Homages

Remembering Idir

AUTHOR: Banning Eyre

Remembering Idir

Banning Eyre

African Music Producer

Abstract: Writer and radio producer Banning Eyre describes his rich encounter with Idir, who rose from a young poet in a Kabyle village in Algeria to become one of the most celebrated singer/composers of Amazigh (Berber) music. Idir’s life and music represent a quest of identity in post-colonial Algeria.

Keywords: Idir, Amazigh music, Berber music, Algerian music.

I am a producer for the syndicated American public radio program Afropop Worldwide. Since our launch in 1988, we have been introducing mostly American listeners to artists, sounds, and stories across the global African diaspora. My awareness of Idir began about twenty years ago, when I turned my focus to the traditional and indigenous music of North Africa. Around the time of the 9/11 attacks, the print publication Global Rhythm (since folded) published an issue focused on Arab and North African music. The issue stirred controversy because nowhere in its pages was there any mention of Berber or Amazigh music. Some took this as an unpardonable omission and a sign of how market and industry forces were—inadvertently or not—amplifying a long-standing effort to marginalize Amazigh culture, especially in Algeria. I took the controversy as a cue and began work on what became a pair or Afropop Worldwide programs called “Berber Rising 1 and 2.” And that is when I encountered the music of Idir.

The history and surviving music and culture of North Africa’s earliest known inhabitants are rich and fascinating. From the lonely folk songs of Tuareg desert nomads to the joyous sounds of Atlas mountain villages, there is depth, beauty, and vigor in these traditions. And contemporary urban artists like Houssaine Kili, Takfarinas, and Amazigh Kateb have elevated those traditions in exciting pop music. Pursuing these musical trails, I naturally came to know the great poet singers Matoub Lounes, Ait Menguellet, and Idir.

By 2007, when I finally met Idir, I was somewhat versed in Amazigh history and culture, and was excited to attend a double bill at New York’s Lincoln Center with Idir and Moroccan singer Najat Atabou, who adapts the Berber folklore of Morocco’s Atlas mountains. Before the concert, I interviewed Idir and he spoke of his beginnings in a village in Kabylia and how he came to Algiers for schooling to find himself one day in the local radio station being asked to sing a song he had composed for a young girl. He had written the song for the girl to sing, but as she was sick on the day of the broadcast, they wanted him to fill in. “But I’m not a singer,” he protested. “Yes, you are!” replied the radio producer, and so began the career of Idir the singer.

Knowing now about the history of Kabylia and the struggle to maintain Amazigh culture in an increasingly Arabized country, I understood that these issues can inspire fiery passions. But what struck me most about Idir was his serenity. If he was in any way a culture warrior, he was a gentle one, using his velvety voice and lyrical melodies as his weapons. He explained that on that day in the radio station, he adapted the stage name Idir, meaning “he lives.” He told me, “When there were epidemics in Algeria, there was no medical care, no doctors, no hospitals, and children, almost as soon as they were born, were dying. So parents were giving the name ‘Idir’ to their children in the hope that they would survive the sickness.” His choice of this name reflected a sense that every day was a gift, and on the stage that night, he emulated just this sort of beatific humility.

Idir spoke to me about the mystery of songwriting and about one song he was especially proud of, “A Vava Inou va.” He told me, “I was speaking of an ancient time, when there was no electricity, no radios, nothing like that. I was describing the members of a family at the fireplace on a winter evening—the moments when the warmth of the people was near the warmth of the fire—when our old women would tell us histories, legends, and fairytales. I was describing that, quite simply. I don’t really know what happened with those people, but if I knew the secret to songs like those, I wouldn’t do anything but make songs like that my whole life!”

Obviously, this song and others touched a deep nostalgic nerve, especially among his Amazigh fans who live with a sense that their culture and traditions are gradually being erased. The emotions such songs stirred was obvious in the reaction of the audience at Lincoln Center that night, as they rallied and swooned, singing along, and unfurling Amazigh flags.

I had asked Idir if he considered himself a political singer. He said, “Music is something one can succeed in only if one is aware of the problems of the audience, the listeners. Political singer? No. But politically engaged? Yes. I’m a child of the Algerian revolution of independence. We were leaving French colonialism and gaining our freedom when I was little. We were following Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. But soon Algeria was not letting me express myself, sing in my native tongue, and so there was something that was still giving me pain. Thus, I began to struggle for this right, and that opened the door to other issues to struggle with, like militarism and racism. So I began to get involved in these struggles with certain friends, and since then I have participated in certain political actions.”

He stressed that the cause of Amazigh people in Algeria was more a matter of identity than political power. The issue was the imposition of Arab identity in an Afro-Mediterranean setting. “I think someone who is Arab lives in Arabia, as there are people in Quebec who speak French, but they are not French. If I had never left my village I would never have learned a word in Arabic. We are, in fact, a Mediterranean country, a country with a Muslim, Christian, and Jewish history, and ties between us all because of financial relationships. The Berber cause is not really a cause, because we were never gassed or massacred; it’s not that, but a movement against integration into the cultural envelope, against repression, which are the essential elements of our predicament, and about which I sing in my songs.”

We spoke about Matoub Lounes, a singer who paid for his artistic activism with his life. “Matoub Lounes lived with me for seven months,” Idir recalled. “Our relationship was great. We shared the same ideals, and we had no reason to get angry or agitated with each other because were taking different perspectives. He was more traditional, more local, focusing on Kabylia and the region, and I was more modern. I guess I was getting at something larger with my music. But I really admired his artistic fiber. He was a charming guy. He had a good humor about him that you just couldn’t turn off. He reminds me in a way of the French poet Arthur Rimbaud, in the way he expressed his sadness. I had a lot of affection for him.”

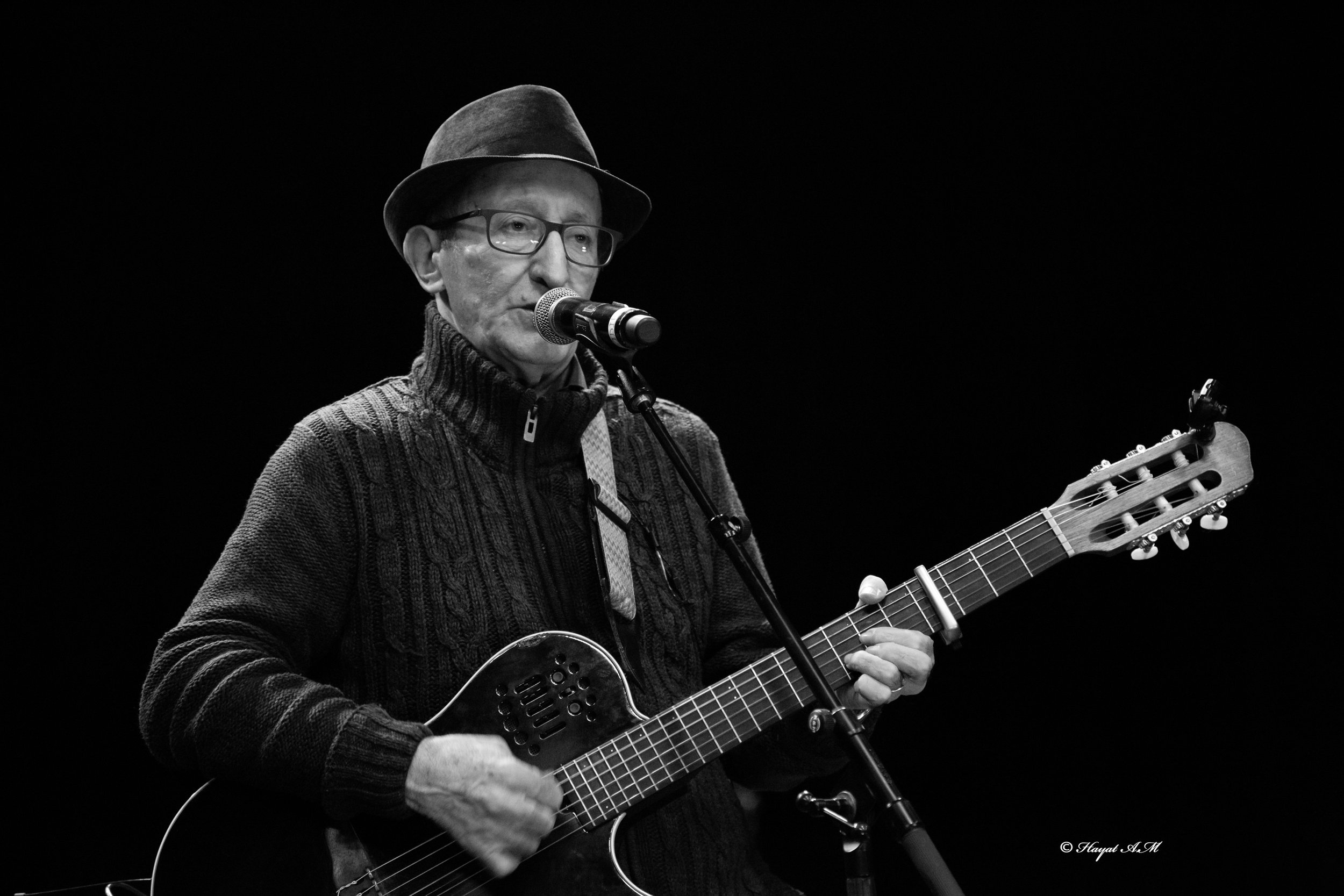

FIG. 1. Idir. Credit: Hayat Aït Menguellet

Idir continued, “In our culture, poets have more power than politicians. That stems from the fact that our culture is one of oral tradition. Two hundred years ago, you would find that when two tribes went to war, each side had its poet, and the poets fought with words. The one who could throw out the most beautiful word won, and the war would end, because the word is above economics, politics, business, etc. Poets have a position of choice in our society. We had a poet named Si Mohand in the nineteenth century, and in 2008 all his poetry is still known [in Algeria], even when people lacked a written language. It was all transmitted by the oral thread, from mouth to ear. That’s fabulous.”

I mentioned to Idir that I had never been to Algeria, that my main exposure to Amazigh culture was with the nomadic Tuareg in northern Mali. He brightened at the mention, noting that Tuareg music had inspired him. “Their language has evolved somewhat differently than ours,” he noted, “but it’s a matter of accents. It’s less a difference than in the Celtic world, where a Scots speaker may not necessarily be able to communicate with an Irish speaker or Welsh speaker. But all of us Berbers—the Shleuh and Rifis of Morocco, the Kabyle, the Tuaregs—at the end of fifteen days at most, one can grasp the differences and speak one with the other.”

This in turn inspired me—to think that this vast, varied and ancient set of peoples we call Berbers, whose history reaches back far beyond human record, still share such a connection despite all the struggles and conquests they have endured and the austere geography that divides them. But as I watched Idir sing that night, I also felt that the simple beauty of his songs, his voice, his calming presence, was enough all on its own. Even had I known nothing of the history and activism his work reflects, I would have been equally moved by the man and his timeless music.

Keywords: Idir, Amazigh music, Berber music, Algerian music.

How to Cite:

Eyre, B., (2024) “Remembering Idir”, Tamazgha Studies Journal 2(1), 90-92.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 2 • Issue 1 • Spring 2024

Pages 90-92

Language: English

INSTITUTION

African Music Producer