Homages

Idir in the Midwest of the US

AUTHOR: Alek Baylee Toumi

Idir in the Midwest of the US

Alek Baylee Toumi

University of Wisconsin, Stevens-Point

Abstract: Idir in the Midwest talks about how Algerian Kabyle singer Idir and Berber music came to be played on WORT radio station in Madison, WI, and in the Midwest of America. This is also a humble acknowledgment and tribute to Idir and the generation of modern Kabyle singers, such as Imazighen Imula, Yugurthen and the feminist band, Djurdjura, who followed on Idir’s footsteps.

Keywords: A Vava Inou va, Berber culture, Kabyle music, Resistance, Imazighen (Free men), Indians of North Africa.

On Saturday, May 2, 2020, the Berber singer Hamid Cheriet, known as Idir, passed away at the age of 70. The Kabyle singer and musician came from the village of At Lahcène, At Yenni in Kabylia, the largest Berber-speaking region in northeast Algeria.

Because of the Covid-19 pandemic in America, Spring 2020 was a very difficult semester from a professional point of view, as well as socially and intellectually. As a Professor of the French language and French and Francophone literatures at the University of Wisconsin Stevens-Point, I started by teaching my classes normally. But with the coronavirus spreading at such high speed, we had to change mid-March, right at the start of spring break, and teach the second half of the semester online. On Sunday, May 3, a week before the end of classes, I learned on the internet of the death of the singer Idir. Skeptical and quite suspicious, especially with the spread of fake news that had become constant on the internet, I contacted my old friend Hamid Djessas,[1] who confirmed the tragic news to me. Known in France, Europe, and Canada, Idir had less recognition in the United States—he had, however, been very well known throughout the 1980s in the Midwestern US, thanks to the radio station WORT in Madison, Wisconsin.

Flashback

In 1977, Idir’s 33 rpm album A Vava Inou va was sold—miraculously—in Algeria.[2] The following year, while an undergraduate student at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, I received this great album from a friend in Algiers, which arrived safe and sound. It wasn’t broken! After listening to it, many Algerians and Americans wanted a tape of the album and asked me to make a copy for them.[3] Jim Haas, an American friend of mine who was the host of the international music program On the Horizon on the commercial-free radio station WORT,[4] started by playing songs by Idir on the radio, notably A Vava Inou va, Ssendu, and Zwit Rwit. Some time after listening to the whole album and relistening to A Vava Inou va several times, he said to me:

I do not understand the lyrics, but the music is so beautiful, the way Idir plays the guitar and sings, then how the woman joins him ... It’s great, amazing!

Even if Jim Hass did not understand the lyrics of the Kabyle songs, he liked this “humble and noble” music, as he said, so much that he decided to use A Vava Inou va as a “theme song” to start On the Horizon. The show was then aired on the WORT radio station Monday through Friday, every evening at 5 p.m., which is dinner time in the US, when there are many listeners. Jim explained to his audience that Algeria was, of course, an Arab country, but that the natives—the first inhabitants—were the Berbers, and that their language and culture, more than two thousand years old, were different from the Arabic ones. And that this song A Vava Inou va was inspired by a Kabyle tale and that the title could mean My Father, the Protector. After six months, much of the University of Wisconsin, along with the city of Madison and surrounding areas, knew Idir through the program’s theme song. Listeners called regularly to ask if it was the soundtrack to a film and where they could get the album.

April 1980 and the Kabyle Spring

The ban on the Kabyle writer Mouloud Mammeri that prevented him from holding his conference on Ancient Kabyle Poetry was the spark that set off the powder kegon April 20, 1980.[5] A series of demonstrations and strikes began at the University of Tizi Ouzou, the capital of Great Kabylia. After that came the turn for the universities of Algiers, then all of Kabylia, to go on strike. The students demanded the recognition of the Berber language and culture, which had been declared forbidden to exist.[6] Another friend, Walter Lane, who hosted the political-historical program World Views on WORT, invited us to do a program on The Berbers: History, Language and Culture, and on the Berber people, whom he considered to be “the Native Indians of North Africa.”[7] One of the consequences of this movement for the safeguarding and promotion of Berber culture was the development of Kabyle music, with the emergence of new singers and modern music bands. By wanting to definitively erase Berber culture, Le Pouvoir ended up exploding it, like a time bomb that had been just waiting to go off for too long.

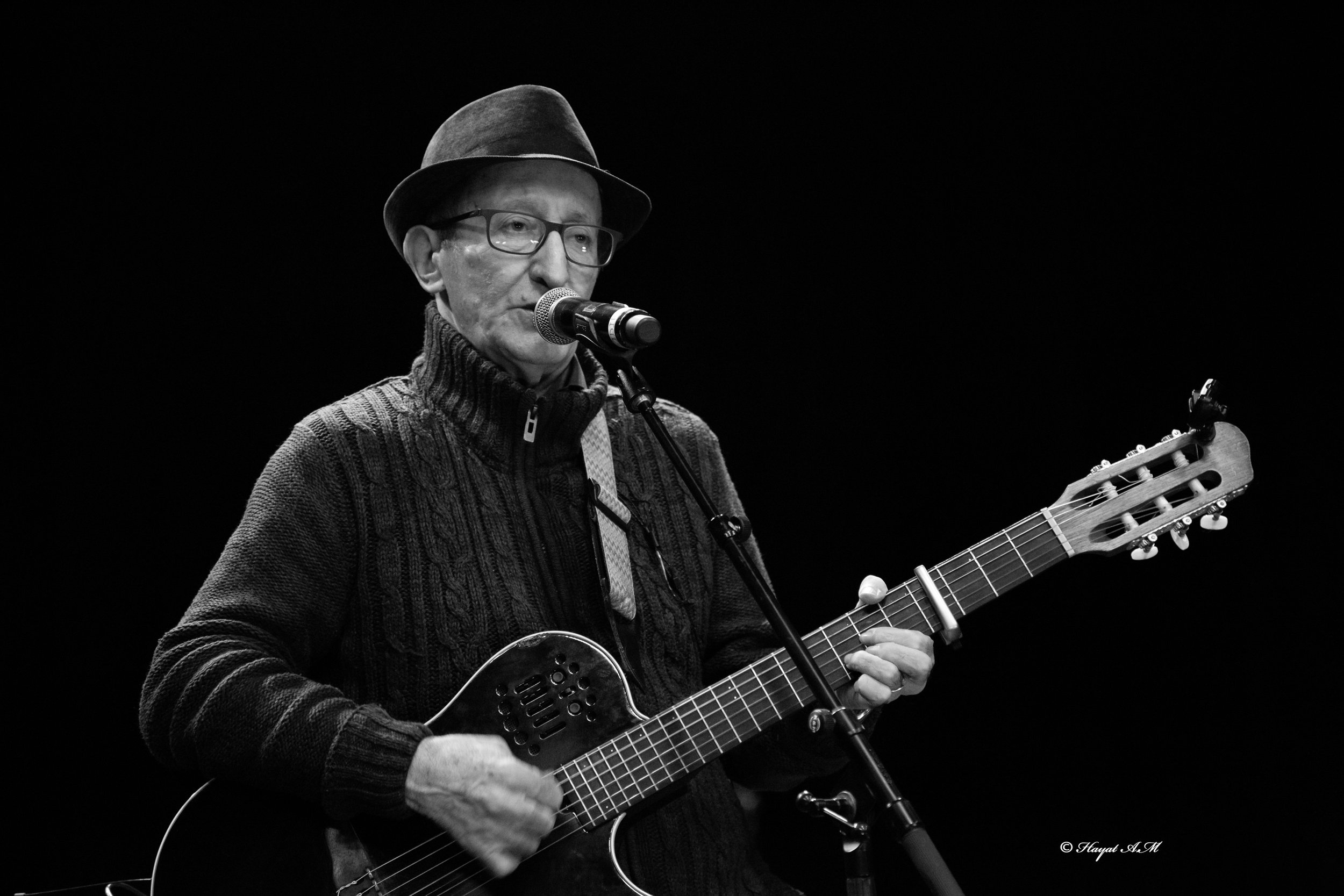

FIG. 1. Idir. Credit: Hayat Aït Menguellet

I was in Paris the following year, 1981, and made a pilgrimage to the little Editions Berbères bookstore at 11, rue de Lesdiguières. I bought a dozen Kabyle records—these included albums by Idir, Imazighen Imula, Yugurthen, Mennad, Djamel Allam, Djurdjura, Matoub Lounes, and Ait Menguellet. When I got back to Madison, I showed them to Jim, who asked me if I could lend them to him just one afternoon so he could professionally record them and then play them on his show on WORT. I did so with the utmost pleasure and gratitude! Jim also invited me to do a special show about Berber culture and the new type of Kabyle song. He’d chosen A Vava Inou va as the "theme song" to start his show because of his adoration for Idir. He had discovered and loved the Kabyle bands Imazighen Imula and Yugourthen, as well as the all-female band Djurdjura, which was very popular among feminists in Madison. It was probably thanks to Jim that a major Madison record store decided to contact their suppliers at World Records in Chicago and New York so as to order the Idir LP. It was with no small difficulty and after many tribulations that this record store succeeded in importing the album A Vava Inou va and selling it locally on State Street. Idir rose to prominence from the city of Madison to Chicago, IL and Minneapolis, MN.

With 45,000 students, the University of Wisconsin-Madison had one of the nation’s programs of international students and scholars—over 20%, or 10,000 people. The departments of French, African Literature, African Languages, and History were among the largest in the Midwest and the US.[8] In terms of literature, Algeria was known on campus thanks to two Francophone authors who had been translated into English: Albert Camus with The Stranger and The Plague, and Frantz Fanon with The Wretched of the Earth. In the field of music, it was Idir who, with his first album, had become the ambassador of Berber and Algerian culture to the Midwest.

For cultural activities on campus, the University of Wisconsin Memorial Union sometimes showed Algerian films like The Battle of Algiers by Gillo Pontecorvo, and Chronicles of the Years of Embers by Mohamed Lakhdar-Hamina would be presented by a History or African Studies professor. After the showing of films and/or to celebrate the end of the semester, a dinner was offered at one of these professors’ houses, where we served couscous with vegetables and listened to Idir. The guests danced to reggae music as well as to Idir’s Zwit Rwit. La maison française-French House of Madison sometimes had a “soirée africaine” (an African evening), which involved listening to Idir while eating good couscous[9]. Along with Bob Marley, Stevie Wonder, Fella, Manudi Bongo, and other African musicians, Idir had become one of the stars of these cultural activities.

If in the 80s Idir had disappeared from the scene in France, he had meanwhile become very present on the radio in the Midwestern United States. With time and the internet, his album A Vava Inou va, available on CD, immortalized Idir in America and elevated his music to the status of universal culture.

Footnotes:

[1] Hamid Djessas is from the same village as Idir in Ben Yenni. The late Mustapha Ourad, a proofreader at Charlie Hebdo magazine in Paris who was assassinated by Islamist terrorists in 2015, also came from the same village. Djessas, Ourad, and I were all together at the French Catholic boarding school College des Pères-Blancs, Lavigerie, El-Harrach, Algiers in the 60s-70s.

[2] In the 70s, Le Pouvoir military-FLN in Algeria carried out its Arabization policy in classical Arabic and not in Algerian Arabic. This policy resulted in a negation of the Berber identity and of the Kabyle language, tolerated at the time, pending its abolition.

[3] For Christmas or birthday presents, I often made Kabyle cassettes that I gave to American friends who listened to A Vava Inou va and Idir on Jim Haas’s show on the WORT radio station.

[4] The WORT station still exists on 89.9 FM.

[5] The ban was made by men of the militaro-FLN and its Arabist, Islamo-Baathist tendency, designated in Algeria by Le Pouvoir.

[6] There were not two languages in Algeria, but at least four language groups. There were two native, or popular, languages: Algerian Arabic, a mixture of Arabic, French, and Berber; and Tamazight (Berber), especially Kabyle. These two mother tongues, spoken in the streets and in families, were not written down. There were two written languages of the elite: classical Arabic, the language of official discourse, was very different from Algerian Arabic and was not spoken in families or in the streets; and French, the language of intellectual production, spoken and written by the majority of Algerians. Le Pouvoir, a past master in the art of manipulation, denied the existence of Tamazight as well as the diglossia between Algerian Arabic and classical Arabic, speaking only of Arabic (yes, but which one, Algerian or classical?).

[7] I was invited with a friend.

[8] The Berber language was then taught at the University of California, Los Angeles and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

[9] The word couscous is Berber and comes from seksou or kseksou in Kabyle, which gave csoucsou, then couscous.

Keywords: A Vava Inou va, Berber culture, Kabyle music, Resistance, Imazighen (Free men), Indians of North Africa.

How to Cite:

Toumi, A.B., (2024) “Idir in the Midwest of the US”, Tamazgha Studies Journal 2(1), 95-98.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 2 • Issue 1 • Spring 2024

Pages 95-98

Language: English

INSTITUTION

University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point