Homages

Idir Beyond Kabylia

AUTHOR: Joseph O. Krause

Idir Beyond Kabylia

Joseph Ohmann Krause

Oregon State University

Abstract: This short statement pays homage to Idir in two ways. First, that he was an artist celebrated internationally, particularly thanks to his album, Identités. Second, that his songs not only convey the soul of the Amazigh but are attached to a larger African cultural movement, namely to négritude.

Keywords: Idir, Karen Matheson, Maxime Le Forestier, Tizi Ouzou, Kabylia, At Yenni, Senghor, Rabémananjara, Césaire.

I.

Who, for those with no knowledge of the Berber language, can forget somehow understanding it spontaneously, musically, without total misinterpretation when Idir and Karen Matheson sang the opening track, A Vava Inou va, on the 1999 album Identités? The sound was clear: pure music, higher rivers in the lyrics, a gift of language ascending far back in time and downflowing again to us, barely newly literates. On that same album came Tizi Ouzou, sung with Maxime Le Forestier and Brahim Iziri. With that combination of voices, Idir made a long but lyrically smooth connection between the Berkeley anti-war movements of 1968—by re-phrasing Le Forestier’s original song San Francisco—with the 1980 Kabyle Spring uprising seismically centered in the cities of Tizi Ouzou and Bejaia.

Le Forestier:

It’s a blue house

Nestled against the hillside…

Idir:

Tizi Ouzou is awakening

Going after its dreams…

As the young Hamid Cheriet, Idir must have sung attentively in different languages at his mother’s skirts. And close to dark after school, must have climbed the hills where Arabic and French were hardly heard even on the downwind. Old words still full of life, bits of music to be remembered and rejoined. And, when he was older, after the army and first odd jobs, casting a new gaze on the high ridges. Recording songs now up in the mountains on a small tape player. Perhaps he had heard of Béla Bartók, who had crossed the Balkans in search of the same musical remembrance.[1] The mothers of the Rom sang to their children in the same way that hair was caressed and combed across Kabylia.

A remembrance up and across grazing paths, the late spring transhumance. Footsteps and hoofs back and forth through the centuries, something one hears in Idir’s voice, as if just before the rain. From centuries back rather than from exile. The voice in his song Tayemmatt (Birth of the World) from his 2013 album allows us to hear that ancient history without its shackles.

Most of all, he went far beyond Kabylia and Algeria into a larger world that only music and song can enter.

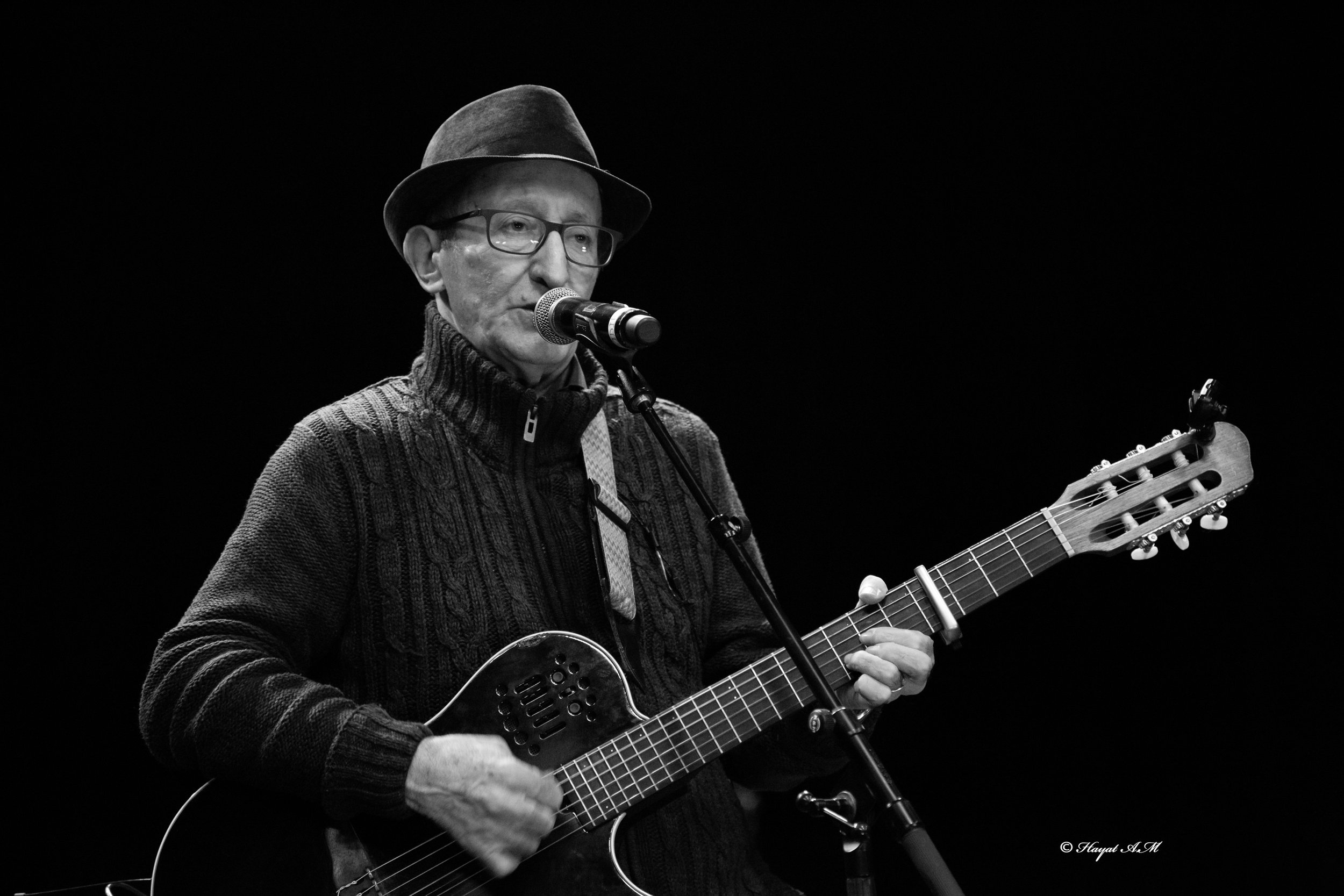

FIG. 1. Idir. Credit: Hayat Aït Menguellet

II.

When he was a young man, there must have been several reckonings in Idir’s thinking. Or recognitions, as he went from his mountain village (At Yenni), with the songs of older women still at the back of his own voice, downward to the plain, to his early collaboration with Mohamed Benhamadouche. And then new reckonings as he eventually crossed the Mediterranean until, after years, a forged voice became known internationally. One that found a way to transcend the hard corners of Algerian independence, the lonely memories of the 1980 Berber Spring, and the ongoing trauma of that dark decade. In his own lyrical incantations, Idir allowed a village fountain to spring forth to a wide audience. He followed the same riverways descended by Léopold Sédar Senghor in Senegal and Jacques Rabémanajara in Madagascar.

Yet, like Senghor, is Idir or not above all l’Africain? Singing out from the sand a musical language of long cultural roots recently pushed down by denigration? While attending the First Pan-African Cultural Festival held in 1969 in Algiers, what did he hear and see that insisted he go beyond Kabylia? Beyond the flapping of flags and the gardening of borders? In a way, the Tamazight language, as subversive as it may have originally been in the 1980s, was a solution. It afforded an artistic path out of both the political and religious premises of Arabization and the French colonial connections. If Senghor, Césaire, and so many others wrestled with the postcolonial fluidity of French, Idir in a sense worked backwards, upstream. Tamazight could be the vehicle in the long exchange for a larger artistic purpose.

When Idir’s hit song A Vava Inou va was first heard on the radio in 1975, it must have been celebrated in every village in Kabylia.[2] It was also heard in France and on airways across the world. It is a song, like the tale of Little Red Riding Hood, about danger lurking at our door. A song about our fears, longings, and hopes. It was a song that would bring Idir far beyond Kabylia because in its fluency it expressed an ongoing human story.

Idir just left us. Quietly, though amidst the falling sounds of autumn. Some, Lounès Aït Menguellet in particular, have long been by his side, walking the same path—searching the guitar frets for the right chord. Idir left quietly, opening the door wide for others to step outside, however faintly they hear his voice.

Footnotes:

[1] See Christopher Orr, “Songs of Discontent: The Kabyle Voice in Post-Colonial Algeria.” MA Thesis, The Pennsylvania State University, 2013. https://etda.libraries.psu.edu/files/final_submissions/8441

[2] Jane E. Goodman describes the early impact of Idir’s songs in her article, “Idir: How a Song from the Village Took Algerian Music to the World,” https://theconversation.com/idir-how-a-song-from-the-village-took-algerian-music-to-the-world-141418

Keywords: Idir, Karen Matheson, Maxime Le Forestier, Tizi Ouzou, Kabylia, At Yenni, Senghor, Rabémananjara, Césaire.

How to Cite:

Krause, J.O., (2024) “Idir Beyond Kabylia”, Tamazgha Studies Journal 2(1), 83-85.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 2 • Issue 1 • Spring 2024

Pages 83-85

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Oregon State University