Tamazgha Guest

Tamazight is a Literary Language: Interview with Mohamed Nedali

AUTHOR: Brahim El Guabli

Tamazight is a Literary Language: Interview with Mohamed Nedali

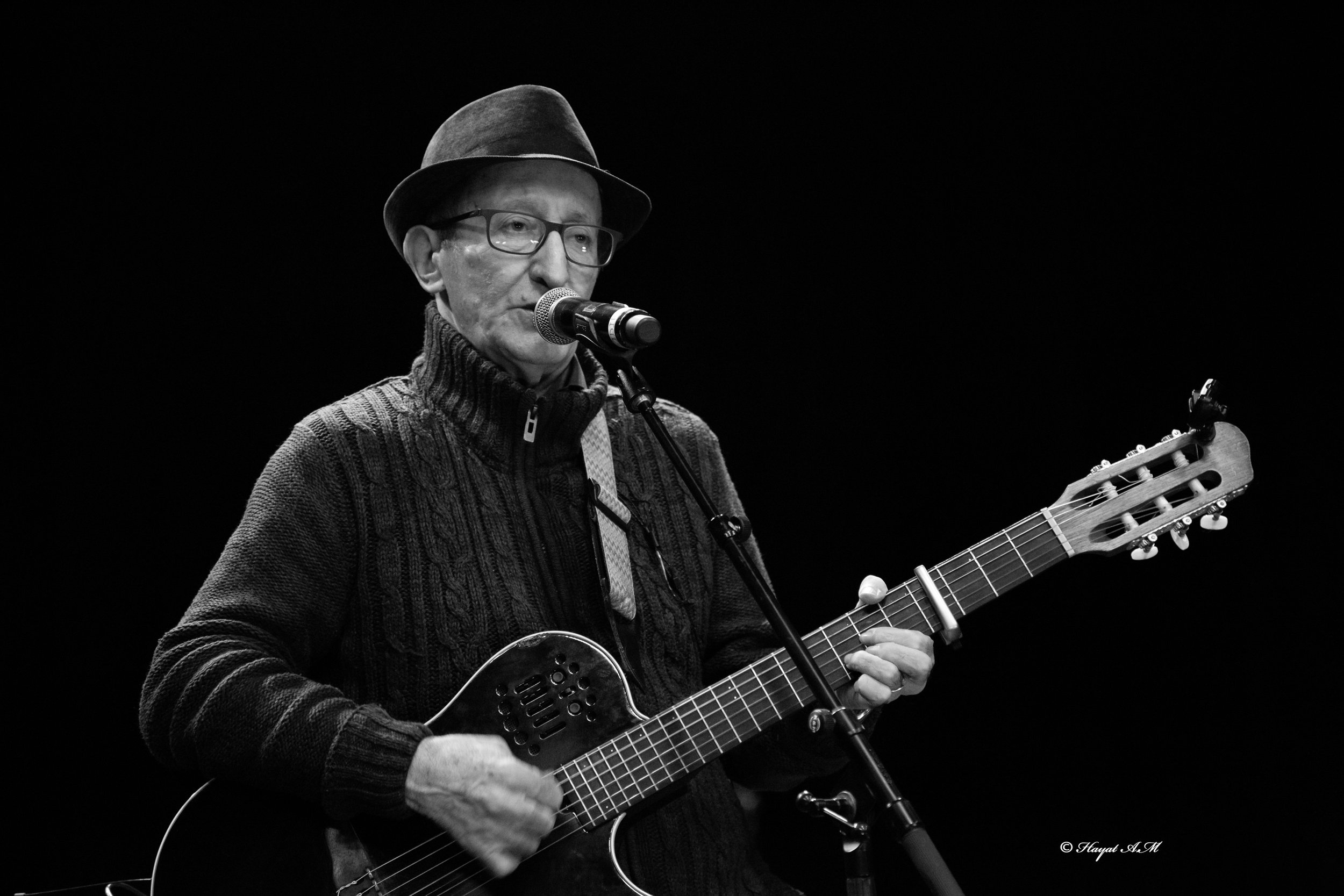

Mohamed Nedali

Brahim El Guabli

Williams College

Mohamed Nedali is a renowned Moroccan novelist who writes and publishes in French. This Amazigh novelist, like many writers from Tamazgha, has made major contributions to Francophone literature, and his award-winning books are the object numerous academic studies. However, at the height of his literary success in French, announced the publication of two books in Tamazight in May 2024. Of course, gifted writers switch languages and are able to move deftly between different idioms. Algerian authors Amin Zaoui and Rachid Boudjedra write their literature in both Arabic and French, which serve as literary homes for them. However, both Arabic and French are widespread languages that offer significant opportunities in terms of visibility and readership. Moreover, they are now routinized languages between which there is an important traffic of translation, particularly for established authors whose works can be easily picked up by publishers to be translated from Arabic into French or vice versa. Nedali’s decision to write literature in Tamazight after establishing himself in French is nothing like switching between Arabic and French.

Nedali’s move is “Ngũgĩan” in nature. It reminds us of Kenyan novelist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o’s decision to leave writing English and write in his mother tongue of Gikuyu. The similarities and the parallels between the choices of the two authors are clear despite the fact that one left English forever while the other’s relationship to French remains. First, both of them made the switch after attaining recognition in a language inherited from colonialization. Second, both Gikuyu and Tamazight are indigenous languages, which means that the authors are aware of the self-demotion that is encoded in the decision to switch from writing in English or French to producing creative writing in local languages that do not possess or offer the same prestige, resources or marketing opportunities. Third, these two authors understand the career risks that emanate from writing in the mother tongue. It takes the successful writer’s commitment to their mother tongue to embrace it as the language of their literary output. For Ngũgĩ, this commitment came from the importance of local languages for his understanding of decolonization while for Nedali it seems that the return to the mother tongue is urged by a desire to contribute to the revitalization and rehabilitation of Amazigh language and culture.

In his famous book Decolonizing the Mind, Ngũgĩ included a statement in which he bade “farewell to English as a vehicle for any of [his] writings,” announcing that “[f]rom now on it is Gikuyu and Kiswahili all the way.”[1] Ngũgĩ’s announcement was of the most important transformative shifts that split the temporality of post-colonial African literary history into pre-Ngũgĩ and post-Ngũgĩ eras. After this Ngũgĩan intervention, the relationship to African languages was never the same. Colonial languages, which became indigenized in the postcolonial period, were no longer taken for granted as the only avenue toward literary success. Moreover, their dominant-dominated relationship with indigenous African languages elicited more critical reflection. Although Nedali’s has not indicated any forsaking of writing in French, which should not be an expectation in anyway given the changes that have happened in the literary field since 1980s, Ngũgĩ’s renunciation of writing in English paved the path for generations of writers to reembrace their mother tongues and revolutionize their literatures. Even though he does not receive credit for it, this Ngũgĩan linguistic rebellion must be placed among the factors that inspired the re-indigenizing revolution that Amazigh youth have carried out in the last forty years to revitalize their language by constructing an Amazigh literary field.[2] Does not Ngũgĩ speak for every Amazigh child when he writes that at school he discovered that the “language of [his] education was no longer the language of [his] culture.”[3] The process of deculturation through the erasure of the mother tongue, which school made no longer relevant for education and social promotion, is a common aspect of postcolonial societies where indigenous languages became devalued compared to colonial-era languages.

Nedali’s expansion of literary language to Tamazight is not fortuitous. As he reveals in this interview, he is an engaged reader of Amazigh writers. His literary worlds in French are anchored in his Amazigh language and culture. After all, a writer who writers in a language other than their mother tongue does not come from a void; they are the product of a society, a language, and a worldview that inhabit and even haunt their words their literary foreign language. Nedali demonstrates that Amazigh language is not just a spoken language but rather a carrier of a millennial civilization that has fallen off the radar of its own people. Therefore, his embrace of Tamazight as a language of writing is not a frivolity but as he says “a duty.” Imazighen, a people who, given their very location in the nexus space of Tamazgha, have been positioned to be cultural and linguistic mediators between different civilizational spheres. They have played this role impeccably and contributed to different literary traditions, be they written in Latin, French, Arabic or Spanish. However, their literary creativity rarely found its way back into their own language. This situation has changed, however, thanks to the work of the Amazigh Cultural Movement (ACM). The ACM’s work in the forty years has achieved one of the most transformative feats in Amazigh literary and intellectual history, capturing the vibrancy and liveliness of Amazigh cultural production. As Nedali says, the increasingly rich literary corpus that the ACM’s initiatives have produced demonstrate that “Tamazight has absolutely nothing to envy the most used languages in this world and that it lends itself perfectly to literary creation.”

Brahim El Guabli (B.E): You have built over the years a very engaged Francophone readership; but, recently, against all expectations, you announced the publication of two novels in Tamazight. Could you tell us a little more about this return to the mother tongue?

Mohamed Nedali (M.N): The idea of writing in Tamazight, my mother tongue, dates back to about ten years ago, when I discovered the Amazigh literature of the pioneers, such as Ali Ikken’s Asekkif n inzaden (The Soup of Yarn), which was published in 1994 and was awarded the Mouloud Mammeri literary prize, and Mohamed Akounad’s novella entitled Tawargit d imik (A Dream and a Little More), which is translated into French by Lehcen Nachef under the title Un you-you dans la mosquée (A Trill in the Mosque)… I said to myself: “One day or another, I have to add my stone to the edifice.” A few years later, I began to take a close interest in this literature, then I learned Tifinagh, the Tamazight spelling, as well as its syntax. At the beginning of 2021, I began writing my first text, a story entitled Azemz n tinml (School Days) in which I recount my first year at the village school. What a pleasure to narrate your school life in your mother tongue! In 2022, I signed the publishing contract with IRCAM, the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture. Since then, I have been waiting for its publication. Last year, I wrote my second novel in Tamazight, Tizi n Tghawsiwine (The Time of Things), which I submitted to Tirra, the Alliance of Amazigh Writers, based in Agadir. Tirra published the novel in April 2024 and made it available for purchase during the Rabat International Book and Publishing Fair (SIEL 2024). Readers' interest in the work was such that the book was quickly out of stock.

B.E: Your journey is the opposite extreme of that of most of the writers of what is commonly called the Global South. As a general rule, authors seek to be translated or even to write in more widespread foreign languages, while you, a writer already renowned among French-speaking readers, have made the decision to write in Tamazight. What is your motivation?

M.N: The love of this magnificent language that is Tamazight. All the linguists who have studied it say it: it is a marvelous language, one of the most beautiful in the world. In addition to being rich, expressive, colorful, harmonious, poetic and easy to learn, it carries within it a wind of freedom and emancipation, which our society greatly needs in these times where obscurantism and stupidity are in full swing. More than a language, Tamazight is a treasure that conceals many wonders.

As for Amazigh culture, it is of undeniable richness and finesse. The Amazighs excelled in almost all the arts: architecture, pottery, cooking, sewing, embroidery, poetry, singing, dancing... Their law are a testament to a profound intelligence and understanding. You just have to read azerf (the Amazigh customary law) to realize how far Imazighen were ahead of other peoples, including Westerners. I was amazed to discover, for example, that prison did not exist among Imazighen, that they did not apply the death penalty either, that men and women were equal in rights and duties; that women could access all positions of responsibility, including that of head of state or even serving as a leader during war...

B.E: The words you used to announce the publication of your novel are full of emotion. As I looked through them, I felt a sense of liberation and an intense bond of kinship.

M.N: I received many reactions from Amazighs, from the country and from the diaspora, along the same lines. These words published on my FB page to announce the publication of my first novel in Tamazight, indeed described a true emotion, so they deeply touched the readers, more particularly the Amazigh speakers among them.

It must be said that I had a lot of trouble writing these two books in Tamazight, particularly because there is no Amazigh keyboard. The process was slow and painful: I typed my sentence on the IRCAM online keyboard, selected it then pasted it into the word document, painstaking work that required a lot of patience and just as much tenacity. Still, at the end, when the book is finished, the emotion I felt simply has been unequaled in my journey as a writer.

B.E: I imagine that your literary commitment to the Amazigh language is not new. Can you tell us a little about your literary and cultural relationship with the Amazigh language?

M.N: It is the relationship between a child and his mother, when she is thoughtful and loving. Amazigh culture and language have always been my main source of inspiration. My stories very often take place in remote villages of the High Atlas. This is the case in Le Bonheur des moineaux (The Happiness of Sparrows), La Maison de Cicine (Cicine’s House), La Bouteille au cafard (The Cockroach Bottle) … My characters, main and secondary, are almost always Amazigh, or of Amazigh origin. While writing in French, I actually never stop writing in Tamazight. One of my readers once told me in public: “When reading you in French, Mr. Nedali, I have the impression of hearing an Amazigh voice telling me the story as it goes along.”

That said, I owe my first literary sensitivity essentially to my mother tongue. As a child, I heard people around me singing the texts of the great ancient as well as modern imdyazen (poets). My parents and grandparents told me wonderful Amazigh tales... It must be said that I am lucky to be born in an environment where well-spoken words are valuable. In the slightest exchange with them, they cited a phrase, a saying or a few lines of poetry. They were convinced that the quote reinforced their words and thus made them unassailable. This characteristic is a major asset for the writer that I would become later.

B.E: What do you hope to achieve by publishing these two novels. In the meantime, can you tell a little bit about Azemz n tinml?

M.N: Azemz n tinml (School Days) is a story the publication of which is IRCAM’s responsibility. The director of their Book Office told me last month that the novel will be published shortly, but “wait and see,” the English proverb says.

What do I hope by writing these two texts in Tamazight? To prove to my fellow citizens that Tamazight has absolutely nothing to envy the most used languages in this world and that it lends itself perfectly to literary creation.

That said, it should be noted that I wrote these two texts in a very simple language, accessible to all Amazigh readers, whatever their level, region and age. An Amazigh-speaking writer friend with whom I shared the typescript of the second book for proofreading made this remark to me: “Your novel is written in a simple language, but I must admit that it is an inaccessible simplicity.”

B.E: In the global context of indigeneity, literature serves as an ideal platform for cultural advocacy. How do you see the role that well-known Amazigh intellectuals and writers can play in the creation of an Amazigh aesthetic capable of contributing to the revitalization of this language and the culture it conveys?

M.N: More than a role, it is a duty. Amazigh writers and intellectuals, or those of Amazigh origins, have a duty to promote the genius of this language as well as the culture it conveys, each in their sphere of activity. To counter the religious obscurantism that regularly threatens our country, there is nothing better than the development of Amazigh culture with its founding values: freedom, equality, fraternity and respect for life. In this regard, I note with optimism that more and more Moroccan important figures are openly claiming their Amazigh identity: politicians, writers, intellectuals, artists, journalists, musicians, and athletes, among others. The Amazigh language and culture are, for Morocco and for other Maghrebi countries, an effective tool to combat Wahhabi and Muslim Brother obscurantism.

B.E: It goes without saying that translation is an essential tool in the transmission of ideas and aesthetic forms, but it can also constitute a major force for the regeneration of literature. Based on this principle, how can the translation of “world literature” contribute to the development of Amazigh literature?

M.N: Translation is undoubtedly a determining means in the regeneration and dissemination of literature, provided, however, that it is carried out by fine connoisseurs. Indeed, to translate a literary work well, it is not enough to master the source language and the target language; you must also, and above all, be passionate about literature, because meaning is as important as style. The ideal would be for the translation to be conducted by experienced writers and poets, because only a novelist is able to translate another novelist, only a poet is truly capable of translating another poet... The best translations of literary texts are those accomplished by writers and poets recognized as such: Edgar Allan Poe translated by Charles Baudelaire, Shakespeare's Hamlet translated by Voltaire, Oscar Wilde translated into Spanish by Borges, Mahmoud Darwish and Abdallah Zrika translated into French by Abdellatif Laâbi.

Footnotes:

[1] Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House, 1987), xiii.

[2] Brahim El Guabli, “Literature and Indigeneity: Amazigh Activists’ Construction of an Emerging Literary Field,” The Los Angeles Review of Books, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/literature-and-indigeneity-amazigh-activists-construction-of-an-emerging-literary-field/

[3] Ngũgĩ, Decolonising the Mind, 11.

How to Cite:

El Guabli, B., (2024) “Tamazight is a Literary Language: Interview with Mohamed Nedali”, Tamazgha Studies Journal 2(1), 106-110.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 2 • Issue 1 • Spring 2024

Pages 106-110

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Williams College