Essays

A Folk Artist and His Folk

AUTHOR: Ignacio Villalón

A Folk Artist and His Folk

Ignacio Villalón

Council of American Overseas Research Centers (CAORC)

Abstract: This paper focuses on how Idir’s music went far beyond the local in its inspiration. It tries to understand Idir by situating him in the larger landscape of both the histories of music and of Algeria. This paper shows how the Czech (Bedrich Smetana) and Kabyle (Idir) musicians so geographically and historically distanced shared sensibilities based on esthetic tropes of peoplehood and natural word. Both Smetana and Idir told the world of their respective peoples in a musical language it could understand. From this point of view, Idir’s music can be considered as a mean to guarantee a Berber Volk a place in the world even though it was stigmatized locally as a provincial identity. For Idir, the world was composed not of countries, but of villages, an international composed of the local.

Keywords: Volk, Peoplehood, Czech composer Bedrich Smetana, kabylité, Amazighisme.

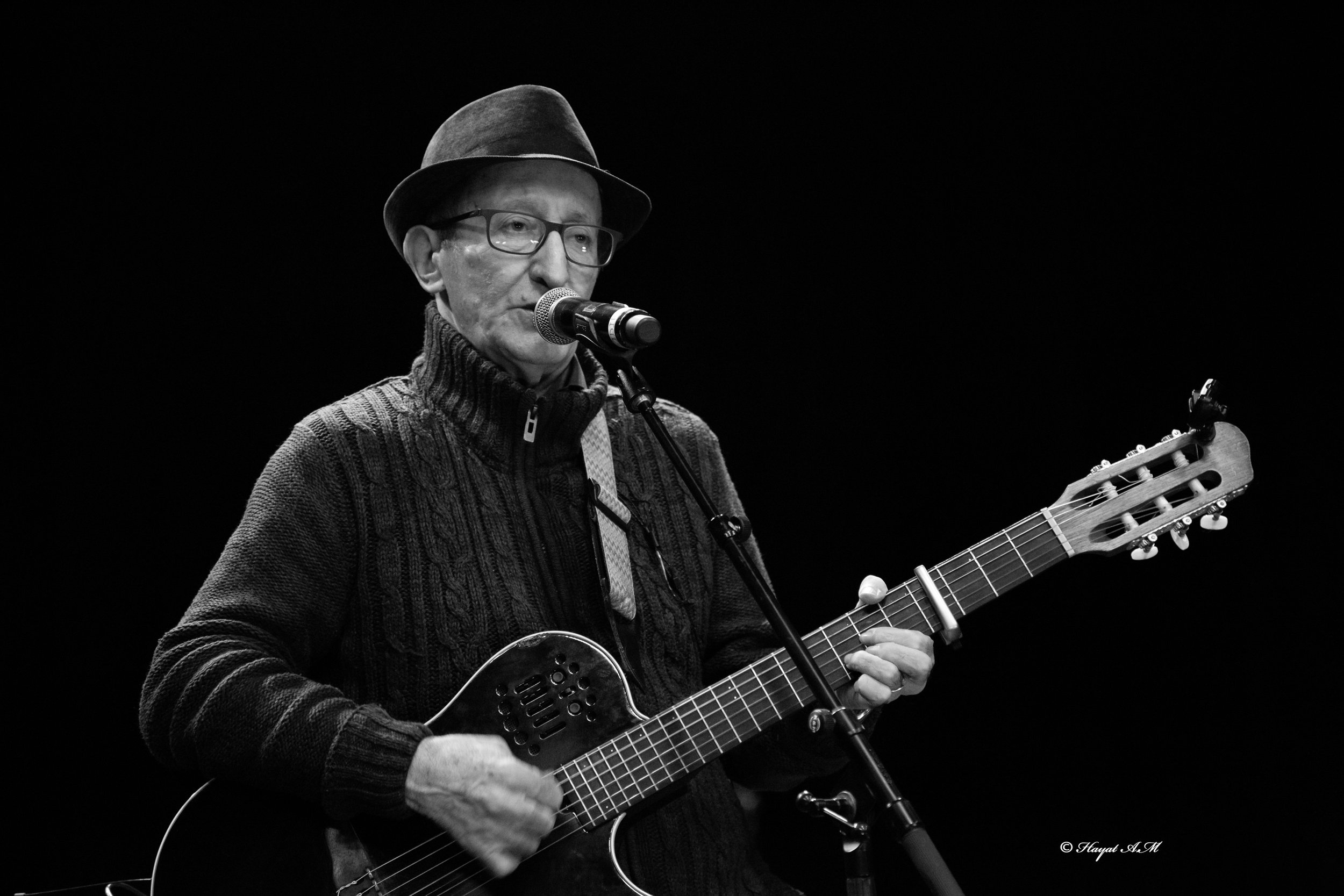

Since Hamid Cheriet passed away a couple of years ago now, his legacy has been in the hands of the living. But even during his lifetime, forces that far preceded and surpassed him helped secure his place in the pantheon of North African music. At the beginning of his career, his stage name, Idir, served as a veil of anonymity, but after he appeared on television and on the cover of his debut album, A Vava Inou va, in 1976, he found it erected as a symbol of Kabylia. Idir was the name that Hamid used to carry the lofty aspirations he inspired in his audience, a word that helped to designate his responsibility towards them.

While celebrity musicians across the board find themselves navigating their public personas and the expectations of their fans, Idir belonged to a more limited subset of artists: those whose audiences coincide with larger sociopolitical aspirations, audiences imagined to constitute a people. Idir’s musical choices as well as his interactions with his audience reflected a commitment to the shared project of valorizing Kabyle culture. But at the time of his emergence, the populations of northeastern Algeria had only begun to be seen through the prism of peoplehood. Historically, Kabylia, which was understood to comprise a region for linguistic, geographic, and religious reasons, had nevertheless been seldom thought of as a single coherent political unit. After all, the idea that shared language, geography, and religion ought to constitute a polis was born outside of Kabylia. Idir’s music, for all its kabylité, also went far beyond the local in its inspiration, successfully mobilizing musical expressions of peoplehood originating far outside Algeria. It strikes me, then, that Idir’s specific contribution to the role of “people’s musician” can be better understood by situating him in the larger landscape of both the histories of music and of Algeria. From this vantage point, it is clear that Idir navigated, both consciously and subconsciously, through an international forest of peoplehoods, for which I will try here to sketch out something of a map.

The Volk in Music

When Idir entered the world, the idea of the “folk” had already witnessed countless births around the world in different iterations. During the 19th century, with the rise of nationalism in Europe, the newly theorized concepts of people, peuple, and Volk found their way into the classical music of the era. Czech composer Bedrich Smetana’s “My Fatherland” neatly expresses some of the esthetic tropes of peoplehood in classical music: in the famous second movement, named for the Moldau river, Czech folk melodies are interspersed within a larger, swelling symphonic poem. Similarly, the natural world, in the form of soaring avian flutes and in lyrics that are mixed in with folk stories and melodies, figures prominently in Idir’s music. In Adrar Inu, for instance, the narrator tells of his love for the mountain where he seeks refuge; and in Ageggig, he sings the story of an anthropomorphic flower that is cut down and becomes a star. The message expressed in Smetana’s and Idir’s musical choices goes something like this: just as birds chirp and dart above the water and along the mountains, so too are the Czech or the Kabyle tied to this land, speaking their language and living with its nature. That two such geographically and historically distanced musicians share these traits is not necessarily surprising. A people is only a people if it is recognized as such by those who do not belong to it, and hence, it must be expressed in an established common idiom. Both Smetana and Idir told the world of their peoples in a musical language it could understand. It can be said that Idir’s music sought to guarantee a Berber Volk a place in the world, when in Algeria, it was being relegated to a provincial identity.

But Idir’s marriage of peoplehood and music was also a different one, hipper to the beat of his time: that of the folk musician, guitar in hand, singing popular music for the people. The American troubadours of the mid-20th century had contributed to the development of the persona’s most prominent tropes. If Woodie Guthrie mostly wrote his own songs, while Pete Seeger mostly sang those of others, they told a similar story about the folk music genre: it was authentic because it was about the past, present, and future of the common people of America, as recounted by a native son. In the United States, the genre’s conflict between its backwards-looking inspiration and its forward-looking politics evolved in the 1960s as a generation made an overt break with the past. Where the European nationalism of the 19th century had dovetailed with state-building projects, the American folk artists of the 20th century represented a countercultural vision of peoplehood that was pitted against the government, but for the people. Whatever the more specific evolving meaning of folk artistry might have been in the United States, by this time, a generic template of the folk artist had some international appeal in a world of newly-independent nations and new state-building projects. What did the persona of the folk artist do for Idir specifically? It was a broad template, which allowed him to sing in Kabyle while being international, to play the guitar while being traditional. And unlike the classical idiom in which Smetana expressed himself, it also telegraphed an image of the everyman. In this way, it strikes me that while Smetana quoted folk melodies, Idir could purport to speak them.

Meanwhile, the Folk in Algeria

At the moment Idir emerged on the stage, peoplehood was a chief ideological and rhetorical concept being mobilized by the architects of the new Algerian state (who drove the point home by calling the country both démocratique and populaire). But in Algeria it is far more than just a cynical tool of governance, for the idea of the people, cha’ab, was forged in a shared colonial experience and has particular resonance among its citizens. Nationalist culture has often stood in opposition to the state, as with the current hirak movement—to which Idir lent his support—that has made use of such slogans as fakhamat ech-cha’ab (“Their Excellency, The People”) and reused the classic Un seul héros, le peuple, emblazoned on many casbah wall and immortalized in photographs. Peoplehood figures in Algerian musical history, too. The cha’abi genre, established in the 1940s and 1950s as anticolonial sentiment came to a boil, was founded by Algérois musicians singing of morality in a dialectal Arabic consciously devoid of French loanwords.

But whatever political and cultural resonance the idea of an Algerian Volk may find in 20th and 21st century Algerian history, when Idir was singing, a different—if at times overlapping—people came to mind. President Houari Boumediene’s overtly Arabist cultural policies created an image of Algeria foreign to many of its citizens, giving way to a desire for cultural affirmation—as evidenced by the Berber Spring of 1980—that fueled Idir’s rise to stardom. In this context, Idir was a specific kind of artist. There had been Kabyle musicians before, but none, with the possible exception of Djamel Allam, had been so overtly tasked with representing Kabylia itself. Was Idir singing the song of his forefathers? Perhaps. But despite the nostalgia that his musical choices could connote to his audience, he was first and foremost a musician of his time. Within Algeria itself, Idir was able to birth musically a vision of Kabyle peoplehood intimately wrapped up in the present, which could be mobilized not so much against the notion of Algerian national peoplehood in general, but rather to this form of Algerian peoplehood.

The World According to Idir

The international system, goes the theory, is composed of nations headed by autonomous, sovereign governments. In Algeria in particular, where both state and citizenry emphasize national sovereignty as a driving value of politics, this vision of the international system is especially strong. Never close to statecraft but never too far from politics, Idir, through his affirmation of kabylité, proposed a different vision of the international system. According to Idir, the world was composed not of countries but of villages, an international comprised of the local. Certain juxtapositions make this clear: his bucolic lyrics written for an international audience; his instrumentation, part local instruments like the flute and bendir, part guitar and piano; his back-up musicians, almost always Kabyle or non-Algerian. In our era, this organization of the world has an air of the intuitive to it, for it marries a universalist ethos of the brotherhood of humanity to a sense of identity theoretically forged in the most concrete aspects of daily life: at home, in the town square, at the market. It brings the most abstract together with the least abstract and does away with the intermediate.

In between these two, however, is a forest of folks, presumptive peoples whose claim to existence lies somewhere between the local and the international. Idir engaged with these ideas cautiously but consciously, collaborating, for example, with Cheb Khaled in a show of pan-Algerian solidarity during the fractious 1990s. He also engaged, of course, with another in-between ideology of peoplehood, that of Berberism, to which he owed much of his success. Amazighisme is a standard carried by those claiming to be Amazigh; but those who claim to be Amazigh are often very different from one another. When Idir performed in Algeria, fans from neighboring Tunisia and Libya—countries that, like Algeria, had sought to imitate the pan-Arabist model in their cultural and linguistic policies—brandishing the letter yaz on shirts and banners would at times cross their national borders to see him. When Idir performed in Mali and Niger, he would often do so with Tuareg musicians in a show of pan-Berber solidarity. Even the narrower identity of kabylité is decidedly neither local nor international. When Idir performed in Paris, where he lived as an adult, the Kabyle diaspora would appear in great numbers. This group consisted of many Kabyle speakers born in Kabylia but living in France, like Idir himself; it also consisted of second- and third-generation people of Kabyle origin born in an alienating post-colonial France yet solely francophone, for whom Idir’s music represented a mythical link with their racines. What do all these people have in common? Who are Idir’s people?

A Song for the People

It is not entirely fair to ask of a communitarian sentiment so intertwined with a nationalist vision of peoplehood that it be consistent, when all signs indicate that nationalism, generally speaking, is an inconsistent worldview. The better question is: why was it that so many people saw a shared symbol in Idir?

At the time of his emergence, a vague but important shift had occurred in the arts at the international level, coinciding with the steady entrenchment of the international system. When musicians from Kabylia played music prior to the emergence of Idir and Djamel Allam, it was discernable—by the rhythms and melodies, as well as the instrumentation and lyrics which circulated in the region through the people who lived there—that they were from Kabylia. But at the time Idir emerged, simply playing as if one were from a certain place was no longer enough to ensure that the specific esthetic choices in question—those indicating a sense of regional belonging—would be carried through to later generations. As the tides of modernization spilled out of Europe into the policies of newly independent nation-states, the ways in which people from certain places did certain things had to be reconsidered in new terms: those of culture. A cluster of dates suggests something of the political origin of “culture”: in 1969, the Pan-African Cultural Festival took place in Algiers; in 1972, 193 countries and territories signed the UNESCO convention that effectively birthed the World Heritage Site; and in 1976, away from the corridors of power but still in the world of politics, Idir transcended the status of a musician from Kabylia to become a player of “Kabyle music.”

This change from playing the music associated with a place to playing the music of one’s people was strongly felt by those who, up until then, had feared that they, in this world of peoples with their cultures and states, had perhaps no place at all. “I know neither where I come from, nor where I am going,” sings Idir’s narrator at the beginning of Muqlegh, before his convictions harden: “I am returning to Berber country/Jugurtha, I have caught a glimpse of your face…If we deny our identity/we will never recover it again.” Idir’s most important legacy is that he carved out a place for those whom nations and nationalisms threatened to overrun and quell by using some of the very tools that these nationalisms had made commonplace. The modern world system demanded a politics based on the theory of the self-determination of peoples, and so Idir, humbly, through his music, laid claim to his kabylité. As a result, he lived a life with that glorious and truly international vocation that his time and place allowed him: to serve the people.

Keywords: Volk, Peoplehood, Czech composer Bedrich Smetana, kabylité, Amazighisme.

How to Cite:

Villalón, I., (2024) “‘A Folk Artist and His Folk”, Tamazgha Studies Journal 2(1), 73-76.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 2 • Issue 1 • Spring 2024

Pages 73-76

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Council of American Overseas Research Centers (CAORC)