Peer Reviewed Article

Recording Lightning: Popular Music and the Amazigh Cultural Movement of the 1970s

AUTHOR: Ben Jones

Recording Lightning:

Popular Music and the Amazigh Cultural Movement of the 1970s

Ben Jones

Georgetown University

Abstract: In the mid-1970s, the Moroccan band Ousmane (whose name means ‘lightning’) became the first group to record popular music in Tamazight, the Indigenous language of North Africa. Combining local folk music with new musical technologies and an explicit political platform of Indigenous rights, the band promoted Amazigh rhythms and styles as essential aspects of Moroccan national culture. On vinyl records and in concert halls from Casablanca to Paris, Ousmane pioneered a hybrid musical genre which sought to reconcile “authentic” Indigenous traditions with “modern” and “scientific” musical principles which they saw as necessary for political and social progress. Amidst the turmoil of what came to be known as the Years of Lead, questions of Moroccan national identity were heavily contested. Ousmane’s own story puts these conflicts between official political discourses and popular movements into stark relief, revealing the complex ways in which musicians navigated colonial legacies and cultivated modern audiences. Through an examination of archival documents from the Moroccan popular press of the 1970s and Ousmane’s own musical output, this article argues for the utility of popular music as a source for narrating subaltern history in the 20th century.

Keywords: band Ousmane; Morocco; Morocco; Amazigh music; Years of Lead.

Introduction

In February 1977, the Moroccan band Ousmane took the stage at L’Olympia Theatre, one of Paris’s largest and most historic venues. The performance that night, part of a 1977 tour of France and Belgium alongside the influential Moroccan bands Nass el Ghiwane and the Megri Brothers, was recorded live and released as an LP by the Maghrebi label Boussiphone, marking the artistic and intellectual peak of Ousmane’s career. The band “brought Tamazight art to the heart of France for the first time,” reported one Moroccan newspaper. “This earned them the respect of the public and the praise of the French press.”[1] The band’s lead singer, Mbarek Ammouri, would later tell the same paper “we are very satisfied with this contact with an audience whom we love enormously and who loves us for the authenticity of what we offer them, far from anything commercial or folkloric.”[2]

What was this musical “authenticity” that Ousmane possessed, and why did their audience clamor for it so enthusiastically? In the tumultuous cultural politics of the Years of Lead (as the repressive reign of King Hassan II was dubbed) these questions cut to the heart of a contested Moroccan national identity. Ousmane was at the leading edge of the Amazigh Cultural Movement (ACM), which rejected the state’s Pan-Arab ideology and emphasized Indigenous representation and cultural autonomy. The band’s success in both Europe and Morocco reflected popular dissatisfaction with the reigning cultural and political establishment. Close listening to the song “Dounit,” which was recorded live that night in Paris, lays bare the conflicts between official discourses and popular movements, revealing the complex ways in which musicians navigated colonial legacies and cultivated modern audiences. Through a social history of the Indigenous music movement in Morocco, this paper argues for the utility of popular music as a source for narrating subaltern history in the 20th century. Although as yet little acknowledged in national historiography, Ousmane’s musical activism in the 1970s paved the way for more mainstream representations of Amazigh culture in contemporary Morocco, on behalf of both the state and its critics. The band used their music to open a debate on Moroccan national identity which has yet to be settled.

Literature Review: Listening to North African History

Historians of modern Morocco have long contended with Orientalist legacies and nationalist mythologies in documenting the complex and overlapping forces of nationalism, political consolidation, and identity formation in the postcolonial period. Much scholarship continues to reproduce the same worn-out binaries of the colonial period (modern vs traditional, oppressed vs oppressor, Arab vs Berber) in explaining recent history. Compounding these problems is scholars’ continued reliance on official government archives to write the history of North Africa. As Susan Gilson Miller argues, historians’ focus on the role of the monarchy and the Istiqlal party in the nationalist project has silenced marginalized groups and obscured the continuities between the colonial and postcolonial periods.[3] To counteract these “teleological” discourses, Driss Maghraoui calls for Moroccan history to “be freed from the political and ideological constraints” of nationalism and Orientalism through the use of “more local history, orality, search for subalternity [and] ‘unconventional sources.’”[4]

Where is history to be found, if not in state archives? In his work on media-capitalism, Ziad Fahmy makes a forceful case for vernacular sources to fill the gaps in traditional political histories. Rather than situating the origins of nationalism in newspapers, novels, and other texts written in standard Arabic, as scholars following Benedict Anderson’s approach have often done, Fahmy examines how the urban masses of Egypt have alternately accommodated and resisted elite print discourses through the vernacular world of music, theater, and film.[5] Many scholars have demonstrated the utility of such sources in unearthing subaltern perspectives and counter-hegemonic discourses. Indeed, some claim that music is a uniquely important source because “more than any other cultural product, music is ‘aesthetically embedded’ within—reflecting and even amplifying—the larger social, political, and economic dynamics of a society, and political and economic power inevitably have an ‘aesthetic property.’”[6] These scholars argue that music is key to understanding political processes of state formation and identity consolidation.

A small but growing body of scholarship has begun applying these concepts to North Africa, where the existence of a large Indigenous Amazigh community further complicates the writing of cultural history. In his groundbreaking book Recording History, Christopher Silver uses “a world of physical, visual, and audible musical documents” including records, leaflets, and concert posters to explore the connections between popular music and state formation in North Africa between 1900 and 1960.[7] He not only elucidates the key role that popular musicians played in the anti-colonial movement, but also challenges notable preconceptions by demonstrating a culture of Muslim-Jewish cooperation in the North African recording industry. In the same vein, in Moroccan Other-Archives Brahim El Guabli argues that it is necessary to struggle against the silencing of Indigenous voices by “creating archives where there are none and writing histories in which loss and silence occupy the place of archival sources”.[8] He draws upon numerous unconventional sources, including Indigenous place names, novels, and oral testimonies to write a history of post-colonial Morocco that official archival sources have ignored and silenced.

This study of Ousmane contributes to the above literature in two important ways. Taking inspiration from Silver’s reading of vinyl records as instances of material culture that encode information both in their grooves and through their artwork, this paper carries the history of Moroccan popular music forward into the postcolonial period with a particular attention to the growing importance of Indigenous artists and culture in articulating national identity. It also serves as a corollary to El Guabli’s textual analysis of the Amazigh movement. El Guabli focuses on the intellectual progenitors of this movement and the novels and poetry they published in Tamazight; he praises the alphabet they produced, Tifinagh, as a “vital force [...] disrupting the linguistic order and driving a wedge between languages of foreign powers [Arabic and French] that colonized North Africa.”[9] Yet in the 1960s and ‘70s the overwhelming majority of Tamazight speakers were illiterate, and despite the language’s growing acceptance in official spaces it remains much less read than Arabic and French even today among Indigenous Moroccans. Thus this study follows Fahmy’s attention to vernacular sources by analyzing how popular bands like Ousmane translated the Amazigh movement’s goals for a wider audience. In doing so, this article hopes to focus attention on the centrality of Indigenous issues in the modern history of the Maghreb.

Colonial Legacies in Moroccan Cultural Politics

French forces invaded the eastern Moroccan city of Oujda in 1907, initiating a period of colonial rule that would last almost fifty years. After thirty years of nearly continuous warfare, the Protectorate, the innocuous name for France’s clientelist relationship with the ruling Alawi Sultanate, would come to encompass a large area stretching from the Atlantic coastal plains of Casablanca and Rabat through the mountains of the Middle and High Atlas and into the pre-Saharan oases of the Drâa Valley. The rugged and inaccessible nature of much of this territory had historically enabled many communities, representing a diversity of languages and cultures, to enjoy a great deal of autonomy from the central government. While Arabic language and culture were associated with urban centers like Fes and Rabat, Indigenous communities in the Atlas Mountains and pre-Saharan valleys spoke a wide variety of Tamazight dialects. In this complex multilingual environment, ethnic identity could rarely be simplified to ancient affinities of kinship. This diversity was reflected in a vast array of interrelated musical styles. Although many of these genres were often associated with particular regions, such as the Arabophone ‘ayiṭa of rural Doukkala, the classical Andalusi music of urban Fes and Oujda, and the Ahidous dance of the Middle Atlas, they shared many common features and instruments.

In encountering the enormous diversity of this territory, French officials set about categorizing and demarcating the populations now under their rule. From the beginning, colonial policy was justified by a scientific discourse which theorized “a profound ethnic split in Moroccan society between Arabs and Berbers.” This “colonial vulgate,” originating from France’s century long settler-colonial experience in neighboring Algeria, was sustained by a body of linguistic, geographic, and ethnographic research which characterized the Indigenous populations of North Africa as rebellious mountain warriors, locked in an eternal struggle for political and military supremacy with the urban Arab ruling class.[10] Moroccan territory was divided into governed and ungoverned zones (blad al-makhzen and blad as-siba), with the Indigenous inhabitants of blad as-siba understood as being racially and culturally predisposed to revolt. With the final ‘pacification’ of Morocco accomplished in the 1930s, the imagined divisions between ‘Arabs’ and ‘Berbers’ became reified in a set of policy decisions through which French officials attempted to divide and rule the colonial population. The colonial education system sorted out and assigned students into separate Arab, Berber, and Jewish schools. Sons of rural dignitaries attended the Collège Berbère in the Middle Atlas town of Azrou, where classes were taught in French.[11] This segregationist classification policy, imposed on a staggeringly diverse social reality, facilitated colonial control of Moroccan territory and population.

Imagined colonial demarcations also extended into the realm of cultural policy. Colonial rule was justified through a philosophy of cultural preservation and enlightenment, France’s famous mission civilisatrice, and to that end Resident General Hubert Lyautey established a Service des arts indigènes as early as 1928. The Service trained and promoted local musicians, presenting Arab and Berber genres as essential components of Morocco’s “two civilizations.”[12] In regards to the Andalusi classical tradition, Jonathan Glasser shows how this music “came to be an arena for the exertion and contestation of sovereign power.” In 1939, the protectorate organized a congress of Andalusi musicians in Fes to discuss and perform the genre. The goal was nothing less than to “save the Moroccan soul in its most subtle and powerful form of expression.”[13] Tamazight language music was conceived of as a unifying element in rural regions, with Service director Ricard Prosper organizing a “Chleuh ensemble” to tour 26 Moroccan towns between 1928 and 1931. Colonial cultural policies were characterized by a “continued anxiety toward hybridity,” with French ethnographers attempting to record and preserve various ‘Arab’ and ‘Berber’ traditions before they were contaminated by either Western influence or pernicious intermixing.[14]

These divisive social and cultural policies culminated in 1930 with the so-called ‘Berber’ Dahir, which announced that certain rural populations would be governed by tribal councils according to local customary law rather than the Maliki Sharia law applied in the rest of the country. Incensed urban intellectuals rallied in opposition to the Dahir. In response to divisive French policies, the nationalist movement demanded a reformed protectorate founded on the twin pillars of Islam and the Arabic language, framing “the legal, administrative, and educational components of the French Berber policy as a lethal threat against the unity of the Moroccan umma, subtly transposing an imagined ethnoreligious national political unit onto pre-existing notions of Muslim collective identity.”[15] The furious reaction to the Dahir led colonial officials to quickly retract the policy. The episode, however, had a profound effect on the course of the nationalist movement and post-independence state. The events of 1930 “represent a foundational event in the unfolding story of Moroccan nationalism, satisfying the need for ‘a myth of origin’ from which a linear history of the nation could evolve.”[16] Paradoxically, the urban elites who led the Moroccan nationalist movement had staked their solidarity with rural communities on a denial of the linguistic, ethnic, and political differences of the country’s population. This would pave the way for a homogenizing policy of Arabization following independence.

The Moroccan nationalist movement reached its climax after World War II in a campaign of protests, bombings, and armed resistance. France, facing an even more serious conflict in Algeria, granted independence in 1956 to a government led by King Mohammed V and the nationalist Istiqlal Party. These elite groups were invested in a shared vision of Arab-Islamic identity for the new Moroccan state. One of the regime’s first actions was to revoke the 1930 Dahir. On July 13, 1956, the king gave a speech in the Middle Atlas town of Khenifra, long considered a homeland of Amazigh identity, to a crowd of 100,000 in which he officially abolished the Dahir and laid out the state’s new vision for Moroccan identity:

Since Islam spread its light in this country, it has cemented the union of its inhabitants and made a strong and united nation that no force in the world could divide, a unity that has been written in history for more than thirteen centuries. Our people, placed in the shadow of Islam, tolerating no discrimination between Arabs and Berbers, and with no other ideal than its love of nation, are an example of solidarity and brotherhood. It is this union that has made of us a glorious nation, which allowed our ancestors to found an empire so vaunted in history. For you there was only one homeland, only one nation, and only one throne.

With this symbolic act, the state completed “the framing process urban nationalists had begun in the 1930 Latif protests that unified Moroccan national identity around the concepts of Islam, patriotism, and loyalty to the Alawid throne.”[17] Under these banners, the state attempted to simultaneously distinguish itself from the old colonial regime and to refute that regime’s divisive Berber policy by asserting Arab-Islamic unity. In the years after 1956, the monarchy would institute a policy of Arabization which violently elided disparate regional, Indigenous, and hybrid identities that were seen as threatening to national unity.

In a refutation of colonial policy, Arabic was declared the official language of the state and the only mode of instruction in government schools, including the Collège Berbère in Azrou. The Ministry of Education set the ambitious goal of replacing all French-language instruction with Arabic within three years; because of a shortage of qualified teachers, Arabic speakers had to be recruited from abroad.[18] This policy was deeply ambiguous and ultimately unattainable, due to a lack of ideological and financial commitment. Brahim El Guabli has argued that these policies’ primary effect was not to replace French but rather to dislodge Tamazight from public life.[19] Outside the classroom, Arabization was pursued at a number of other levels, including a 1961 fundamental law which declared Morocco to be an Arab and Muslim state in which the national language was Arabic.[20] As late as the 2000s, a Civil Registry requirement that given names have a “Moroccan character” effectively prevented parents from giving their children Amazigh first names.[21] The regime’s pressures on Tamazight mean that few written works were produced in the language, leading to an invisibility of Indigenous issues that has been exacerbated by scholars’ reliance on texts written in French and Arabic. The cumulative effect of these Arab nationalist policies was to marginalize and minoritize Tamazight speakers, effectively presenting them as a cultural Other in need of assimilation to a post-colonial Arab modernity led by the monarchy.

Even for historians intent on accessing sonic histories, it can be difficult to locate the voices of Indigenous artists. Rural folk traditions before the 1970s, regardless of their cultural origins, had largely been excluded from the official channels of Moroccan popular music. Cultural prestige and commercial viability was accorded to classical Andalusi music, or to the orchestral styles of the Egyptian superstars like Oum Kulthum, Mohammed Abdelwahab, and Farid El Atrash who usually sang in standard Arabic.[22] In the place of Sufi ritual music like that of the Gnawa, Jilala, and Hamadsha orders, whose inclusion of trance states in religious practice was considered improper and un-Islamic, the monarchy sponsored nationalistic music performed in an unmistakably Arab idiom. One musical champion of the monarchy was Samy Elmaghribi, a Jewish singer from Safi. Elmaghribi rose to prominence in the 1950s and powerfully linked his own image with that of the monarchy through a series of concerts for the Sultan and the Crown Prince held on Throne Day. His songs, usually performed in Andalusian or Egyptian styles with an orchestra of violins, accordions, and saxophones, praised “the brave of the Rif and Atlas [Mountains],” citizens “from Agadir to Fez,” and those who “come from the cities and the hinterland to delight in your Throne Day.”[23] The nationalism of songs like Elmaghribi’s glossed over regional differences with patriotic waltzes and classical tunes aimed at all audiences.

The Moroccan Left of the 1960s and 1970s

Although the rhetoric of the post-independence Moroccan state suggested a radical rupture with the colonial past, this merely served to obscure simmering class tensions and the ongoing marginalization of rural and Indigenous communities. In attempting to assert a unified Arab-Islamic identity, nationalist policy makers shared with their French predecessors an oversimplified picture of Amazigh people as primitive and fundamentally alien to Arab culture. However, these assumptions were soon challenged from multiple sides in a postcolonial intellectual and cultural flourishing. Socialist and Marxist groups in Morocco shared column space in opposition journals with a growing movement for what would later be conceived of as Indigenous rights. At the same time, working class young men in Casablanca led a revolution in Moroccan popular music by incorporating Indigenous instruments and valorizing rural aesthetics, thereby creating a new genre known as the “Band Phenomenon.” Together, these disparate strands of countercultural activism would produce Ousmane in the mid 1970s.

Beginning in the 1960s, Moroccan intellectuals led an artistic renaissance in response to the stultifying influence they perceived in official cultural production. Having been radicalized by the anti-colonial struggle and disappointed by the repressive politics of the new kingdom, opposition thinkers coalesced around left-wing journals like Souffles (later published in Arabic as Anfas) and Lamalif. In the pages of these journals, Moroccan writers called for ‘authentic’ poetry, novels, songs, and graphic art which would merge modern and traditional aesthetics. “The call for the authentic was to become a constant, almost identifying, feature of these journals,” writes Gonzalo Fernandez Parilla, “implying that the lack of authenticity was located in the institutional realm.”[24] Many of these leftist intellectuals idolized Frantz Fanon, who argued in The Wretched of the Earth that “national culture [...] must lie at the very heart of the national liberation struggle.”[25] Resurrecting authentic popular heritage and building a new national culture thus became political imperatives for the new generation living in the shadow of anticolonial struggle and postcolonial repression. “Only a mental reforging, a rediscovery of our heritage, a questioning and reorganization of this heritage can allow us to take the reins of our personality and destiny as human beings,” Souffles founder Abdellatif Laâbi declared in 1966.[26] Such militant rhetoric put Morocco’s contested national identity at the heart of postcolonial political debates. It was threatening enough that in 1972 the state arrested Laâbi and shuttered his journal.

Yet despite these radical stances, most opposition thinkers of the 1960s and ‘70s glossed over the debates around Indigenous identity raised in the colonial era. There was heated debate about the relative merits of publishing in French or Arabic, but no serious consideration of Tamazight as a language of public expression. Many of the writers were avowed Pan-Arabists, and these commitments were often expressed in a certain attitude of Maghrebi exceptionalism. “The Arab world has always constituted a unified cultural and spiritual entity” Laâbi explained in 1966. “The multiplicity of autochthonous dialects in each country of Black Africa as well as the lack of unified and transcribed vernacular languages have prompted writers to resign themselves to the use of foreign languages. In the Maghreb, where the language of culture has for centuries been Arabic, the issue is much more complex [...] it is certain that the destiny of the Arab people has long been interwoven with the evolution of Arabic, its language of expression.”[27] For much of the 1960s and ‘70s, the debates over Morocco’s various connections to Arab, African, and French culture failed to recognize the country’s Indigenous heritage and obscured the ongoing state-sponsored marginalization of Indigenous people.

Despite the notably Pan-Arab overtones of much of the writings in Souffles and Lamalif, the journals’ populist commitments gradually produced growing calls to study oral, vernacular, and rural forms of Moroccan culture. There was a certain irony in the many debates over French vs. Standard Arabic in a country where the vast majority of the population could not in fact read either language. “The triumph of so-called national culture was really just that of the petit bourgeoisie. And, also, the triumph of urban, orthodox, puritanical Islam over the fundamentally mystical Islam of the peasant masses,” the philosopher Abdelkebir Khatibi told one interviewer in 1973. “That is why, when we speak, we must ask ourselves whom we’re addressing. Will we drone on about the same themes that the nationalist elite has allotted to us, or, rather, systematically begin new analyses—this time starting with repressed popular culture, with popular aspirations? If we want to speak differently, we must listen to the people and their repressed culture.”[28] While these calls rarely addressed Indigenous heritage directly, the attention to “repressed popular culture” attempted to capture specificities of Moroccan culture that distinguished it from other Arab nations in the Mashriq. Some authors began advocating for Moroccan darija as an authentic language of national expression. Translations fail to capture the “subtlety of allusion and the characteristically Moroccan flavor of [our] tales and popular legends, giving only a very vague, not to say false, idea of the true nature of popular poetry in Maghrebi dialects,” wrote the film director Ahmed Bouanani. “Classical historians and biographers dismiss anything not composed in literary Arabic, casting into oblivion these “vulgar and illiterate poets,” who nevertheless have expressed the deepest sentiments of our people.”[29] Although Bouanani was not specifically discussing Indigenous culture (the word ‘Berber’ appears only twice in the article) many of the rural, oral traditions he mentions are in fact Amazigh in origin. “Vulgar,” “illiterate,” and “vernacular” were epithets that could be applied to the country’s rural population, whether Arab or Amazigh, who had long been excluded from official cultural platforms. The growing calls to examine these marginalized groups laid the groundwork for future Indigenous activism.

One of the only thinkers of the Moroccan ‘60s generation to pay serious attention to Amazigh culture was Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine, a poet from the Soussi town of Tafraout. Often described, along with Khatibi, as a “linguistic guerrilla” for his aggressive experimentation with French literature as a form of resistance, he began his career publishing French poetry in the early editions of Souffles before turning to novels with increasingly Indigenous themes and content.[30] As one of the few Indigenous members of the intellectual scene that had coalesced around Souffles and Lamalif, Khaïr-Eddine took that generation’s focus on vernacular and popular culture to one of its logical conclusions. His work serves as a bridge between the debates over national culture that were waged in the pages of Morocco’s cultural journals in the 1960s and ‘70s and the subsequent development of the Amazigh Cultural Movement.

Nass el Ghiwane and Radical Folk Music

The call for a revival of Moroccan culture was answered by a group of young men from the working-class Casablanca neighborhood of Hayy Mohammedi. In early 1970, a band called Nass el Ghiwane began experimenting with a new style of popular music grounded in the traditions of rural Morocco. They blended together regional genres like ‘ayiṭa and Gnawa into a folkloric pastiche that spoke to audiences across post-colonial Morocco. Sung in a dense and rustic style of Moroccan Arabic, their songs evoked nostalgia for rural Moroccan communities that had been devastated by export-oriented colonial land expropriation and economic reforms.[31] One newspaper compared an early Ghiwane performance to electroshock therapy, writing that upon hearing this new popular music “you feel the urge to dance hysterically, take off your clothes, pull out your hair and shout from the depths of your heart as it burns with heartbreak and pain.”[32] Moroccan listeners connected fervently and intensely with Nass el Ghiwane’s new musical style, building a new kind of social and musical phenomenon.

Nass el Ghiwane’s use of sounds from various folk styles was more than just a skillful musical innovation. Their presentation of folk instruments on the country’s television channels, record labels, urban cabarets, and even the royal palace itself also constituted a political statement on the value and artistry of native folk cultures in modern Morocco. Traditional acoustic instruments, associated with beggars and village peddlers, had been deemed unworthy to be played for the public or recorded in the elite urban culture of post-colonial Morocco. “These instruments were unknown and audiences viewed them skeptically,” lead singer Larbi Batma recalls in his memoir, “for they were usually only played in homes and women’s parties.”[33] The folk instruments used by Nass el Ghiwane were disdained for their use by street performers and lewd female dancers, unlike the “modern” instruments of Andalusi and Egyptian music like the violin, oud, and accordion. Band member Omar Sayed spoke about overcoming the shame associated with these instruments in the band’s first public appearances. “Some musicians were ashamed to perform the type of music we did in front of an audience,” he told one interviewer, “But we found no fault in carrying the bandir and the dadou’. We were the first [popular] band to play al-maqām al-khāmis (a folk music rhythm) […] we destroyed the barriers of shame.”[34] In proudly carrying Indigenous instruments on the country’s biggest stages, Nass el Ghiwane advanced a program of “heritage research” which challenged decades of social and cultural policies that had sought to erase these traditions from Moroccan life.[35]

Nass el Ghiwane’s success quickly inspired countless imitators. Two musicians who had taken part in Nass el Ghiwane’s first performances around Casablanca left the band in 1971 to form their own group, Jil Jilala. Together, Nass el Ghiwane and Jil Jilala pioneered a new genre which came to encompass innumerable bands with their own variations on the Ghiwani neo-folk model. Dozens of bands sprang up across Morocco. Critics variously identified this cultural movement as Dhahirat al-Mujmu’at (the Bands Phenomenon), al-Dhahira al-Ghiwaniyya (the Ghiwani Phenomenon), or more simply al-Dhahira (the Phenomenon). It was within this wave of musical production that Ousmane would emerge in 1974 as the first Tamazight-language popular music group in Morocco.

The Amazigh Cultural Movement

Around the same time as leftist intellectuals and upstart musicians were beginning to critique the postcolonial state’s conception of Moroccan identity, Indigenous scholars and activists were laying the seeds for what would become the Amazigh Cultural Movement. Although French policy had long put Arab and Berber identities at the center of colonial politics, the Arabization policies of the region’s postcolonial states gave new urgency to the struggle for the recognition and support of Indigenous communities. In 1966, a group of mostly Algerian émigrés led by Taos Amrouche and Mohand Bessaoud formed the Académie Berbère in Paris to encourage scholarly work on Amazigh society and support publishing infrastructure for Tamazight language literature. These activities would include the development of an alphabet system–Tifinagh–and the design of a flag, both of which are now critical instruments in contemporary Indigenous activism.[36] Inspired by these developments, Moroccan thinker and writer Ibrahim Akhiyyat founded a Rabat-based platform for Indigenous activism known as the Association marocaine pour de recherche et d’echange culturel (AMREC) in 1967. Note that at this time Indigenous activism was so controversial in Morocco that even dubbing it “Amazigh” in public forums was taboo.

Akhiyyat’s organization, drawing on the language of Marxist thinkers, advocated for a “profound cultural revolution” in Morocco, including educational and social policy that would center the Tamazight language as a key part of Moroccan identity.[37] He called for an Amazigh Renaissance (Nahda Amazighiyya); the use of the word nahda deliberately evoked the Arabic Nahda of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in which Pan-Arab nationalism had been formed through a growing print community of novelists, poetists, and scientists writing in a shared language of Standard Arabic. To that end, Indigenous activists began building a new vocabulary of words like ungal (novel) and amzgun (theater) to serve as the basis for a growing corpus of Amazigh literature.[38] “There’s no debate that there is a national intellectual revolution” focusing on popular culture and language in particular, wrote AMREC scholar Mohammad Moustaoui. “Our ignorance of popular literature is the result of our ignorance of parts of our own country.”[39] Yet the movement’s provocative calls for Indigenous rights, its questioning of Arab-Islamic identity, and its ties to the political left attracted the attention and repression of the state. When the Sorbonne-educated historian Ali Sidqi Azaykou published an article titled “Toward a Real Conceptualization of Our National Culture” criticizing Arabization policies, he was imprisoned, and the journal Amazigh: Revue marocaine d’histoire et de civilization shut down. From these experiences, Akhiyyat wrote, “we realized the enormity of the intellectual and ideological alienation affecting Moroccan minds and the extent of the country’s subservience to the Arab East culturally, artistically and politically.”[40] State repression of critical journals drove dissident politics into non-textual channels which could more easily escape the censor’s view. In listening to popular music from the past, historians can resurrect the voices of those marginalized from official narratives.

Ousmane: Modernizing Amazigh Music

Frustrated by the political limits on scholarly publications, and concerned with reaching a wider audience, in the early 1970s Akhiyyat and fellow activists Safi Moumin Ali and Ibrahim Mdran began recruiting members for an Amazigh musical band in the model of Nass el Ghiwane. They were perhaps also inspired by the success of the Algerian poet and folk singer Idir, whose 1976 Kabyle-language song “A Vava Inouva” had great commercial success. Akhiyyat recalled in his memoirs that AMREC’s popular music project was intended to be “a qualitative and revolutionary step in the field of Amazigh art.”[41] After several setbacks, including timid musicians who were worried they would be laughed off stage for singing in Tamazight and the theft of AMREC equipment by some hired session players, the lineup eventually settled on six musicians: lead singer and guitarist Mbarek Ammouri, guitarist Belaid Akkaf, organ player Tariq El Maaroufi, accordionist Al Yazid Kourfi, percussionist Said Boutroufin, and violinist Said Bejaad.[42] Most of them were immigrants from the Souss region of Southern Morocco whom Akhiyyat recruited when they were studying at universities in Rabat; he discovered Ammouri in the southern town of Taroudant playing a wedding in a fusion band called The Souss Five.[43] After honing their sound in a series of private performances in Rabat and Casablanca, the group settled on the name Ousmane, meaning “lightning” in Tamazight. They arrived on the Moroccan musical scene like a bolt of electricity.

As a musical venture organized and initially funded by AMREC, Ousmane was a political project with an explicit cultural message. The band, Akkaf writes in his 2022 memoirs, “was in service of the Amazigh cause and uprising (intifada) against the marginalization of Amazigh language and culture.”[44] The use of militant words like “revolution” and “intifada” reflected the artist-activists’ belief that music was inherently political. At the time, the poet Khaïr-Eddine favorably compared Ousmane to Indigenous activism in Europe aimed at reviving local languages like Breton and Welsh which “decrypt age-old secrets, updating them and making them usable today [...] Roughly the same thing is happening today in Morocco,” he wrote in Lamalif, “where Tamazight makes its way to the universities, while singers and musicians modernize the Shleuḥ register, bringing a breath of fresh air to a language that has seemed frozen and redundant. They voice not only a nostalgia for the lived past but also the construction of the always critical and improbable future. They are, in a sense, the poets of the Berber renaissance.”[45] Both the band and their intellectual allies viewed music as a key weapon in the arsenal of activists attempting to make Indigenous culture visible and audible for Moroccan audiences. In listening to their music, we can hear the frustrated aspirations of a generation searching for new ways to represent itself within the national community.

In building this nostalgic sound and delivering it to a receptive Indigenous audience in both North Africa and Europe, Ousmane and AMREC tapped into the enormous musical energies unleashed by Nass el Ghiwane’s success. Ousmane published music on the same label, Boussiphone, that had originally built a distribution network across Europe and North Africa based on the strength of Ghiwani record sales.[46] The band played on the same stages, like the Mohammed V Theatre in Rabat and the Royal Cinema in Casablanca, which Nass el Ghiwane had regularly filled to capacity with their trance-inducing folk music. Indeed, Ousmane’s first tour of Europe in 1977 was conducted alongside Nass el Ghiwane, who the year before had been the first North African band to be invited to play the legendary L’Olympia Theatre.[47] At around the same time, Omar Sayed produced some of the first records of Izenzaren, another Amazigh band that formed shortly after Ousmane but performed songs closer in style to Ghiwani folk music.[48] Similar experiments were happening in the Rif, where leftist student activism and Ghiwani rhythms produced Tarifit language bands like Tawattun in the late 1970s.[49] Other groups soon followed across Morocco, including Archach, Tawada, Aytmatn, and others, in a Tamazight language sub-genre of Dhahira music sometimes called Tagroupit. Experimenting with a wide variety of sounds and styles, these artists built an exciting musical scene in the otherwise repressive cultural atmosphere of 1970s Morocco.

For Akhiyyat and the members of Ousmane, modernity was a key element of Amazigh activism. With their instruments and in their melodies and lyrics, the band rejected the folklore label thathad so often been applied to Amazigh art and embraced rational, scientific bases for musical production. Whereas Nass el Ghiwane had grounded their musical practice in “heritage research,” Ousmane was guided by an artistic philosophy of “development” (taṭwīr) and “renewal” (tajdīd). The band liked to stress in press interviews that their members had been classically trained at the National Conservatory and were conversant in Western solfege theory and musical notation.[50] Ammouri once told an interviewer that “we must not only preserve the cutting edge of our songs, but also in a certain sense put a foot in the future.”[51] Ousmane were “scientists as much as they were militants,” wrote one French observer. They wanted to “transform traditional music. Not to shake it apart but, from its village bases and influences, make it cool and dapper, even for a non-Berber ear.”[52] This modernist bent was reflected in the band’s choice of electric instruments like the organ, as opposed to the local North African instruments then in vogue among Ghiwani bands. Their fusion used Western tools like the vinyl record and the electric guitar to reject folklorism as a colonial concept which had no bearing on contemporary Moroccan culture. Ousmane, one journalist wrote in 1976, “rises against the notion of folklore which, they tell us, enters with the imperialist strategy and was merely an excuse of Western cultural colonialism to take charge.”[53]

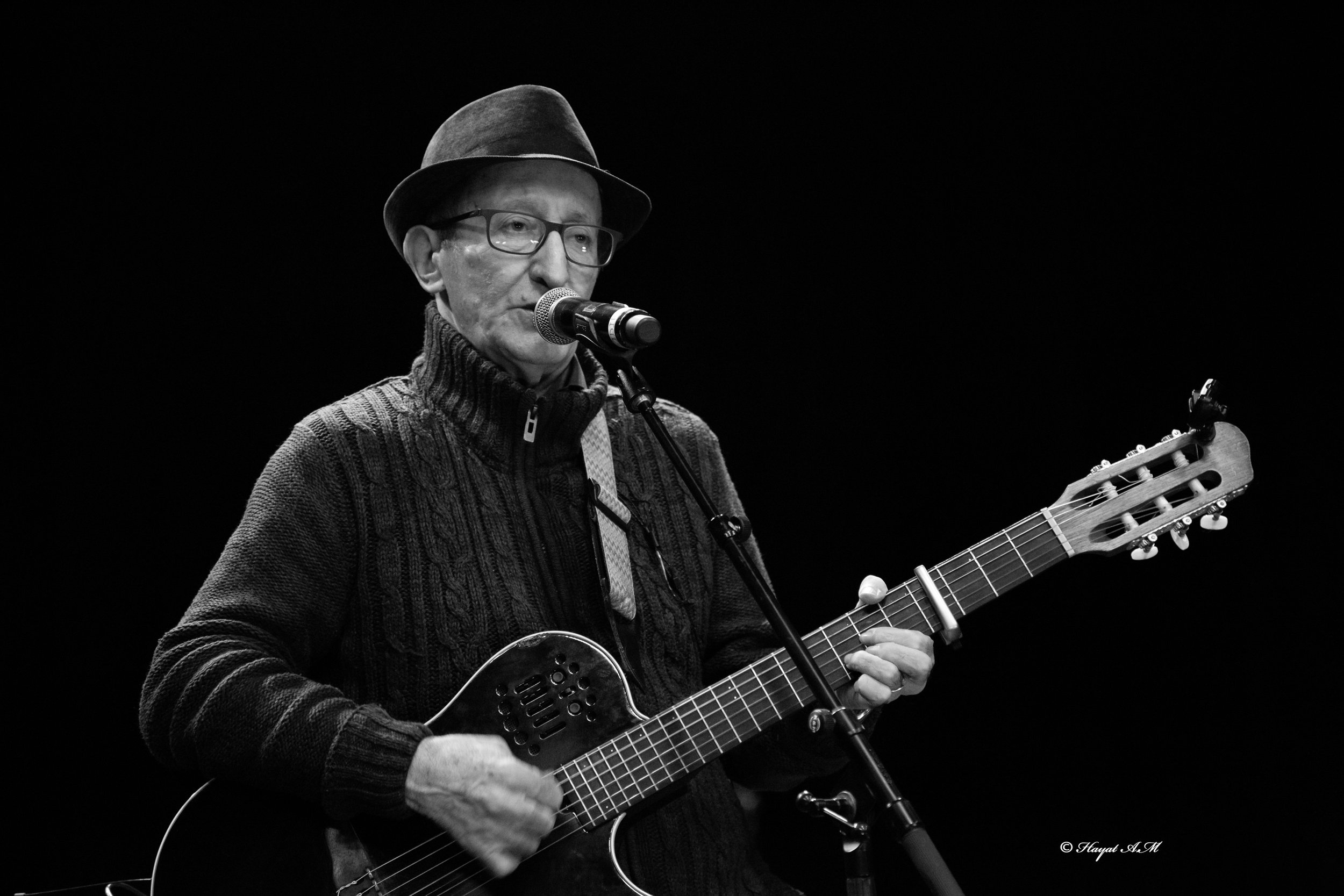

FIG. 1. Ousmane, 1976. Muhammad Nabzi, “Ousmane: ḥarakah jādah li-taṭwīr al-ughniyah al-amazighiyah” Al-Muharrir, 2 June 1976.

Beyond merely rejecting colonial constructions of Moroccan culture, Ousmane followed in the footsteps of Nass el Ghiwane by writing politically-tinged songs of refusal and dissent. With song titles like “Takendout” (Hypocrisy), “Tillas” (Darkness), and “Tabrrat” (The Message), Ousmane denounced political repression and the marginalization of rural communities. Most of their work originated from “the reality of society” wrote one commentator.[54] “We have no sentimental songs, properly speaking,” Ammouri told one interviewer. “The themes of our songs are for the most part social, mixed with description of the people and the land of southern Morocco.”[55] This mixture evoked the beauty and nostalgia of rural Morocco while also speaking to the “social” issues that affected urban audiences, like unemployment and injustice.

Ousmane’s brand of Amazigh modernism laid claim to a historical authenticity even as it strove to present new music to modern audiences. Although they sang mostly in the Soussi dialect of Tamazight, the band made a conscious effort to compose songs in Amazigh dialects from across Morocco, “not to encourage regionalism, but to contribute to a cultural fusion. They want their arrangements to sound modern and therefore transcending place rather than merely native.”[56] In addition to composing original songs, they also repurposed many traditional poems from the Rrways tradition of Southern Morocco, citing Boubaker Anchad, Hadj Belaid, and Sidi Hammou Outaleb among others as important influences. In the words of Akkaf, the band “performed these songs in a modern template which took care to guard its authenticity while still providing scientific musical arrangements following techniques known worldwide. All for the sake of bringing the new generations closer to this ancient heritage.”[57] Although employing different methods and vocabulary, the band shared with Nass el Ghiwane an interest in connecting postcolonial audiences with precolonial heritage.

Ousmane’s valorization of Amazigh art and heritage was not without its controversies. The militant musicians’ proud presentation of Indigenous language and culture on Morocco’s public stages generated a fierce backlash from the Arabophone establishment. Ousmane’s first two recordings, “Tillas” and “Takendout” enjoyed great popularity on French airwaves and on the French-language channels in Morocco, but Morocco’s Arabic-language programs reportedly refused to play the singles.[58] As tensions rose, the Amazigh public that was coalescing around Ousmane reacted strongly. At a March 1977 concert at the Mohammed V Theater in Rabat, Ousmane fans booed an emcee off the stage for attempting to address the crowd in Arabic.[59] Some critics in the press began pitting Dhahira bands against Ousmane, suggesting that the latter’s refusal to sing in Arabic showed a lack of patriotism. This led AMREC writer Mohamed Moustaoui to denounce the “dangerous press battle” between Nass el Ghiwane and Ousmane and called for an end to the “rocket revolution,” saying that “our shared goal is to give freedom to the tongue.”[60] Most provocatively, one writer in the magazine Al Fan likened the rise of Amazigh popular music to “a new Berber Dahir.” “Since the appearance of Ousman [sic], the Chleuh have been resurgent, taking pride in their origins. These musicians only speak Berber or French and would like to preserve their language and their customs in isolation. Is this the truth?” the writer asked angrily. “It is important to know because such an attitude would be the catalyst for great threats to the unity of the country.”[61] These anxieties around Indigenous activism and the growing visibility of Amazigh culture reflected the endurance of the colonial divide and rule policies as well as the deep ambivalences at the heart of postcolonial Moroccan nationalism.

“Dounit:” The World on a Record

“Dounit” was Ousmane’s second single, recorded live during their famous 1977 performances at L’Olympia in Paris. The B side, incorrectly labeled “Dounit” as well, is in fact the song “Asmammi” (Complaint), also recorded at the same concert. This 7” record was issued on the Milodisk imprint of Boussiphone Records, one of the largest and most prolific Moroccan record labels of the 1970s. The label’s founder, Abderrahim Boussif, created Morocco’s first record pressing plant in 1967, eventually establishing a network of family-run stores spread across Casablanca, Paris, and Brussels. The stores produced vinyl records,cassette tapes, and eventually VHS movies.[62] Frustrated by the dominance of Egyptian and Lebanese artists in the 1960s, Boussif deliberately platformed an array of North African styles in his record catalog, including Mauritanian desert rock, Algerian Rai, and Ghiwani folk music. The catalog number of “Dounit,” MB 2404, indicates its position in the label’s Amazigh collection among other artists like Izenzaren, Izenkad, and Benasser Oukhouya.

The turntable is a key to the record’s subdued visual appearance, unlocking the grooves etched into its surface and resurrecting the youthful voices of the transnational ACM. Ammouri’s voice rises above the hubbub of the crowd at L’Olympia to deliver the lyrics of “Dounit” a capella:

“O world, you are a big mountain to me

A holy ramp apt to weary the traveler

O world, you are a big mountain to me

We approach you as a camel would

Insinuating that we wish to bend the knee

O world, you are a big mountain to me

I don't trust this life or anyone in it

An act of charity will only bring regret

O world, you are a big mountain to me”[63]

Immediately after finishing this melancholic verse, the percussion section starts in a quick triplet time signature. The recording captures the roar of the crowd as the rest of the band joins in with a bluesy, organ-driven groove accompanied by flourishes of the violin and guitar. Ammouri repeats the verses of the poem, with the band joining him after each chorus to lament in unison: “O world, o world, o world.” The recording brings Ousmane’s conception of Amazigh modernity to life, bemoaning the weight of the modern world in the form of a “big mountain” crushing Indigenous communities even as the pace of the song gradually quickens, propelling the band and the audience forward together into the future. At the end of the song, the instruments abruptly cut out as the drums launch into a percussion solo which whips the crowd into a frenzy of whooping and clapping reminiscent of the crescendos of chaabi music. The 7” recording still transmits the joy that the audience of young Maghrebi immigrants felt that night in the Paris of February 1977 as they danced to the beat of modern Amazigh music, celebrating the survival of Indigenous culture even as they mourned the losses inflicted by colonial exploitation and postcolonial nationalism.

Amazigh Representation in Contemporary Morocco

Ousmane’s spark burned brightly but briefly. After just four years together, the group went on hiatus in 1978. After a handful of reunion concerts over the following years, they announced a permanent end to the band in 1984. In the repressive political climate of the Years of Lead, rumors spread that they had been forced underground by the state. The band in later years has denied these rumors, distancing themselves from political activism by claiming that “some of our songs had a political appearance, but despite that we never intended to take a controversial tone.”[64] The band members have been notoriously tight-lipped, but it seems likely that, like many of their Western contemporaries, the young men split due to personal and artistic differences. Mbarek Ammouri went on to a have a successful solo career, singing some songs composed by the imprisoned Amazigh activist Azaykou and earning the nickname “the Moroccan Bob Dylan,”[65] while in the ‘80s Belaid Akkaf and Tariq El Maaroufi performed for a few years under the moniker Ousmane 2.

Nonetheless, the band’s championing of Amazigh language and culture on the biggest stages in North Africa and France contributed to a revolution in Indigenous representation. The early Amazigh activism of the 1960s and ‘70s, intensified by the so-called 1980 “Berber Spring” in Algeria, succeeded in gaining official recognition for Indigenous people and legal status for local languages. In 2001, a state-funded Royal Institute for Amazigh Culture (IRCAM) was established and after the 2011 protests Morocco’s new constitution made Tamazight an official language alongside Arabic. In the realm of popular discourse, some of today’s most popular Moroccan musicians like DJ Hamida and L’Artiste proudly claim Amazigh identity. Whereas in the early 1970s Akhiyyat had struggled to find musicians willing to sing Tamazight in public, today a new generation of artists enthusiastically displays symbols of Amazighité like facial tattoos and local textile designs in their music videos and album covers.[66] Following in the steps of Ousmane, these contemporary artists borrow freely from both North Africa and Europe. They sing in a mixture of Tamazight, Arabic, French, and English while incorporating new instruments and genres like hip hop and electronic music, presenting a linguistically and culturally hybrid vision of North African identity which was not possible in the politically repressive, anti-Indigenous atmosphere of post-colonial Morocco before Ousmane arrived.

However, the story of musicians’ struggle against state repression is not yet over. With the death of Hassan II in 1999 and the succession of his son Mohammed VI as king, the state has sought to project an image of greater political and cultural openness. Key to this strategy have been new folkloric framings of Amazigh, Sufi, Jewish, and African cultural heritage, which Hisham Aidi has characterized as new “sources of soft power” in the Moroccan regime’s toolkit.[67] In state-sponsored venues like IRCAM and the annual Timitar music festival, Berber dance and music are “cast as unchanging, [turning] these cultural forms into something exotic, folklore to be consumed by foreign tourists and more ‘modern’ Moroccan citizens.” In these official discourses, Aomar Boum argues, Berbers are configured “not as people with historical grievances against the state, but as people with striking dance steps, attractive clothes and jewelry, and beautiful casbahs.”[68] Rural Indigenous communities in the Atlas Mountains and the Sahara desert, meanwhile, remain some of the poorest and most under-resourced in all of Morocco. The state has folklorized Amazigh people and culture in exactly the ways Ousmane protested in the 1970s. As a new generation of artists emerges to reinterpret Indigenous music, the struggle continues to define Moroccan identity for today’s listeners.

Bibliography:

Archival Sources Accessed at the National Library, Rabat, Morocco

Al Alam

Al Funūn

Al Muharrir

L’Opinion

Published Sources

Abu-Lughod, Janet. Rabat: Urban Apartheid in Morocco. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Akhiyyat, Ibraham. al-Nahḍah al-Amāzīghīyah kamā ʻishtu mīlādahā wa-taṭawurahā. Rabat: AMREC.

Akkaf, Belaid. Majmūʿat Ūsmān al-asṭūrah. Casablanca: Editions La Croisée des Chemins, 2022.

Aidi, Hisham. “National Identity in the Afro-Arab Periphery: Ethnicity, Indigeneity and (anti)Racism in Morocco” Africa and the Middle East: Beyond the Divides POMEPS 40, June 2020: 66.

Bahassou, Réda. Nass el Ghiwane: Hérauts de la musique contestataire. Casablanca: Editions La Croisée des Chemins, 2021.

Batma, Larbi. Al-Rahil: Sira dhātiyya. Casablanca: Al-Rabita Company, 1995.

Boum, Aomar. “Festivalizing Dissent in Morocco,” Middle East Report, no. 263 (2012): 23.

Burke III, Edmund. “The image of the Moroccan state in French ethnographic literature: a new look at the origin of Lyautey’s Berber policy” in Arabs and Berbers eds. Ernest Gellner and Charles Micaud. Massachusetts: Lexington Books, 1972.

El Guabli, Brahim. Moroccan Other Archives: History and Citizenship After State Violence. New York: Fordham University Press, 2023.

El Guabli, Brahim. “Literature and Indigeneity: Amazigh Activists’ Construction of an Emerging Literary Field” 28 October 2022, Los Angeles Review of Books.

El Guabli, Brahim. “Translation and Indigeneity—Amazigh Culture from Treason to Revitalization” The Markaz Review, 14 August 2023. https://themarkaz.org/translation-and-indigeneity-amazigh-culture-from-treason-to-revitalization/

El Guabli, Brahim and Ali Alalou. Lamalif : A Critical Anthology of Societal Debates in Morocco during the “Years of Lead” (1966-1988) Volume 1. (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2022).

Ennaji, Moha. Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco. New York, NY: Springer US, 2005.

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Trans. Richard Philcox. New York: Grove Press, 2004.

Fahmy, Ziad. Street Sounds: Listening to Everyday Life in Modern Egypt. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2020.

Fernandez Parilla, Gonzalo. “The Challenge of Moroccan Cultural Journals of the 1960s” Journal of Arabic Literature, 2014, Vol. 45, No. 1 (2014): 128.

Gilson Miller, Susan. A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Glasser, Jonathan. The Lost Paradise: Andalusi Music in Urban North Africa. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Harrison, Olivia and Teresa Villa-Ignacio, editors. Souffles-Anfas : A Critical Anthology from the Moroccan Journal of Culture and Politics. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2016.

“Interview with Abderrahim Boussif in Brussels” Boussiphone 7 April 2017, https://boussiphone.wordpress.com/blog/.

Irbouh, Hamid. Art in the Service of Colonialism: French Art Education in Morocco, 1912-1956. London: Tauris Academic Studies, 2005.

Lefébure, Claude. “Ousman: La Chanson Berbère Reverdie” Nouveaux enjeux culturels au Maghreb, (Paris: CNRS, 1982): 189-208.

Levine, Mark. Heavy Metal Islam: Rock, Resistance, and the Struggle for the Soul of Islam. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2008.

Maghraoui, Driss. “Introduction” in Revisiting the Colonial Past in Morocco. Abingdon: Routledge, 2013.

Maddy-Weitzman, Bruce. The Berber Identity Movement and the Challenge to North African States. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011.

Miller, Susan Gilson. History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

“Morocco: Lift Restrictions on Amazigh (Berber) Names” Human Rights Watch, 3 September 2009.

Oudaden, Hassane. “Rwāys and Tirruyssā: A Symbolic Site of Amazigh Identity and Memory” Jadaliyya, 1 November 2021 https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/43446/Rw%C4%81ys-and-Tirruyss%C4%81-A-Symbolic-Site-of-Amazigh-Identity-and-Memory

Pasler, Jann. “The Racial and Colonial Implications of Music Ethnographies in the French Empire, 1860s–1930s” in Critical Music Historiography: Probing Canons, Ideologies and Institutions, eds. Vesa Kurkela and Markus Mantere. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing, 2015.

Silver, Christopher. Recording History: Jews, Muslims, and Music Across Twentieth Century North Africa. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2022.

Silver, Christopher. “The Sounds of Nationalism: Music, Moroccanism and the Making of Samy Elmaghribi.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 52, no. 1 (February 2020): 42.

Stafford, Andy. “‘Writing is an act, the poem is a weapon and the discussion an assembly:’ The Political Turn in Souffles during Morocco’s 1968” Forum for Modern Language Studies Vol. 59, No. 3, 23 September 2023.

Swedenburg, Ted. “On the Origins of Pop Rai.” Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication 12, no. 1 (2019): 7–34.

Tolan-Szkilnik, Paraska. Maghreb Noir: The Militant-Artists of North Africa and the Struggle for a Pan-African, Postcolonial Future. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2023.

Touaf, Larbi. "The sense and non-sense of cultural identity in Mohammed Khair-Eddine's fiction." Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, no. 32, annual 2012.

Vogl, Mary. “Art Journals in Morocco: New Ways of Seeing and Saying” The Journal of North African Studies, 21:2, 240.

Wyrtzen, Jonathan. Making Morocco: Colonial Intervention and the Politics of Identity. Ithaca, United States: Cornell University Press, 2016.

Footnotes

[1] “Les Ousmane ont dignement marqué leur passage en France” L’Opinion, 17 February 1977.

[2] Mounir Rahmouni, “Rencontre avec le groupe de musique berbère Ousmane” L’Opinion, 3 March, 1977.

[3] Susan Gilson Miller, A History of Modern Morocco (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 2-3.

[4] Driss Maghraoui, “Introduction” in Revisiting the Colonial Past in Morocco, (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013).

[5] Ziad Fahmy, Street Sounds: Listening to Everyday Life in Modern Egypt (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2020).

[6] Mark Levine paraphrasing Philip Bohlman in Heavy Metal Islam: Rock, Resistance, and the Struggle for the Soul of Islam (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2008): 4.

[7] Christopher Silver, Recording History: Jews, Muslims, and Music Across Twentieth Century North Africa (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2022): 15.

[8] Brahim El Guabli, Moroccan Other Archives: History and Citizenship After State Violence (New York: Fordham University Press, 2023): 14.

[9]Ibid, 54.

[10] Edmund Burke III “The image of the Moroccan state in French ethnographic literature: a new look at the origin of Lyautey’s Berber policy” in Arabs and Berbers eds. Ernest Gellner and Charles Micaud (Massachusetts: Lexington Books, 1972): 175.

[11] Graduates of the Collège included the future Amazigh writer and activist Mohamed Chafik. Spencer Segalla. The Moroccan Soul: French Education, Colonial Ethnology, and Muslim Resistance, 1912-1956 (University of Nebraska Press, 2009): 141.

[12] Irbouh, Hamid. Art in the Service of Colonialism: French Art Education in Morocco, 1912-1956 (London: Tauris Academic Studies, 2005).

[13] Guillot de Saix quoted in Jonathan Glasser, The Lost Paradise: Andalusi Music in Urban North Africa (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2016): 211-212.

[14] Jann Pasler “The Racial and Colonial Implications of Music Ethnographies in the French Empire, 1860s–1930s” in Critical Music Historiography: Probing Canons, Ideologies and Institutions, eds. Vesa Kurkela and Markus Mantere (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing, 2015): 17–45.

[15] Jonathan Wyrtzen, Making Morocco: Colonial Intervention and the Politics of Identity (Ithaca, United States: Cornell University Press, 2016): 177.

[16] Miller, History of Modern Morocco, 126 - 129.

[17] Wyrtzen, Making Morocco, 284.

[18] Moha Ennaji Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco (New York, NY: Springer US, 2005).

[19] Brahim El Guabli, “Translation and Indigeneity—Amazigh Culture from Treason to Revitalization” The Markaz Review, 14 August 2023 https://themarkaz.org/translation-and-indigeneity-amazigh-culture-from-treason-to-revitalization/

[20] Maddy-Weitzman, The Berber Identity Movement: 89.

[21] This practice continued as late as 2009 “Morocco: Lift Restrictions on Amazigh (Berber) Names” Human Rights Watch, 3 September 2009.

[22] In the 1970s and 80s the Indigenous artist Mohamed Albensir, a singer in the rwāys tradition of Southern Morocco, lamented in his songs that “The value of the Amazigh language has fallen/ Those who have value are Farid, Kelthoum, and Abdelwahab/ Abdelhalim has just been rewarded hasn’t he?” translated in Hassane Oudaden, “Rwāys and Tirruyssā: A Symbolic Site of Amazigh Identity and Memory” Jadaliyya, 1 November 2021 https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/43446/Rw%C4%81ys-and-Tirruyss%C4%81-A-Symbolic-Site-of-Amazigh-Identity-and-Memory

[23] Christopher Silver, “The Sounds of Nationalism: Music, Moroccanism and the Making of Samy Elmaghribi.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 52, no. 1 (February 2020): 42.

[24] Gonzalo Fernandez Parilla, “The Challenge of Moroccan Cultural Journals of the 1960s” Journal of Arabic Literature, 2014, Vol. 45, No. 1 (2014): 128.

[25] Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 2004): 174. Fanon was the second-most cited writer in the pages of Souffles, after only Marx himself, Paraska Tolan-Szkilnik Maghreb Noir: The Militant-Artists of North Africa and the Struggle for a Pan-African, Postcolonial Future (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2023): 45.

[26] Abdellatif Laábi “Realities and Dilemmas of National Culture” in Souffles-Anfas : A Critical Anthology from the Moroccan Journal of Culture and Politics, edited by Olivia C. Harrison, and Teresa

Villa-Ignacio, Stanford University Press, 2015.

[27] Ibid.

[28] He added “Now that we are faced with great problems of nation-building, the question of literature must be asked plainly and frankly: in countries that are largely illiterate, that is to say where the written word has very little chance of transforming things, can we liberate a people using a language it does not understand?” Zakya Daoud, “Abdelkébir Khatibi: We Must Attempt a Lasting Double Critique” trans. Matthew Reeck, in Lamalif: A Critical Anthology of Societal Debates in Morocco during the “Years of Lead" (1966–1988): Volume 1, edited by Brahim El Guabli and Ali Alalou, 267–74. Liverpool University Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv32nxxb6.46.

[29] Ahmed Bouanani “Introduction to Popular Moroccan Poetry” trans. Robyn Creswell, in Souffles-Anfas : A Critical Anthology from the Moroccan Journal of Culture and Politics, edited by Olivia C. Harrison, and Teresa Villa-Ignacio, Stanford University Press, 2015.

[30] Larbi Touaf "The sense and non-sense of cultural identity in Mohammed Khair-Eddine's fiction." Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, no. 32, 2012.

[31] For more on colonial land policies, see Janet Abu-Lughod. Rabat: Urban Apartheid in Morocco. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014).

[32] “ؤadha qadamat al-mujamūʿāt al-ghināʾiyyah li-ṭifāl Lubnān” Al Alam, 26 September 1976.

[33] Larbi Batma, Al-Rahil: Sira dhātiyya (Casablanca: Al-Rabita Company, 1995).

[34] “Hal hiya ẓāhirah am mawjah?” al-Funūn, January - March, 1975.

[35] Larbi said of “Arraghaya” and the music of the Zayan region: “the goal of this research is foremost to put the listener in the ambiance of the Middle Atlas but with lyrics explicitly in Arabic dialect. The Ghiwani movement lives the authenticity which we must search for in the reality of our society, in the everyday lives of the people. This music is a new tool of heritage research” Omar Annouari, “Entretien: Larbi Batma” L’Opinion, 1 March 1980.

[36] Maddy-Weitzman, Berber Identity Movement.

[37] El Guabli, Moroccan Other Archives: 29.

[38] Brahim El Guabli, “Literature and Indigeneity: Amazigh Activists’ Construction of an Emerging Literary Field” 28 October 2022, Los Angeles Review of Books.

[39] Mohammad Moustaoui, “Min shiʿr al-rawāyis ilá majmūʿat Ūsmān: al-ḥaqīqah al-asṭūrah” Al Alam, Feb 1977.

[40] Ibraham Akhiyyat, al-Nahḍah al-Amāzīghīyah kamā ʻishtu mīlādahā wa-taṭawurahā (Rabat: AMREC): 78.

[41] Ibid, 77.

[42] Belaid Akkaf, Majmūʿat Ūsmān al-asṭūrah (Casablanca: Editions La Croisée des Chemins, 2022): 18-19.

[43] Akhiyyat, al-Nahḍah al-Amāzīghīyah: 79.

[44] Akkaf, Ousmane: 23.

[45] Mohammed Khair-Eddine “Rediscovering the South” trans. Khalid Lyamlahy in Lamalif : A Critical Anthology of Societal Debates in Morocco during the “Years of Lead” (1966-1988) Volume 1, eds. Brahim el Guabli and Ali Alalou (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2022): 93-94.

[46] “Interview with Abderrahim Boussif in Brussels” Boussiphone 7 April 2017, https://boussiphone.wordpress.com/blog/

[47] The band was accused of creating a “kind of social delirium” at that concert, in which young Maghrebi immigrants shook the stands and fell into trances. “Nass el Ghiwane wa al-farḥ al-maghribi ʿalā khushubat L’Olympia” Al-Alam, 9 May 1976.

[48] Réda Bahassou, Nass el Ghiwane: Hérauts de la musique contestataire (Casablanca: Editions La Croisée des Chemins, 2021): 120-124.

[49] Mohamed Oubenal “Amazigh Protest Music of the Rif Region” trans. Ben Connor, Souffles Monde no. 1, 2023.

[50] Muhammad Nabzi, “Ousmane: ḥarakah jādah li-taṭwīr al-ughniyah al-amazighiyah” Al-Muharir, 2 June 1976.

[51] Abdallah Bensmain, “Ousmane: Une lumière dans l’obscurité” L’Opinion, 7 Oct 1976.

[52] Claude Lefébure, “Ousman: La Chanson Berbère Reverdie” Nouveaux enjeux culturels au Maghreb, (Paris:CNRS, 1982): 189-208.

[53] Bensmain, “Une lumière dans l’obscurité” L’Opinion, 7 Oct 1976.

[54] Muhammad Nabzi, “Ousmane: ḥarakah jādah li-taṭwīr al-ughniyah al-amazighiyah” Al-Muharir, 2 June 1976.

[55] Bensmain, “Ousmane: Une lumière dans l’obscurité” L’Opinion, 7 Oct 1976.

[56] Lefébure, “Ousman: La Chanson Berbère Reverdie:” 195.

[57] Akkaf, Ousmane: 158.

[58] Mounir Rahmouni, “Echoes” L’Opinion, 27 May 1976.

[59] “Some of the politicians in attendance never imagined that public voices would rise with that force to declare that they were not Arab” writes Akhiyyat in al-Nahḍah al-Amāzīghīyah: 77.

[60] Mohamed Moustaoui, “Mu’arikah ṣaḥafiyyah khatīrah bayn Nass el Ghiwane wa Ousmane” Al-Adala, 29 October 1976.

[61] Author unnamed, quoted in Lefébure, “Ousman: La Chanson Berbère Reverdie:” 202.

[62] “Interview with Abderrahim Boussif in Brussels” Boussiphone 7 April 2017, https://boussiphone.wordpress.com/blog/

[63] My thanks to Soufian Amzile for help with the translation.

[64] Akkaf, Ousmane: 27.

[65] Bahassou, Nass el Ghiwane: 128.

[66] See some fun recent examples from Manal, Nayra, and DJ Hamida.

[67] Hisham Aidi “National Identity in the Afro-Arab Periphery: Ethnicity, Indigeneity and (anti)Racism in Morocco” Africa and the Middle East: Beyond the Divides POMEPS 40, June 2020: 66.

[68] Aomar Boum, “Festivalizing Dissent in Morocco,” Middle East Report, no. 263 (2012): 23.

How to Cite:

Jones, B., (2024) “Recording Lightning: Popular Music and the Amazigh Cultural Movement”, Tamazgha Studies Journal 2(1), 8-25.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 2 • Issue 1 • Spring 2024

Pages 8-25

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Georgetown University

Keywords: band Ousmane; Morocco; Morocco; Amazigh music; Years of Lead.