Essays

Between Boston and At Yenni: Two Musical-Cultural Journeys

AUTHOR: Jane E. Goodman

Between Boston and At Yenni: Two Musical-Cultural Journeys

Jane E. Goodman

Indiana University

Abstract: Memoir-style narrative about how the author discovered the music of Idir and what it meant to her personally as she traveled to Kabylia in the early 1990s, where she encountered the larger Amazigh identity movement that Idir’s songs heralded as well as the songs of the village women who inspired Idir. The author sets her reflections about Idir’s music alongside an account of her own emergence as both a scholar of cultural anthropology and a singer with the Boston-based women’s group Libana. These diverse actors were similarly engaged in what would become a global impulse to find inspiration in women’s traditional songs.

Keywords: world music, anthropology, musical encounters, transcendence

I gave my first talk about Idir’s music at an Amazigh event held at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the late 1990s, when I was still in graduate school. I spoke about the ways Idir drew songs and stories from old women (temgarin) of Kabylia into his songs, cloaking traditional images in a contemporary musical language. After the talk, a Kabyle audience member came up to me. “I didn’t know we had all that in our music,” he remarked.

“All that in our music.” What was the “all that”? What was it about Idir’s songs that allowed them to travel so widely? What made them speak to so many audiences? Since Idir’s untimely passing in May of 2020, I’ve written and spoken about his hit A Vava Inou Va, about the New Kabyle Song (la nouvelle chanson Kabyle) movement that he helped to launch, and about the confluence of art and politics that made his music possible. During my research in Algeria in the early 1990s, I explored some of the major influences on Idir, including the 1969 PanAfrican Festival in Algiers. I read the ethnographic work that French anthropologist Jean Duvignaud had carried out in the Tunisian village of Shebika, which was documented in Bertucelli’s film Ramparts of Clay. In the early 1970s, Duvignaud had spoken about his work in Shebika at the French Cultural Center in Algiers: this talk inspired Idir’s collaborator, the poet Ben Mohamed, to write the verses of A Vava Inou Va. I had situated Idir’s work in relation to Amazigh cultural and linguistic politics in Algeria. And eventually, I studied Idir’s song texts line by line and word by word, going back and forth between his versions and the village women’s songs that inspired him (Goodman 2005). But I have never written about how Idir’s songs affected me, nor about the ways Idir’s musical trajectory intersected with my own.

I first heard Idir’s music when an Argentinian friend living in Paris mailed me a cassette compilation (precursor of the playlist) of some of the songs that were popular in France at the time. Along with music by his favorite nueva canción artists like Mercedes Sosa and Silvio Rodriguez was a new hit that had started climbing up the French charts: A Vava Inou Va. At the time I knew nothing of the Imazighen and not much about Algeria, but I liked the song. Though I didn’t understand the lyrics, the music drew me in. It was smooth, singable, flowing. It was simultaneously familiar and evocative of an “elsewhere.” It was a bridge, offering a glimpse of another place in a musical idiom that resonated with me.

Around the time that I received the tape, I had started singing with Libana, a world music ensemble in the Boston area that had recently formed to explore the music of women of other cultures. We were curious: What were women around the world singing about? How could we learn to sing the way they did, using our vocal apparatus to create the bright, piercing resonance of Balkan Mountain songs or the sultry, lyrical airs of the Middle East? What were the contexts in which women made music together? We would rummage through the record bins at the Harvard Coop in the days before “world music” was even a thing, looking for music by women from other cultures. I can still picture the cover of the album I found of music from Iran. It intrigued me, and I bought it. One of the songs caught my ear, and I played it for our artistic director, Susan Robbins. We decided that we wanted to learn sing it, but we didn’t speak the language. We put out feelers to our growing network and found an Iranian woman willing to help us. So it was that one grey Saturday morning found me venturing out, cassette recorder in hand, to her home. I played the song for her over tea, and she spoke the words for me, slowly, into my tape recorder so Libana could work on the proper pronunciation. She no doubt told me what she knew of the song’s meaning and cultural context, and I brought all of that back to Libana. And so it was for songs from Bulgaria, Albania, the Georgian Republic; from Armenia and Ukraine; from Lebanon, Croatia, Egypt, and so many other places. A few years later, we would sing several women’s songs from Algeria (though we did not sing Idir’s music).

Idir, it turns out, was engaged in a similar pursuit on the other side of the Atlantic. Unlike Libana, of course, he was working within his own cultural tradition. But all of us were seeking out the cultural knowledge and beauty that we saw in women’s traditional repertoires. All of us were coming to value women’s songs in new ways. All of us were going to women to find out what they were singing, and to see how we could bring their songs into our own voices and out to new audiences. Nor was it just Idir and Libana. We were all part of what was apparently a burgeoning passion for what is now called world music—though in the pre-internet days of the early 1980s, we lacked any way of knowing how big this new trend was becoming. With my anthropologist’s hat on, I knew all of the ways this kind of venture could be problematic. I understood that it was only from the perspective of modernity that we could constitute something called “tradition.” I knew the ways this could romanticize women, the ways it could homogenize them, the ways we could be understood to be appropriating songs that were not ours. I also knew that some Kabyles were raising similar questions about the new Kabyle singers, mostly male: that they were appropriating women’s repertoires, in many cases (though not Idir’s) without attribution.

But I also knew that in discovering and performing these songs, we felt a profound connection to an elsewhere, a desire to move beyond the limitations of our own cultural backgrounds. As I performed what we now call world music with Libana, my heart opened in ways that it has never opened as an anthropologist. For Idir, perhaps it was similar. Performing allows us to transcend ourselves, suggesting other ways of being, perhaps providing an opening to what the theater scholar/practitioner Jill Dolan calls a “performative utopia.” I experienced that transcendence as a performer myself. And I also experienced it in listening to Idir’s music.

When I started graduate school in anthropology, I had no plans to do research in Algeria. But as an undergraduate I had spent several years in southern France, where I had first gotten to know Algerians. As a graduate student, I became curious about their country. And I remembered Idir. When I began my doctoral research, I worked with a number of New Kabyle Song artists, including Lounis Aït Menguellat, Ferhat Imazighen Imula, and Matoub Lounes. But it was Idir’s music that I would repeatedly come back to. It was Idir’s music that I would put on when I was alone at night in the small Kabyle house (axxam) that my host family had graciously allowed me to live in. By then, I knew the lyrics and could sing along. His songs anchored and transported me with their lyrical beauty. Idir’s music helped me to feel at home in a remote mountain village that (at the time) did not even have a landline connection to the wider world.

While in Kabylia, I had the good fortune to travel to Idir’s natal village At Lahcen (At Yenni). This was in 1993, and the older women in the village had known Idir since he was a child. I told them I was interested in how he had transformed their songs. Together, we listened to Idir’s recordings, and then they would sing their traditional versions of the songs for me. I recorded their singing on my Marantz cassette recorder (still the medium of choice in the early 1990s). We talked about what their songs meant to them and about what they thought about Idir’s transformations. Back in Paris, I met several times with Idir. We sat talking about his songs in the Kabyle café across from the Association Culturelle Berbère in Ménilmontant. In Paris, I also worked extensively with Ben Mohamed, the lyricist for many of Idir’s early songs. Over many long dinners, Ben and I talked about the changes he and Idir had made to the texts to allow the songs to speak to contemporary times while also evoking Kabyle traditions. Ben, too, worked from a cassette he had gotten from a friend of an old woman (tamgart) singing the songs of her village.

The recordings I made in At Yenni and heard in Ben Mohamed’s living room stayed with me. They resonated with the musical and cultural journey I had taken in Libana. In Libana, too, we would seek out women from other cultures to teach us their songs. We would compile our own cassette “playlists” that we would listen to over and over, trying to find just the right vocal sound, just the right pronunciation, so that we could transport these songs to our audiences and in turn transport them to another world. Idir’s process had been similar to our own. He, too, imitated Kabyle women’s ornamented style of singing. He, too, brought their songs to new audiences. He, too, transported so many of us.

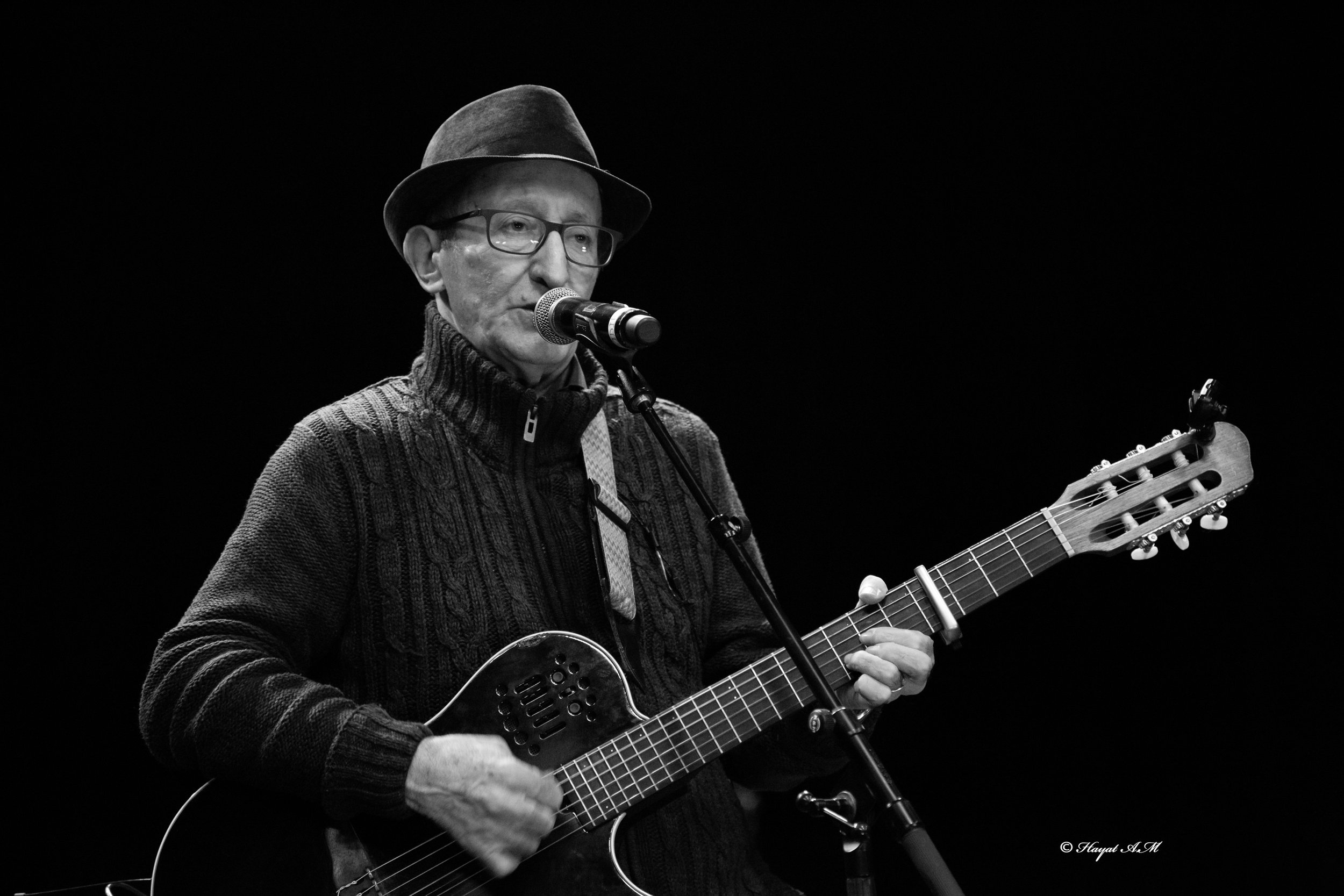

When I heard Idir at the Olympia Theater in Paris, I was sitting with several singers from the group Djurdjura—a Kabyle women’s group inspired by Idir. (I had met Djurdjura after Libana had come across their music; we had performed several of their songs with founder Djoura Abouda’s help and permission.) Idir closed the Olympia concert with A Vava Inou Va, inviting all Kabyle singers present at the concert to join him onstage. The Djurdjura women leapt from their seats and hurried down to the stage, joining several dozen singers who passed the microphone from one to the next (in retrospect, I wish I had gone with them!). It was moving to see all of them coming together to sing with Idir on what by then had become a Kabyle anthem. At the Zénith Theater several years later, Idir again ended with A Vava Inou Va, this time pointing his mic at the crowd to allow them to carry the tune. As we walked out into the cool summer night, some of us boarded a Parisian bus, and the air began to resonate as the passengers—many of them young people who wouldn’t even have been alive in 1973 when the song was released—together intoned the chorus of A Vava Inou Va.

The development of what we now call world music—understood, per the anthropologist Steven Feld, as a “marketing category” with “commercial potential” that was associated with works like Paul Simon’s Graceland (1986) and David Byrne’s Rei Momo (1989) (Feld 2000, 149)—started to accelerate in the 1980s.[1] But a decade earlier, Idir had been going back to his village to recover and revitalize the songs the old women knew. A decade earlier, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Libana had also been going into the living rooms of local women from far-flung places, seeking out musical encounters. What would become a worldwide phenomenon was born not (or not only) as a marketing category but as a quest for human connection through music—a quest that brought Libana into the homes of our extended community and Idir to the hearths of his home village.

If Idir transformed women’s songs, the impact of his music was transformative for Kabyles and Algerians. It was also transformative for a young American woman living in Boston when she first heard his songs. I had to become an anthropologist to write about Idir. But that writing does not convey how his music touched and opened my heart. Idir’s music transported me. I am forever grateful.

References

Bertucelli, Jean-Louis. 1970. Remparts d’argile (Ramparts of Clay), dir. J.-l. Bertucelli. Tunis, Tunisia: Office Nationale de Commercialisation de d’Industrie Cinématographique (ONCIC), 85 mins.

Dolan, Jill. 2005. Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope at the Theater. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Duvignaud, Jean. 1970 (1968). Change at Chebika: Report from a North African Village, trans. F. Frenaye. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Feld, Steven. 2012. Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra: Five Musical Years in Ghana. Duke University Press.

_______. 1988. “Notes on World Beat.” Public Culture 1(1):31-37.

Goodman, Jane. 2005. Berber Culture on the World Stage: From Village to Video. Indiana University Press.

Footnotes

[1] See also Feld’s more recent book about his five-year musical collaboration with Ghanaian musicians (Feld 2012).

How to Cite:

Goodman, J. E., (2024) “‘Between Boston and At Yenni: Two Musical-Cultural Journeys”, Tamazgha Studies Journal 2(1), 58-61.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 2 • Issue 1 • Spring 2024

Pages 58-61

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Indiana University

Keywords: world music, anthropology, musical encounters, transcendence