Essays

Idir and Mammeri: From the Particular to the Universal

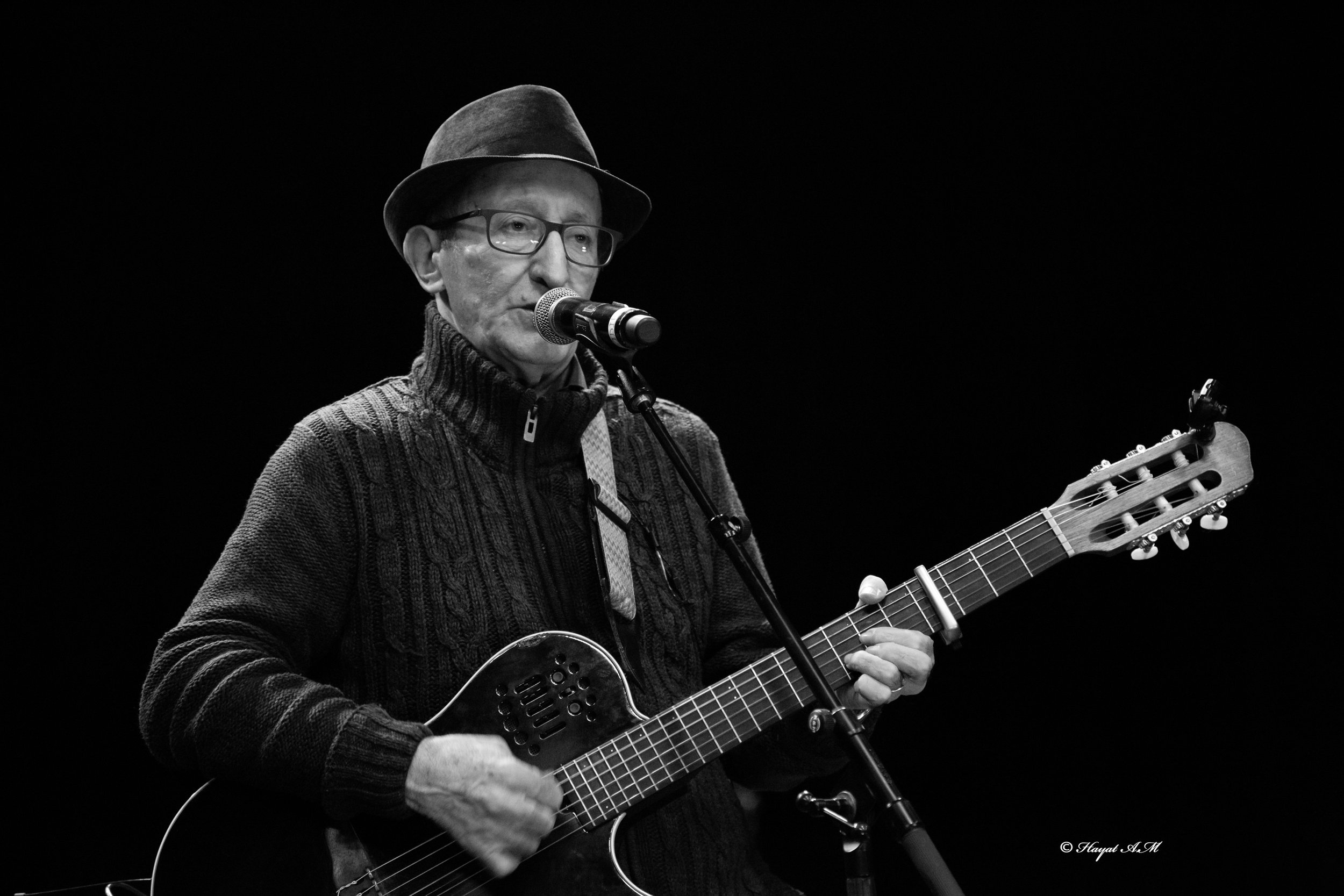

AUTHOR: Djamel At Ikken/Djamel Amrani

Idir et Mammeri: From the particular to the Universal: Two Cultural Ambassadors Cross Paths

Djamel at Ikken/Djamel Amrani

Montreal

“You know, Hamid (Idir), I did not think I would live to see the light of our culture so magnificently reignited and so beautifully rendered. You have restored it to its rightful place, and up in heaven I feel that our ancestors are cascading blessings down on you in the form of stardust.”

– M. Mammeri

Taourirt Mimoun, where the Kabyle writer, ethnologist, and intellectual Mouloud Mammeri was born over a century ago (in 1917), is but a stone’s throw from the village of Ath Lahcene where the singer and geological engineer Idir was born in 1949. The villages stand on two neighboring hills in a region known for its gold jewelry-making and armory, where entire generations of jewelry artisans are famed for their skill, but whose landscape also bore witness to verbal sparring matches and the passage of an ancestral oral tradition from generation to generation. Their art could be found both in great city centers (Algiers in particular) but also in mainland France and with the Kabyle diaspora across the globe.

Idir and Mammeri, at different pivotal moments in the history of the region and the entire country, lived through a Kabyle exodus to larger cities and the uprooting of tranquil life of the Kabyle hills. One was conscripted at an early age in the African contingent of the Allied Forces and fought in the Italian campaign and on the European front against the spread of Nazism. The other, decades later, fought in the service national, mandatory military service for every young man his age. The shock, or discovery of the Other, that both underwent would leave a lasting mark on the lives and journeys of both Mammeri and Idir, since both were rocked by conflict that they did not ask for, and both were forced at a young age to confront the devaluation of their native culture in the condescending gazes of colonizers and forgetful “city-dwellers,” either ignorant of their own culture or conditioned by an illegitimate power that negates all that does not comport with its vaguely Jacobin, monolingual worldview, forcibly tied to an all-powerful and negative Arab-Islamic ideology.

For one of these men, being Kabyle and indigenous created a double negation, in being both colonized and belonging to a cultural minority that has often been relegated to the margins of history in comparison to a “high culture” that derives its legitimacy from an age-old written tradition. The other, when barely more than an adolescent, was made to endure the sarcasm of his high school classmates, as they mocked his thick “mountain accent” and imposed their disdainful, folklorizing view of his language. Such attitudes might have pushed one or both of them to give up or to revolt. But no!

Both, paradoxically, chose a path of openness and creative intelligence. Very early on, both saw the necessity of mooring themselves to a heritage anchored in their lived experiences. They discovered poetry, stories, cosmogony, myths and legends and Tamusni, all of which naturally nourished the Kabyle social body with a language that was self-evident because it was native to both of them.

These ties would mold a resistance/persistence in the face of rejection by colonial academia which studied Kabyle culture (and Berber culture, in Mammeri’s case) only marginally or through a Eurocentric lens at best. Mammeri chose the tool he knew best, literature, to express his individuality to a monolithic world. La colline oubliée (The Forgotten Hill), his first novel, was not only a literary fiction but a fresco depicting a world and culture that was alive despite the drama and vagaries of an often tragic history and a fundamentally ungrateful land.

In another way, but no less importantly, Idir (Cheriet Hamid) was shaped by the schools and universities that denied the existence of his language in favor of Arabic or French, as were countless young people of his generation born in Kabylia and living in the melting pot (though majority Kabyle) city of Algiers. Instinctively, Idir charted a course in the arts, and sought–without a clear plan– a unique way of captivating the many listeners who had been shaped by the catalog of Eastern music, or others who had been carried away by the first decibel-thumping “boy bands” of the West.

Two factors would play a profound role in shaping Idir’s path forward. First was the artistic microcosm of Radio Kabyle, whose offices were just across from the high school that Idir attended. Renowned artists like the virtuosic Cherif Khedam, poets, and radio producers like Ben Mohamed, Mohamed Belhanafi, Meziane Rachid, Hocine Ouarab, and Ali Necib all passed through those doors and gave off an aura that the young Idir, already obsessed with music and poetry, could not help but be moved by. Meanwhile his elder, Mouloud Mammeri, had already paved the way for the emancipation of his language and culture through a precocious literary aptitude that made him one of the founding voices of Francophone literature in North Africa, and by way of seminal research in Berber studies that gained considerable momentum and a supranational aura in his powerful work.

The Poems of Si Moh ou Mhand, originally published by the novelist Mouloud Féraoun, were enriched, revisited, and recontextualized by Mouloud Mammeri, who added an erudite preface that highlighted the origins and depth of the poems and praised the impact of “Mohandien” language, along with the poets who were Mhand’s contemporaries, on his society.

During recreational trips organized by the Ben Aknoun circle of academics, which included “veterans” of Kabyle music like Cherif Kheddam, up-and-coming talent not unlike Nouara, and occasionally young researchers from CRAPE, the Center for Anthropological Research, (or else the Center’s director at the time, one Mouloud Mammeri!) Idir found fertile ground for meetings, exchanges, and a common intellectual launchpad in the search for innovative ways to express himself through what he knew best (music) and what he loved best (poetry)!

It wasn’t by chance that Idir and artists like Mennad, Ben Mohamed, and Ferhat found themselves sitting at Mammeri’s feet when, in the 1960s, he took advantage of a gap in his ethnology course load to offer a semi-informal Berber class, which soon attracted dozens of high schoolers and young university students. There, they discovered new possibilities and channels of expression and emancipation for the Berber-Amazigh culture, in order to escape the feeling of “internal exile” in a country that denied all differences, and worse, demonized and waged war against them using every apparatus of state ideological control (schools, the media, political control, policing). Another coincidence, or convergence, came in 1973, by chance the same year that the University of Algiers eliminated Mammeri’s Chair of Berber Studies. Idir scored a hit with the song “A Vava Inou va,” from a poem by Benmohamed (Mohamed Benhamadouche), a fine poet and pioneer of the textual and formal modernization of Kabyle poetry. Somewhat prophetically, Mammeri was asked to write the liner notes for this 33RPM record, which marked a new wave in modern Kabyle/Algerian protest songs. At the time, the great poet and writer Kateb Yacine, author of the celebrated novel Nedjma, called them Maquisard songs, or Resistance songs.

In the Beginning was the Tale… and a “Prophetic” Preface

The major overnight success of this type of song-poem lies in a timeless and altogether banal scene from family life around a fireplace: El Kanun, where the littlest ones attentively drank in stories from time immemorial, rescued from oblivion by a reassuring matriarch, while the men prepared for the difficult long winter nights and awaited nourishing spring. A single verse might conjure the repeated image of a lost little girl, fleeing the horrible ogre of the night and searching in vain for her father’s protection (a story inspired by the tale of the ogre’s oak). In his liner notes, Mammeri pays tribute to Idir who, he says “endowed his faithful and beautiful verses with modernity and timelessness, using today’s tools to preserve for us an ancient sense of wonder.” On the B-side of the disc, another song is drawn from a book-in-progress by Mammeri called Ancient Kabyle Poems. One legend, “tamacahuts n tassekurt’’ or “tamacahuts n ledyur,” the tale of the partridge, was saved from the oblivion of the page–that half-death that the written word offers to oral tradition– by Idir’s talent. (The story was elevated by modern music, no less pleasant, composed by a medical student named Abderrahmane si Ahmed.) For someone who came to music entirely by accident, once he started there was no looking back. It was the beginning of a great and thrilling artistic adventure for the now-famous singer Idir (as he was known). In traditional Kabyle culture, this name was linked to incantations against, and rejection of, death, and doubtless to the incantations against another death, that of his native culture.

Ancient Poetry as a Resource

Some years later came the publication of the complete collection of ancient Kabyle poems that Mammeri had gathered from the mouths of the last “custodians” of the heritage “before death could snatch them away.” This collection would quickly become bedside reading for young people eager to strengthen the umbilical cord, weakened by state-sponsored identity erasure, that connected them to a language which had miraculously been saved by the extreme resilience of the stories told by its lyric poets, wandering bards and “clear-singers,” amusnaw, and wise men who have been its lifeblood for centuries.

Idir carried the torch forward with his collaborator Ben Mohamed, setting marvelous poems like Mohand Nnegh D’afehli to music and drawing on another poet equally renowned for his output and his almost instinctual knowledge of the life-stuff of ancient poetry: Mohamed Belhanafi, whose celebrated “Azger d yejjanlemtel” (Lesson of the Bull) he borrowed.

After a number of concerts in Algeria and undeniable success, Idir chose to emigrate to broaden his horizons and seize the opportunities that an artistically booming metropolis like Paris had to offer. Another song, “Ssendou,” whose corresponding poem had been written by the poet Meziane Rachid as a kind of lament, was elevated by music as sweet as it was hypnotizing. This completed a panoramic collection of music, largely inspired by the heart of Kabylia’s poetic heritage.

In one of his most recent albums, “At Zik,” Idir undertakes to recreate the atmosphere of agrarian life in the Kabyle of yesteryear by way of poems drawn largely from cultural heritage– what he called in one of his interviews “a foray into ethnology.” In one song he clearly says, in tribute to the ancients, “segayen ilan idelli, is ara d nagwem iw zekka, selt as i ssut n twizi, yetsawi wadu s tazla,” as if to point the way forward for young people and his own contemporaries who have been known to underestimate the heritage of their ancestors–in terms of values–in favor of an artificial, materialistic modernity.

Here, again, an intertextual and indirect parallel can be drawn with one of Mammeri’s famous works, a letter entitled “Tabrats i muhend Azwaw ff tmusni,” which literally means “letter to Mohand Azwaw on the importance of knowledge.” The letter was published in Ancient Kabyle Poems. It is a kind of warning to young generations against being blindly carried away by the allure of a materialist society or rejecting en masse the abstract heritage of their forebears: Ur tsilit ay at ttura, d arrac isedhac ucalwa, yesmenyafen areluc abreqmuc ff uragh yuli ughebar.

Involvement in the identity wars

Public officials banned a conference on ancient poetry (again with ancient poetry!) that Mammeri had been invited to give at the University of Tizi-Ouzou. This brought Mammeri to a boiling point, since “When too much drought burns the heart, when hunger o’er-twists the guts, when too many tears are shed, when too many dreams are muzzled– it’s like adding logs to the pyre. At the end of the day, all it takes is a slave’s scrap of wood to make a towering blaze in God’s heaven and in the hearts of man.” This fire was transmuted into a Berber Renaissance that liberated speech in Algeria and imbued Berber communities in other North African nations with a force of cultural and identity reclamation that was unprecedented in the region. The ripple effect of this movement can still be felt today.

In the agitation that ensued, music emerged as an amplifier for the voices of millions of Amazighs who were discovering the societal, historical and linguistic lineage of their people, which had been scattered by the vagaries of history and the ideological cudgeling of the post-independence powers-that-be. Idir would become an unwitting symbol of this reclamation. He was praised to the skies by the Berbers of his homeland, but also by the Amazighs, now emboldened to create, innovate, and live proudly in their common cultural heritage.

A number of years later, Idir’s appearances at the Tabarka Festivals in Tunisia, or all across Morocco, not only provoked pride and admiration but nourished and created an artistic purpose among the attending troops–even to faraway Azawad, through the group Tinariwen–for the creation of a contemporary Berber music scene. From the hills of Djurdjura, to Jbel N’foussa in Libya, to Djerba in Tunisia, all the way to the high Atlas Mountains of Morocco by way of the M’zab Valley, the Aurès Range, the Chenoua Mountain in Algeria, or even on the Canary Islands, Idir’s voice fed the same hope: to renew filial ties with the land of the ancestors.

Rejecting the trap of ghettoization

When he was asked by the writer-journalist Tahar Djaout (who was assassinated in 1993), about the idea of openness towards others in a book-length interview for Laphomic in 1987, Mammeri recalled the great capacity of the Amazigh to be hospitable throughout their history, then said: “The ghetto may keep us safe, but make no mistake: it also sterilizes!” Made to encounter snares and slander since the publication of The Forgotten Hill in 1952, Mammeri has pursued a variety of avenues of research, refusing to be confined by the narrow horizons that his detractors continually wanted to impose on him. He invoked the history of the Aztecs to better explain the deadly threat that his culture faced, and forged friendships without limits or borders, collaborating with all those who could make research accessible and breathe new life into the rediscovery and reappraisal of the Amazigh language and culture.

This attitude of openness, sharing, and collaboration was almost continuously passed on to Idir from his elder, Mammeri. Indeed, since the late 1980s, Idir has initiated a number of collaborations with foreign artists, particularly those who come from cultures that have been or are currently ostracized by their nations’ central powers. Take for example his duets with the Celtics Alan Stivell and Dan Ar Braz, and his memorable exchange with the Afrikaaner artist and Mandela supporter Johnny Clegg in 1993. Idir duetted with Manu Chao, Jean-Jacques Goldman, Grand Corps Malade, Maxime Le Forestier (several times), and on television with many other artists like Enrico Macias, Patrick Bruel, Yannick Noah, Francis Cabrel, and even posthumously with the great Henri Salvador. The duets were evidence of the immense respect Idir enjoyed among his foreign peers, but also of a conscious desire to break down the linguistic, racial, and musical barriers that might hinder others from fully recognizing his identity.

Getting a global star like Charles Aznavour to sing in Kabyle at age 88 was no mere whim of the average person. In his own way, he standardized the use of Kabyle in international entertainment before Tamazight was even codified (however incompletely) in his own country.

Idir’s thoughtful approach and his conscious desire to advance a cause that was bigger than himself inspired other artists. Today, as Celto-Berber collaborations have popped up in the work of many Kabyle artists, as Finnish or German signers have discovered our music and adopted it, becoming ambassadors of a sort to the rest of the world, the credit goes– as the artists themselves will admit– in large measure to Idir and his tireless and intelligent craftsmanship.

Calm and creativity in the face of adversity

For most, a lifetime would be too short to accomplish what the “twins of the forgotten hill,” Idir and Mammeri accomplished in the space of a few decades. Both men, in their own ways and in their own fields, modeled a constant commitment to their Kabyle and Berber identities, which they claimed in full, without hesitation or a lost measure of pride. Intelligently and without naïveté, fully aware of the risks to their well-being, they made themselves universal for the survival of their ideal. There is no better indication of the cooperation between these geniuses than the mutual recognitions they exchanged. In one letter, Mammeri credits Idir with allowing him to see that “the light of our culture could be so magnificently reignited and so beautifully rendered. You have restored it to its rightful place,” he wrote, “and up in heaven I feel that our ancestors are cascading blessings down on you in the form of stardust.” For his part, the famously restrained singer never missed a chance to pay tribute to his precursor in the reclamation of Berber-Amazigh culture. Idir and Mammeri have been the torch-bearers of an ancestral heritage; they brought its extreme beauty to the ears of the world through emotion and the universal language of music and the heart, and restored the complexity and sustenance of humanity’s common lineage through tireless research and scholarship.

Thanks to these two connector-men, the tales of our grandmothers are no longer held captive in memories of nighttime stories around the fire, and the traveling verses of Si Mohand or Mohand Said Amlikeche or the quasi-Socratic wisdom of Cheick Mohand ou Lhocine are no longer museum artifacts or exotic curiosities, but the lifeblood of a cultural renaissance across North Africa. Out of loyalty to a yearslong friendship, and weighted down by the tragic loss of Mammeri, Idir composed a tribute song of great beauty that will remain for posterity – Amedyaz (The Poet). He would dedicate the last two shows he played in Algiers in 2018– a career epilogue, after an absence of over three decades– to the author of The Sleep of Righteousness.

He also paid tribute directly to Mammeri with these words, which could not make any plainer the immense respect and gratitude that Idir had for the amusnaw:

Wherever you are, Dda l’Mulud, know that here we will always continue to extol your work, and you will remain in our hearts as the man who showed us the well-lit way of our identity. You remain the pride of the Berber people, of the Algerian people, and especially of the Yanni people.

A great African and Berber with the Latinized name Apuleius of Madauros wrote “I am a man, I consider nothing that is human alien to me.” The works of these two luminaries illustrate this kind of openness perfectly. Certainly, they contributed to making “life more human.” Looking down from on high, the ancestors lay upon them “tacdat n laanayansen!” for all eternity.

Works Cited

On Mammeri:

- Mammeri’s preface to the 33 rpm disc of Idir’s “A Vava Inou va.” ( Pathé Marconi- 1976).

- La Colline oubliée (The Forgotten Hill), Paris, Plon, 1952,

- “Les Isefra de Si Mohand ou M’hand,” Berber version and translation, Paris, Maspero, 1969, 1978 et 1982 - Le Banquet (The Banquet), with foreword, la mort absurde des aztèques (The Absurd Death of the Aztecs), Paris, Librairie académique Perrin, 1973.

- Poèmes kabyles anciens (Ancient Kabyle Poems), Berber and French versions, Paris, Maspero, 1980

- “Awal”, Notes on Berber Studies, under the direction of M. Mammeri, with the support and collaboration of the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu and Tassadit Yacine 1985-1989, Paris, - Yenna-yas Ccix Muhand, Alger, Laphomic, 1989.

- Mouloud Mammeri, Culture savante et culture vécue (Knowledge Culture and Lived Culture): (research, 1936-1989), Alger, Tala, 1991, 235 p. Interviews.

- Dialogue sur la poésie orale en Kabylie (Dialogue on Oral Poetry in Kabylia): interview with Mouloud Mammeri -Pierre Bourdieu. Research and Social Sciences. Vol 23, sept 1978. (especially the portion of the interview on the connections between handicrafts and the transmission of Tamusni in the context of ancient Kabyle towns.)

- Du bon usage de l’ethnologie (On Proper Uses of Ethnology): Interview with Pierre Bourdieu- Mouloud Mammeri. Awal. Notes on Berber Studies, n° 1, 1985. - Mouloud Mammeri : Interviews with Tahar Djaout. Published by Laphomic, Algiers, 1987.

On Idir:

- Idir’s discography from 1973 to 2017. Idir’s official website: http://idir-officiel.fr/

- Interview and TV program: IDIR-JOHNNY CLEGG Vis à Vis : “Idir et Johnny Clegg a capella” Un film de Jean-Jacques Birgé, France 3.1993: https://la-bas.org/la-bas-magazine/re...

- Many interviews granted by idir to national and foreign broadcast media (Berbère télévision, France 5, France 2, TV5monde…) and print media ( Paris match, Liberté, El Watan, le Monde…) and radio interviews ( RFI, radio chaine 2, radio tizi-ouzou,Beur Fm…)

- Excerpts from personal correspondence sent by Mammeri to Idir (excerpted from a text sent by Hamid Cheriet (Idir) on February 27, 2009 which was read at the ceremony to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Mouloud Mammeri’s death.

- Le Chêne de l’Ogre (The Ogre’s Oak, a Kabyle fairy tale in Le Grain Magique, Taos Amrouche), Paris, published by Maspero 1966. To listen to the story read out loud: https://youtu.be/vZcHD36fFhw

My personal references:

- Informal interview and radio interview with the poet Benmohamed for the program Timlilitimazighen-radio centre-ville, Montreall, December 2019.

- Informal discussions with the poet Mohamed Benhanafi (radio chaine 2) 1997-2005.

Mammeri’s preface to the 33 rpm disc of Idir’s A Vava Inou Va (released in 1976)

Outside, snow blankets the night. The banishment of the Sun has drawn out our fears and our dreams. Inside, a raspy voice, the same for many centuries, millennia, that of our mothers’ mothers, creates the marvelous world that our ancestors were raised by for many long years. Time stops, music drives away fear and ignites the warmth of man near to the warmth of the fire. The same rhythm weaves the wool for our bodies and the fable for our hearts. So it has been forever, yet these last dying nights threatened to take the last rhythms with them. Will we remain their orphans? We must show gratitude to the one who endowed his faithful and beautiful verses with modernity and timelessness, using today’s tools to preserve for us an ancient sense of wonder. The snow blankets the night, but in vain.

Mouloud Mammeri.

How to Cite:

Ikken, D. at/Amrani, D., (2024) “‘Idir et Mammeri: From the particular to the Universal: Two Cultural Ambassadors Cross Paths”, Tamazgha Studies Journal 2(1), 66-72.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 2 • Issue 1 • Spring 2024

Pages 66-72

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Montreal