‘Tamurt’ in the singular and ‘Temura’ or ‘Temurawin’ in the plural.

[39] The following text has been extracted from the tale:

‘Yugur il uɣasru-nnes d yiga aberraḥ yuc-as Terlik din d yewwa-yas enneṭ g tmura d seffɣ-i-yed lal n Terlik id.’

This can be translated as: “He returned to his castle and entrusted the silver slipper to a servant, instructing him, ‘Travel throughout the land and locate the lady to whom this silver slipper belongs.’

[40] The following text has been extracted from the tale: ‘D wwa-net mak d a-ten-semma weltma-t-nneɣ d wwa-net d a-ten-semma Iɣed n Tinnurt.’ This can be translated as: ‘The elder sisters pondered, ‘What moniker shall we bestow upon our youngest sibling?’ They named her ‘Iɣed n Tinnurt’ (Ash of Hearth).’

[41] From another perspective, in the ancient Mediterranean, silver is also associated with the moon and femininity.

“Sappho, a renowned poetess of the Ancient Greek civilization, often celebrated the equilibrium of night, ending the ‘garish day’ in her works. This could be seen as a reflection of the association of the moon (and by extension, silver) with femininity.”

Mike Streich, “Women in the Ancient Mediterranean World,” Short History, 2017, accessed May 29, 2024, https://www.shorthistory.org/ancient-civilizations/women-in-the-ancient-mediterranean-world/.

[42] Lfujret, a well-known type of Tamazight jewelry in the region of Idraren n Infusen, is traditionally made from silver. Silver holds significant importance for women in the Amazigh culture of this region. Some of the silver jewelry designs, such as Tawenza (a headdress ornament) and Temkellin (traditional earrings), feature a distinctive half-moon shape and the symbol of goddess Tanit (her symbolism is closely linked to the moon and fertility rites).

[43] Grimm Brothers, Household Stories from the Collection of the Bros. Grimm, translated by Lucy Crane, and published by London: Macmillan & Co., 1922.

[44] In the region of Idraren n Infusen, it is a common practice for people to place a cup or a small pot filled with water atop graves. This act serves a dual purpose. Firstly, it provides a source of hydration for the birds. Secondly, they believe it carries a profound symbolic significance, as birds are seen as representations of the human soul. People in the mountains refer to these birds in Tamazight as ‘Ajḍiḍ n baba Rebbi,’ which literally means ‘Bird of our father god.’ They are often symbolically associated with the representation of the soul (Roque, 2009).

[45] In Tayefrnit variant of Tamazight, the term ‘Tergu’ is employed to denote an ‘ogress’ (fem.). In various other regions of Idraren n Infusen, alternative terminologies such as ‘Amẓiw’ and ‘Tamẓa’ are used to refer to a ‘Monster or ‘Ogress.’ These terms bear a similar word used in the variant Taɣdimst found in the oasis of Ghadames to denote an ‘ogress,’ which include ‘Amẓiw’ (masc. singular), ‘Amẓiwen’ (mas. plural), ‘Tamẓa’ (fem. singular), and ‘Temẓiwin’ (fem. plural). In terms of an etymological perspective, both terms Amẓiw/Tamẓa and Tergu have, I believe, different meanings. Interestingly, this term was mentioned in Ibn Khaldoun’s book on Amazigh or Berber. Here is an excerpt from the book translated by Slane: ‘Alahem, cheikh de ces peuplades, avait été élevé par les soins de son prédécesseur, Omar, fils de Tamza. En langue berbère tamza signifie démon.’ This phrase can be translated as: ‘Alahem, sheikh of these tribes, had been brought up by the care of his predecessor, Omar, son of Tamza. In the Berber language, tamza means demon.’ See, Lanfry 2011; Ibn Khaldoun, 1856.

[46] The following text has been excerpted from the tale: ‘‘Assseg ussan tbucilt tanaεnuct trebbec din len tufa xuǧin.’ This can be translated as, ‘On one fateful day, the youngest girl unearthed a hidden cavity while digging.’

[47] In the narrative, the term used is ‘Amjer’; other variants pronounce it ‘Medjer.’ It is used to denote a sickle. This term is prevalent in all Tamazight variants in the region of Idraren n Infusen. The sickle holds significant symbolism in this context. Not only does it represent a tool used for harvesting wheat to produce flour, but it also embodies the power to enforce punishment and maintain control. See (Calassanti-Motylinski 1898).

[48] The protagonist's name in the Jewish Cinderella story “Smeda Rmeda,” reveals a captivating link between flour and ash. Judeo-Arabic storytellers translate “Smeda” as semolina flour and “Rmeda” as ashes (Bar-Itzhak and Shenharp, 1993, 90).

[49] This translates to ‘Jinn or human.’

[50] This translates to, ‘I am human, superior to both your father and mother.’

[51] The following text has been excerpted from the tale: ‘d tewwa-yas tergu atf-ed amig-aɣ d yelli.’ This can be translated as, “The ogress invited her inside, offering to adopt her. ‘I will make you my daughter.’”

[52] In the tale, “Iɣed n Tinnurt” tricks Tergu and this ends up getting her killed. This depiction emphasizes the vulnerability of the ogress, who can be fooled by the tales’ heroes or heroines, who thereby demonstrate their civilized superiority (Lacoste-Dujardin 2013).

[53] “In regards to metals, Tuaregs as a rule historically attributed the quality of impurity to gold and that of purity to silver. The preference of silver over gold is one that is evident for all Imazighen, Tuareg or Berber. In North Africa, as in Niger or Mali, Amazigh women treasure their silver jewelry and generally disdain gold” (Hagan and Myers 2006:91).

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 3 • Issue 1 • Spring 2025

Pages 4-22

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Tira for Research and Studies