Introduction

AUTHOR: Nabil Boudraa, Karim Ouaras

INTRODUCTION

Nabil Boudraa

Oregon State University

Karim Ouaras

University of Oran 2/ Centre d’Études Maghrébines en Algérie

Introduction

In the realm of music, there are certain artists whose voices transcend generations, cultures, and borders, leaving an indelible mark on the world. One such artist is the beloved Kabyle singer, Idir. With his soul-stirring melodies and profound lyrics, Idir captivated hearts around the globe, becoming a symbol of resilience, cultural identity, and unity.

In this journal volume, we have curated a collection of scholarly articles, personal reflections, and interviews that delve deep into the multifaceted legacy of Idir. Through these contributions, we explore the artistic genius of Idir, his role as a cultural ambassador, and the profound influence he had on the Kabyle music landscape. We also examine the socio-cultural context in which his music emerged, shedding light on the historical, linguistic, and political dimensions that shaped his artistic career.

Each article within this volume offers a unique perspective on Idir’s life and music, presenting a comprehensive and holistic understanding of his enduring impact. From his humble beginnings in the Kabylia region of Algeria to his ascent as a global musical icon, Idir’s artistry has resonated deeply with audiences, reaching far beyond the borders of Kabylia and those of Algeria, in general. More importantly, we, the editors, feel honored to include our interview with the celebrated Kabyle poet-singer, Lounis Aït Menguellet, who shares not only insights on Idir’s musical repertoire, but also on his decades-long friendship with Idir himself.

Throughout his career, Idir consistently championed the preservation and celebration of Kabyle culture, language, and heritage. His music beautifully intertwined traditional Kabyle folk sounds with contemporary influences, creating a harmonious blend that touched the souls of millions. His songs conveyed profound emotions, telling stories of love, longing, hope, and the human experience, while also shedding light on the social and political challenges faced by the Kabyles (and the Amazigh people, in general). For them, Idir is a symbol of their Berber culture and one of the heroes who never stopped defending their culture and identity, even from exile. The famed French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who completed most of his sociological fieldwork in the Algerian region of Kabylia, has once said that, “He [Idir] is not a singer like the others. He is a member of each family.” It must be noted that Idir was doing this great work when the regime did not even allow Kabyle language to be spoken in public spaces. Kabyle activists and cultural icons were even imprisoned for simply resisting these exclusion and shaming policies and practices. His song Izumal, for example, is dedicated entirely to this issue.

Idir’s impact extended beyond the realm of music. As an advocate for cultural diversity and peace, he used his platform to promote dialogue, understanding, and unity among different communities. He believed in the power of music as a universal language that could bridge divides and foster connections, inspiring generations to embrace their roots and one another. His album Identités is a perfect illustration of his unifying force.

Biographical Context

Idir was born as Hamid Cheriet on October 25, 1949, in the small Kabyle village of At Lahcène, near Tizi Ouzou, Algeria. From a young age, he demonstrated a deep passion for music, drawing inspiration from his Kabyle roots and the vibrant musical traditions of the region. With his velvety voice and remarkable guitar skills, Idir breathed new life into traditional Kabyle melodies, infusing them with contemporary elements to create a unique blend that resonated with audiences far and wide.

In the colonial and postcolonial contexts many Kabyle singers such as Slimane Azem, Cheikh El Hasnaoui, Zerrouki Allaoua, Cherif Kheddam, Lounis Ait Menguellet, Lounès Matoub, Ferhat Imazighen Imoula, Cherifa, Nouara, Djamel Allem, Idheflawene, Thagrawla, Abranis, and, of course, Idir used their music and lyrics to revitalize cultural heritage, to resist oppression and violence, and to advocate for the rights of the Amazigh people. By voicing their discontent, these singers provided opportunities and platforms for marginalized voices to be heard and raised awareness among them. In that regard, Kabyle music helped uncover and save Amazigh history and cultural roots from oblivion.

Based on oral traditional literature and its powerful symbolic narratives, Kabyle music is known for using traditional instruments such as the mandolin, the flute, ajouaq, ghaita, t’bel, and the bendir.[1] Its lyrics often address themes of love, social issues, exile, the conditions of women, freedom, and the struggles of the Amazigh people over time. Holding poetry in high esteem, Kabyle (and Amazigh) women have been key guardians of achewiq,[2] North Africa’s oldest music genre, through which they ensured the continuity of Amazigh cultural heritage from time immemorial. Nowadays, Kabyle singers continue to use tales, social imaginaries, and traditional instruments to irrigate their contemporary creative compositions.

In the mid 1970s, Idir burst onto the international music scene with his timeless debut album, “A Vava Inou va,” which quickly became a global sensation. This groundbreaking album, featuring the eponymous hit single, showcased Idir’s exceptional ability to merge tradition and modernity, captivating listeners with his soulful renditions and poetic lyrics. The success of “A Vava Inou va” propelled Idir to international acclaim, solidifying his place as one of the most influential Kabyle musicians of all time.

Throughout his illustrious career, Idir released numerous albums, each a testament to his artistic brilliance and unwavering commitment to his cultural heritage. He collaborated with renowned musicians from around the world, fostering cross-cultural exchanges and promoting the beauty of Kabyle music beyond the shores of North Africa. Idir’s music became a beacon of hope, a call for unity, and a celebration of Kabyle identity, resonating with diaspora communities and music enthusiasts globally.

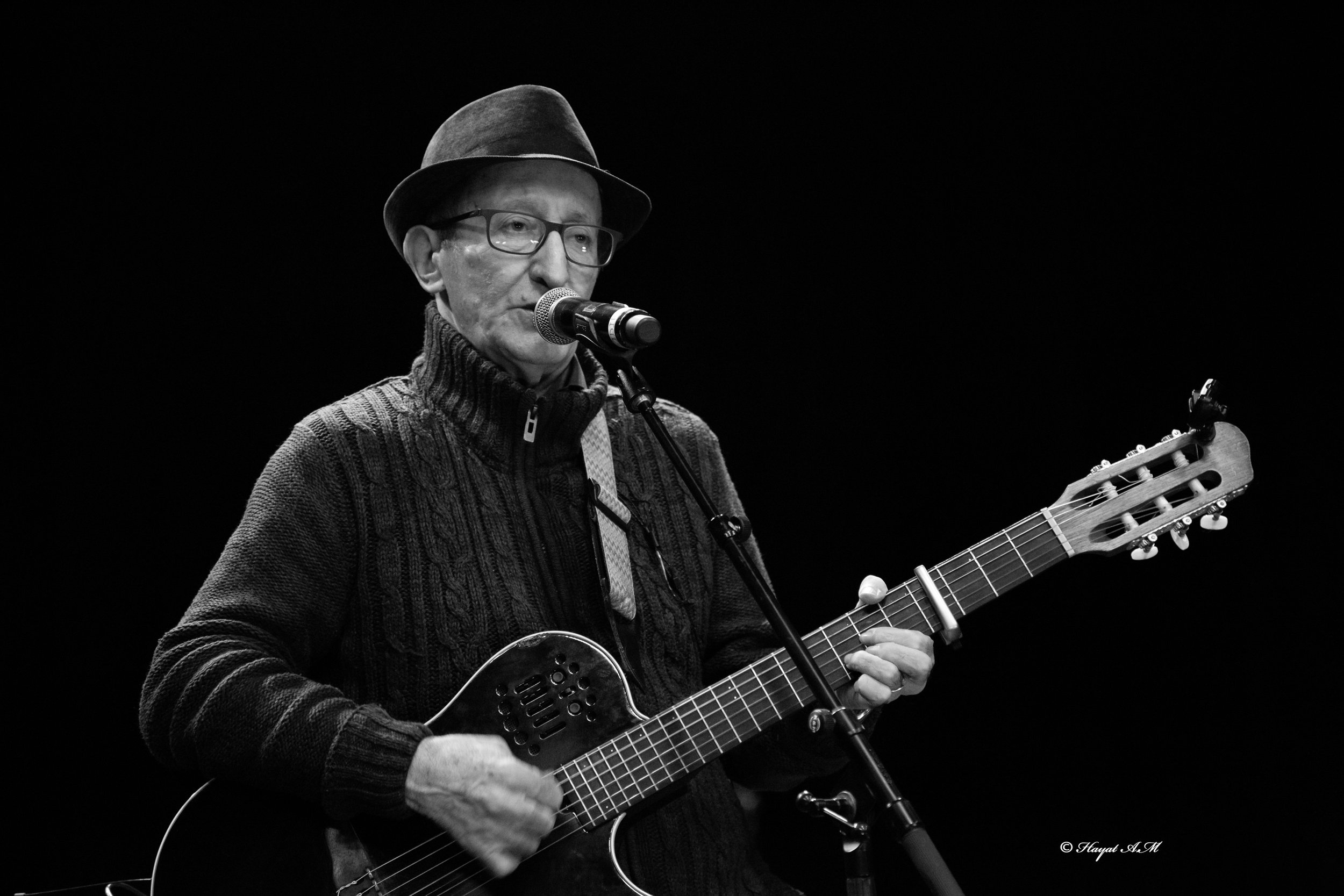

FIG. 1. Idir. Credit: Hayat Aït Menguellet.

Geopolitical context:

Idir was a product of his time, but also of his native Kabylia, known as an ever-lasting stronghold of resistance. To better understand Idir, one has to have some relative knowledge about his homeland, Kabylia. During French colonial rule, Kabylia (the Berber region of Algeria) was a site of repeated resistance—including Fadhma N’Soumer’s rebellion against early occupation in 1857, the insurrection led by Shaykh El Mokrani and Shaykh Belhaddad of the Rahmaniyya Sufi brotherhood in 1871, the FLN’s organizational Soummam Congress in 1956 and Colonel Amirouche’s military campaigns during the war of national liberation from 1954–1959. Immediately following independence in 1962, Hocine Aït Ahmed, one of the local heroes of the revolution, took up arms against the FLN’s single-party tyranny. The uprising was crushed, and successive FLN governments pursued Arabization policies, repressed the Berber language (Tamazight) and cultural rights, and economically and politically controlled Kabylia for the next 40 years, even as individuals from the region did achieve some measure of educational and professional success and sometimes high positions within the state administration.

Kabyles continued to resist marginalization. In what became known as the Berber Spring in 1980, young Kabyle men and women took to the streets following the cancellation of a lecture by the celebrated writer Mouloud Mammeri on ancient Kabyle poetry in Tizi Ouzou. The demonstrations were violently suppressed, but they inspired a series of general strikes across the region. Two decades later, in what became known as the Black Spring of 2001-2003, Kabyles responded to ongoing socioeconomic oppression, and the military’s killings of local residents and activists, by re-occupying the streets and demanding greater equality and social justice. As a child, Idir witnessed the atrocities of the French colonial order and the horrors of the Algerian revolutionary war (1954-1962). The post-independence military regime of the National Liberation Front (FLN), however, marked him even more profoundly and helped shape both his persona and his engagement with politics. Idir’s songs provided the musical amplification of this decades-long fight for the protection of Kabyle rights and the recognition of Tamazight as a national and official language, not only in Algeria but also across North Africa and the diaspora.

The Protest Singer

Like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, Idir knew that the artist must sometimes be politically engaged and use his/her artistic talent to fight against all types of oppression and injustice. By using lyrics and music to convey the pain and suffering of his people, Idir became more than a singer; he articulated the conscience of his people. Idir, along with other Kabyle singers, such as Ferhat Imazighen Imoula, Lounès Matoub, Abdelkader Meksa, and Lounis Aït Menguellet, engaged in protracted political combat, not just for identity and language but also for social justice and economic equity, earning them the title of “les maquisards de la chanson” (the freedom fighters of song), by the celebrated Algerian francophone writer, Kateb Yacine. These singers animated a burgeoning set of Berber cultural associations, which mushroomed both in Algeria and abroad in the wake of the Berber Spring. Most notably, the Berber Cultural Movement (Mouvement Culturel Berbère, or MCB), has been especially active through its various branches. The branch situated within the large Kabyle diaspora in Paris, where Idir lived most of his adult life, is active in organizing conferences on Berber culture, music concerts, exhibits, and evening courses to teach younger generations Tamazight and their ancestral region’s history. Idir played an important role in unifying the movement, knowing how to navigate its various fractures which were to emerge in the 1990s along the lines of the two major Kabyle political parties: Aït-Ahmed’s Socialist Forces Front (FFS) and Saïd Sadi’s Rally for Culture and Democracy (RCD). Idir understood very well that political fracture only helps the oppressor. As he explained to the South African singer Johnny Clegg in a televised exchange, “a song is worth more than a thousand speeches.”

In 1980, Algeria experienced a huge cultural revival, what is known as Berber Spring (Tafsut Imazighen), which was a turning point in the historiography of Amazigh people even though the struggle for Amazigh identity started within the national movement in the 1940s. This struggle in North Africa has been reinforced by the creation of the Berber Academy of Exchange and Cultural Research (1966) and the Moroccan Organization for Research and Cultural Exchanges (1967). The 1980 Berber Spring has led to the creation of the Berber Cultural Movement, the Rally for Culture and Democracy in Algeria, and the World Amazigh Congress. The Amazigh cultural movement has gained political influence in North Africa, particularly in Algeria, Morocco, and Libya, while it is improving in Tunisia.

Sadly, on May 2, 2020, the world mourned the loss of Idir, as he passed away at the age of 70. However, his music lives on, serving as a testament to his enduring legacy and the indomitable spirit of Kabyle culture. In this volume, we strive to delve into the profound impact of Idir’s music on the Kabyle community, its role in the preservation of cultural heritage, and its wider implications for the global understanding and appreciation of Kabyle identity.

In addition to scholarly examinations, this journal volume presents personal anecdotes and interviews with those who had the privilege of knowing and collaborating with Idir. Their firsthand accounts provide unique glimpses into the man behind the music, revealing the gentle spirit, unwavering dedication, and untold stories that shaped his artistic journey.

As we commemorate Idir’s musical odyssey, we extend our deepest gratitude to the late maestro who gifted us with melodies that transcend time and borders. May this collection of essays and testimonies serve as a testament to the immeasurable impact of his art, ensuring that his voice forever resonates in the hearts and minds of generations to come.

Finally, we would like to thank all those who contributed to this volume: the authors, Lounis Aït Menguellet for honoring us with the interview, Hayat, Salah and Djaffar Aït Menguellet for sending us the photos included in this volume. We also thank Kayla Garcia and Joseph Ohmann-Krause for translating into English some of the songs in this volume. The editors of Tamazgha Studies Journal (Brahim El Guabli, Aomar Boum, and Katarzyna Pieprzak) also deserve big thanks for their excellent editing contribution to this volume and for their unwavering patience while we were working on this project.

Footnotes:

[1] A type of frame drum.

[2] Achewiq is a deeply rooted Kabyle and Amazigh musical genre, characterized by its captivating poetic lyrics and melodic tunes performed (with or without instruments) by Kabyle (Amazigh) women during socio-cultural and religious events. Achewiq addresses various themes including love, marriage feast, exile, misfortune, poverty, rituals, suffering, and privations. Achewiq genre is still cherished by Amazigh people. The iconic Kabyle writer, Taos Amrouche (1913-1976), played a vital role in preserving, promoting, and revitalizing Achewiq genre.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 2 • Issue 1 • Spring 2024

Pages 3-7

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Oregon State University

University of Oran 2/Centre d’Études Maghrébines en Algérie