Essays

The Sound of Tenderness in a Hard Time

AUTHOR: Diana Wylie

Sounds of Tenderness in Uneasy Times

Diana Wylie

Professor of History Emerita

Boston University

Abstract: This essay tells how Idir’s music was heard in 1976 by an American teaching in Oran. His sounds counteracted the tension in the streets of a city still recovering from the war, now subjected to the militant rhetoric of the FLN. Idir sang tenderly and in Kabyle. His music and lyrics expressed peaceful, almost feminine, post-revolutionary visions of nation and manhood.

Keywords: Manhood, memory, Oran, A Vava Inou va, Algerian society.

1976 was a year of shouts and murmurs. That soundscape—shouted cries, murmured news —dominates my memories as I cast my mind back now, forty-five years later, to the time I taught at the University of Oran. Shouting boys filled the streets, playing and fighting over games of football. An adult version of their loud cries could be heard in the proud nationalist rhetoric of the day. Murmurs are, of course, harder to hear. At the time, they often took the form of whispered complaints about military officers unfairly rewarding themselves with abandoned French property. The war was over, but sounds of disquiet—loud and soft, hard to interpret—were in the air.

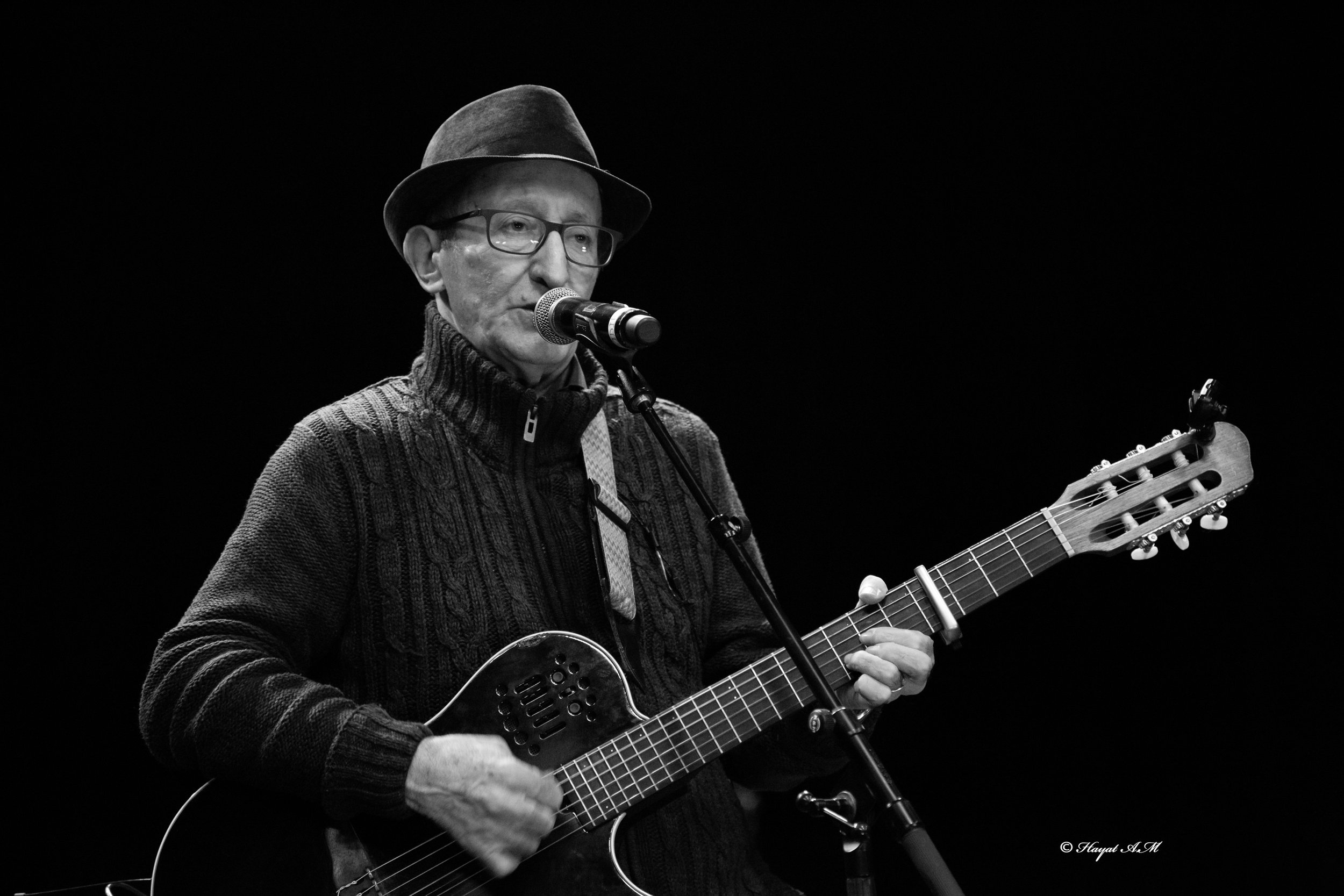

Less explicitly political murmurs could be heard, too, if one were patient or lucky. Fortunately, a music cassette came my way that year, introducing me to the mellow voice of one young singer accompanying himself on the guitar. The all-too-rare tenderness of his tone had the extraordinary power to unclench the defensive or combative stance of listeners like myself who were living in a place still fraught with conflict.

Idir was singing as a new, post-revolutionary man. Neither his sound nor his lyrics celebrated martial values. He was no musical moujahid. Neither was he an ‘Omar Gatlato.’ While his first album debuted the same year as Merzak Allouache’s popular film, he bore no resemblance to the title character, a man bored by tales of heroism and immobilized by self-doubt. Idir turned his back on both kinds of manliness—bombastic and bewildered—and gave his listeners a different sound: tender, reflective, and unabashedly grounded in his own roots in the Kabylie Mountains. Idir’s first song on the album is a lullaby; and the first voice heard in that song belongs to a woman. These two facts alone send a liberatory message, if liberation is understood to be more complex than the claims made by armies and slogans. By appreciating the strength in the feminine and frankly acknowledging weakness, he seems to be inviting men to liberate themselves from the narrow roles of combat and defense.

The lyrics sung by Idir express tenderness toward those who are vulnerable, whether they are infants, old women, children in wartime, men plowing dry fields, or simply people who doubt. The famous opening lullaby, for example, celebrates the sound of the mother’s voice over the centuries: her song stops time and exorcizes fear; it creates warmth, like that shared by men sitting around a fire; her rhythm is both immemorial and modern, a mixture of today’s tools and ancient enchantment. In this sense, A Vava Inou va seems intended to be not just a lullaby. Rather than simply aiming to put the baby to sleep, the song uses ancient sounds and invokes ties of solidarity to keep fear at bay. Following the few bright opening notes plucked slowly by Idir on his guitar, the song celebrates the capacity of inherited culture to sustain us in modern times, when all of us are in some way vulnerable.

Idir celebrates but does not idealize rural life. Sometimes his rhythms imitate it to comical effect, as in a roundly churning song about beating milk to make petit-lait (Ssendu/voie lactée), the trudging beat that mimics a peasant behind his wheelbarrow (Izumal/derrière les barreaux), or the pitching from side to side of a laden donkey climbing a mountain track (Isefra/voyage). He deploys dark comedy in a song (Azger/Le Boeuf) about a cow contemplating human ingratitude for all its gifts of sweat, flesh, and skin.

Idir’s vision is decidedly humanist. In this first album, he mentions the nation not once and God only twice, albeit in a utilitarian way, when he acknowledges that suffering people tend to turn to Him for solace. Spiritual salvation may be found in communion with others. The city, though, offers no occasion for celebration; its neon lights and money have torn apart families. Migrant fathers never see their children grow, so they turn to God, beer, and other drugs to fill the void. Recovery from this terrible estrangement could begin with a fistful of earth (“cette bonne vieille poignée de terre”), Idir suggests, using a metaphor for heritage that could be lost on no one. Immediately thereafter, he launches into a party song viscerally communicating a communal celebration—Sing! Dance! Eat! (Zwit/Rwit). His strong syncopation mimics exuberant bodies moving their shoulders and feet in unison.

Idir’s music was taking me beyond the shouts and murmurs of Oran’s streets. He was revealing aspects of Algerian society that were not easy to perceive in a city that had flipped from majority European to almost entirely Algerian by the time the war ended, only 13 years before I arrived. That I was ignorant of the Kabylie at the time—I had visited only once and had just one student from there—proved to be no barrier to my appreciation of his music. I did not know that 1975 had been a year when emigration to France by Kabyles, Idir among them, was rising. My attention was drawn, rather, to the Charte Nationale, where I carefully underlined in red the sentences setting out the country’s socialist objectives. Reading the Charte’s yellowed pages today, I see I left unmarked the opening “Characteristics of the Algerian Nation” that ignores the Kabylie and refers instead to Algeria as an “integral part of the Arab world” by virtue of shared “language, religion, and culture.” I now readily notice that the Charte failed to invoke Amazigh language and culture as having a role to play in achieving the three objectives of socialist Algeria: to “consolidate national independence, found a society freed from exploitation, and promote the free blossoming of human potential.”

The rhetoric that did penetrate my consciousness in 1976 came partly from my students. Their pride in the revolution led them to assemble posters labeled with slogans like “Jeunesse mondiale Progressiste, Unie contre l’Impérialisme et ses valets.” They sat smiling before this backdrop so I could photograph them. One left-wing militant easily whipped up student petitions against perceived slights to the Algerian revolution, but for the most part the students were intent on becoming upwardly mobile. As university students of English, they would surely find jobs allowing them to buy a house and car. Only a few bothered to observe that, since our eggs had to be imported from Spain, the five-year-old Agrarian Revolution must not have been doing well. None of them told me they feared that the young country’s fiscal well-being would be in danger if oil prices declined and if the interest rates rose on its many foreign loans, as eventually proved to be the case. With either a prescience or frankness that set him apart from my more optimistic students, Idir’s lyrics gently draw attention to social suffering, which at the time took the form of emigration, rural poverty, and being subject to unresponsive “gens du pouvoir.”

As historian James McDougall has recently observed, the 1970s were marked in Algeria by a rising cultural revolution against the “degradation of morals.” The Ministry of Religious Affairs called for “social remoralization” against the threat posed by “internal enemies, corrupted by foreign influences.” Idir’s songs do not convey a tone of fierce moral judgment against “dissipated masculinity, threatened femininity, and a generalized moral disorder.” In effect, he was rejecting both the reassertion of patriarchy demanded by the Ministry of Religious Affairs and, by virtue of his departure for France, the xenophobia being peddled by El Moujahid. (That some disgruntled people bought this line was evident when a mild-mannered British colleague had his passport thrown back at him by a bank clerk who called it “trash.”)

While I saw no signs of “generalized moral disorder,” I was struck by a sense of pervasive unease. Oran had the air of a city where people did not yet feel at home. I rarely heard laughter. The young boys playing soccer with improvised balls seemed to be fighting with each other most of the time, though often they were bawling because they had been walloped by an older man. The pent-up energy of these street-boys burst into public display when Morocco appropriated Spanish Sahara. The boys ran through the square in front of the post office, knocking over tables in their delight at being able to command the street without reprimand. Perhaps some of them came from the formerly Spanish neighborhood of La Calera, so full of recent and very poor rural migrants that its buildings seemed about to tumble down the steep escarpment into the sea. The whole city of Oran, not yet possessing a sense of community, felt precarious.

The musical soundscape, as I experienced it, reflected this precarity. It seemed to be strung up between two poles. On the one hand, there was loud rock music played by a shaggy band of electric guitarists wearing bell-bottoms. On the other was a concert of dreamy, Andalusian-derived music strummed on oudhs by dignified older men wearing jellabas. These styles, as I remember them on two particular evenings, exemplify a dilemma Idir must have encountered—whether to emulate rock or to faithfully reproduce inherited sounds. Instead, he chose a third way that bridged past and present, rural and urban. “I came at the right time and with the right songs,” he told Agence France Presse in 2013. The times were ripe for Idir’s music and lyrics in the sense that he rejected both the shout of western rock and the murmur of the oudh in favor of a genuinely Algerian sound that was not conventionally patriotic and proved to be beguiling internationally.

Since I did not understand the Amazigh lyrics when I heard Idir’s songs in 1976, I had to rely on the music to convey their meaning. What I sensed is the following, now confirmed by the lyrics themselves: bittersweet memories; a gentle regard (for children, the old, women, and mothers); a desire to protect rather than subjugate; a longing for beauty (especially natural) and for justice (that hard work will be rewarded). Idir’s music unambiguously expresses all these feelings. Openness to the feminine and a contemplative tone set A Vava Inou va apart both from songs at the top of the American charts in 1976 and from the rai then starting to rise to international prominence. Idir’s murmuring voice had extraordinary power to drown out the shouting and to express a new post-revolutionary manhood in uneasy times.

Keywords: Manhood, memory, Oran, A Vava Inou va, Algerian society.

How to Cite:

Wylie, D., (2024) “The Sound of Tenderness in a Hard Time”, Tamazgha Studies Journal 2(1), 80-82.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 2 • Issue 1 • Spring 2024

Pages 80-82

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Boston University