Introduction

AUTHOR: TSJ Editors

Tamazgha Studies Journal Celebrates its First Year

Editors

It has been a little over a year since we launched TSJ in the fall of 2023. As we release this third issue, we want to take the opportunity to reflect upon our vision for the journal and the remarkable work we have had the honor to publish so far. Although short, this period has allowed us to solidify our vision for TSJ as an interdisciplinary and transregional platform that can create the conditions for the emergence of the kind of scholarship that proactively defies the dominant geocultural imagination, which has, for a very long time, designated North Africa and the Maghreb as the primary names for an important portion of Tamazgha. Our experience this year has confirmed our belief that Tamazgha, as a broader Indigenous space with deep historical and sociological ramifications, has much untapped scholarly potential. We can already see its emerging breadth in the contents of the first two issues, robust with scholarly articles, literary translations, personal reflections and interviews. Tamazgha, as an evolving and emerging socio-cultural milieu, remains our compass and the focus of our effort to broaden the scope of methodologies and critical questions that undergird the deployment of this concept. Our commitment to the study of Tamazgha aside, this year has taught us that there is more work to be done to reach the segments of the academic community which can produce the kind of scholarly works that will transcend the current disciplinary boundaries, which holds back students and emerging scholars from benefiting from the advantages Tamazgha offers. This area’s scholarly potential can only be unlocked when emerging scholars adopt and routinize Tamazgha.

In addition to tethering our attention to Tamazgha, we have worked to sustain and deepen the journal’s interdisciplinary approach to the study of knowledge production. In these first three issues, as editors, we have particularly welcomed interdisciplinary attention to topics such as identity, indigeneity, language, memory, gender, migration and the concept of space itself. We also have valorized the centrality and creativity of cultural production such as music, material culture, language and literature in Tamazghan production of knowledge. Looking forward, we reaffirm that the study of Tamazgha, with all the adjustments and changes that are entailed by its redrawing and expansion of the physical and conceptual boundaries of the current Maghreb/North Africa, places us at the heart of interdisciplinary approaches. Interdisciplinarity requires both awareness and criticism of the prohibitive limitations of the current Maghreb/North-Africa-dominated imagination. These limitations are deeply at odds with the emerging Amazigh indigenous consciousness and its remapping of the region under the umbrella name of Tamazgha, an open project which cannot be understood and deployed without building the capacity to work outside the comfort zone of Maghreb, North African or sub-Saharan African studies. In this regard, scholarship is confronted with the tough choice either to align its terminology and geographical appellations with those used by Indigenous people on the ground or to remain faithful to its time-tested practices, which have participated in entrenching nomenclatures that do not necessarily do justice to Indigenous worldviews. Our constant invitation of interdisciplinary and experimental projects emanates from our steadfast commitment to exploring the possible and not merely the permissible.

Again, cultural production, and specifically literature, has been one of the fronts in which a Tamazgha-focused scholarship can push the boundaries of the scholarly possible in this space. The vulgate that the literature of the northern part of Tamazgha (Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia) was solely produced in French and Arabic has outlived its course. The past forty years have witnessed a phenomenal rise in literature in both Tamazight and Darija, but the extension of the powerful Arabic-Francophone hegemony into the slowly changing academic discussions has sustained the misconception that cultural production in the region is written either in Arabic or French. The reality is, of course, different and defies any reductive binaries. In this regard, Matthew Brauer’s article in this issue, entitled “More than Arabic or French: Language, Land, and the Making of the Postcolonial Novel in Tamazgha” makes an important contribution to Tamazghan literary history by complicating the genesis of the novel and rethinking the prevalent binaries. Through his meticulous analysis, Brauer repositions Tamazight and its literature at the heart of the conversation on Tamazghan literatures. Again in the literary vein, Mazigh Buzakhar’s article “A Tale of Two Cultures: Comparative study of ‘Iɣed n Tinnurt’ from Infusen and ‘Aschenputtel’ from Germany” provides crucial insights into Amazigh art of storytelling in the Idrarn n Infusn in Libya through a study of oral tales in Tamazight and German. Adopting a comparative approach, Buzakhar traces the emergence of these tales in Tamazight and their manifestation in German texts, contextualizing everything in a longer literary history in Tamazight. Finally, Abdessamad Binaoui and Mohammed Moubtassime’s article “Translatability of Tamazight songs into English (Case study: famous songs by the Moroccan singer Mohamed Rouicha)” examines both the potential and the limitations of translation from Tamazight into English. Rich and perceptive, this article draws on the songs of the late Amazigh singer Mohamed Rouicha to convey the challenges of translating between two asymmetrical languages. Together these three peer-reviewed articles center Tamazight as an object of novelistic output, storytelling, and translation theory.

Likewise, Amazigh music has witnessed a remarkable renewal since the 1970s. A new generation of male and female singers has modernized both the music and its themes for a variety of societal, cultural, and political engagements. There is also an increasing number of Amazigh singers who sing alone or in duets, which opens up space for new thematic and performative innovations. Ella Williams’s peer-reviewed article “Amazigh Women’s Agency: Exploring the Gendered Aspects of Amazigh Linguistic and Cultural Transmission through Contemporary Tachelhit Pop Songs” combines the discussion of gender and music in the Tashlḥīyt-speaking region. Drawing on Amazigh songs, Williams probes the intersection of “Amazigh women’s agency and the gendered aspects of Amazigh linguistic and cultural transmission through the case study of contemporary Tachelhit pop songs.” Williams contributes to a growing body of scholarship that focuses on the study of Amazigh music and its themes. Broadening the scope of Amazigh musical scenes and revealing its transnational underpinnings, Airy Dominguez’s article “Sounds of Identity and Resistance: A Journey Through Amazigh Music” demonstrates the multiplicity and the creativity of Amazigh musics. Originally published in Spanish, this article, which we reprint here in translation, is a genealogical map of the emergence, transformation, and continuity of different Amazigh musical styles between the 1970s and the present-day.

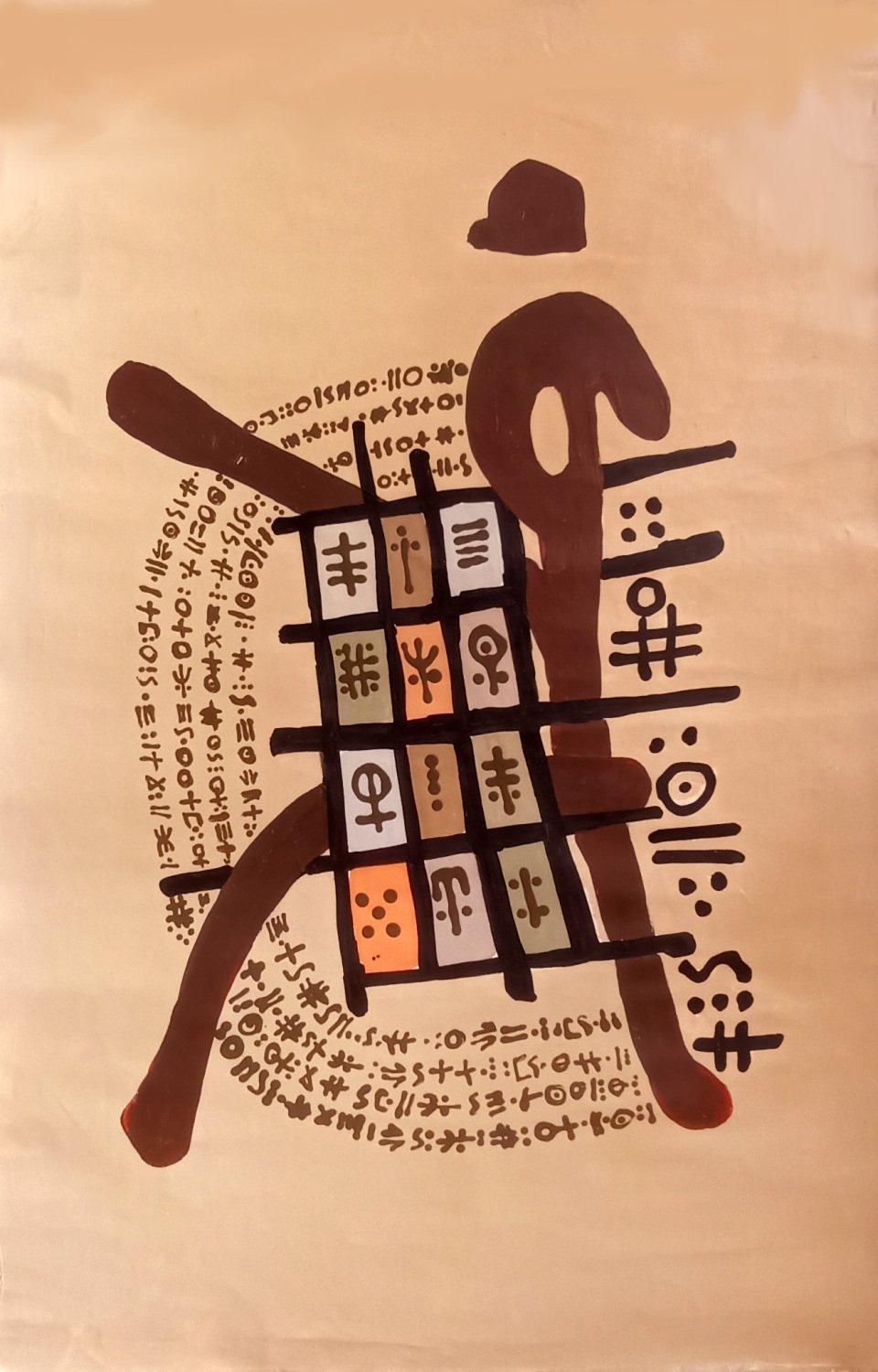

This issue features a contribution by Abdellah El Haloui on the Amazigh rock inscriptions also known as the Lybico-Berber script. Entitled “A Geocontourglyph for Gypsum in Sidi Jafaar,” El Haloui’s study focuses on an ancient word that was found on a rock in the Ouarzazate area. We have placed this groundbreaking article into a new category for the journal: New Directions. With this category, we affirm the journal’s commitment to new methodologies and experimental work that is not easily peer-reviewed due to a lack of established expertise, but that has the potential to build new directions in scholarship. El Haloui’s article has not been assessed by other colleagues in the field for the simple reason that we were unable to find reviewers who felt comfortable evaluating an article that advances interpretations about the lesser-known ancient period. However, we decided that the interpretations El Haloui is advancing should be published to help build this expertise and renew the conversation about the study and interpretation of ancient Amazigh inscriptions. We warmly invite other scholars who work on this period, or in other less-frequently studied areas, to submit their work to TSJ.

The issue also features an interview with Madghis M. Madi about the Tawalt platform. Madghis founded Tawalt in the early 2000s to support the cultural and linguistic revival in Libya and Tamazgha, and the website has since become an unavoidable resource for those interested in all manners of Amazigh heritage. Tawalt, and Madghis by extension, has played a crucial role in connecting Amazigh youth throughout Tamazgha to their cultural roots thanks to its multiple publications and online resources. This interview is a celebration of Tawalt’s success and an opportunity to dialogue with its founder to shed more light on the platform’s origins and current evolution.

Faithful to our commitment to literary translation and broadening access to Tamazight literature to non-Tamazight speakers, this issue features two translations by Ali Abdeddine and Adelie Block. The first poem is entitled “Aẓnāg” by Taieb Amgroud, who is one of the most gifted poets in Tamazight. The second poem is entitled “Sawl fīss” by Mohammed Moustaoui, another peak of the Amazigh poetic tradition. Poetry is not just overly represented in Amazigh literature, but it is the literary genre that most comes to mind when we think about anything Imazighen do to celebrate their existence. These two poets’ output particularly deserve multiple translations. They have produced a momentous body of poetic collections that need a more systematic effort to make them available in English.

As we make this issue available to our readership, we also would like to share one of the lessons we learned from our first year of existence as a journal. Our editorial work has helped us gain awareness of the many challenges that face open-access journals, particularly in their endeavor to attract submissions from contributors who are used to equating scholarly prestige with traditional venues. It has been edifying to learn that we need to do more work to reach out potential writers through programmatic initiatives that would increase submissions. It is not sufficient that we started a journal that openly invites contributions; we also need to undo an entire set of practices that have hampered the unlimited possibilities offered by open access. As a result of this awareness, in the near future TSJ will sponsor several thematic events, both online and in person, to consolidate the link between the venue, scholars and cultural producers.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 3 • Issue 1 • Spring 2025

Pages 1-3

Language: English