Preface

A Musical Tamazgha: Idir’s Contributions to Amazighity

AUTHOR: Aomar Boum, Brahim El Guabli, Katarzyna Pieprzak

A Musical Tamazgha: Idir’s Contributions to Amazighity

Aomar Boum—University of California, Los Angeles

Brahim El Guabli— Williams College

Katarzyna Pieprzak— Williams College

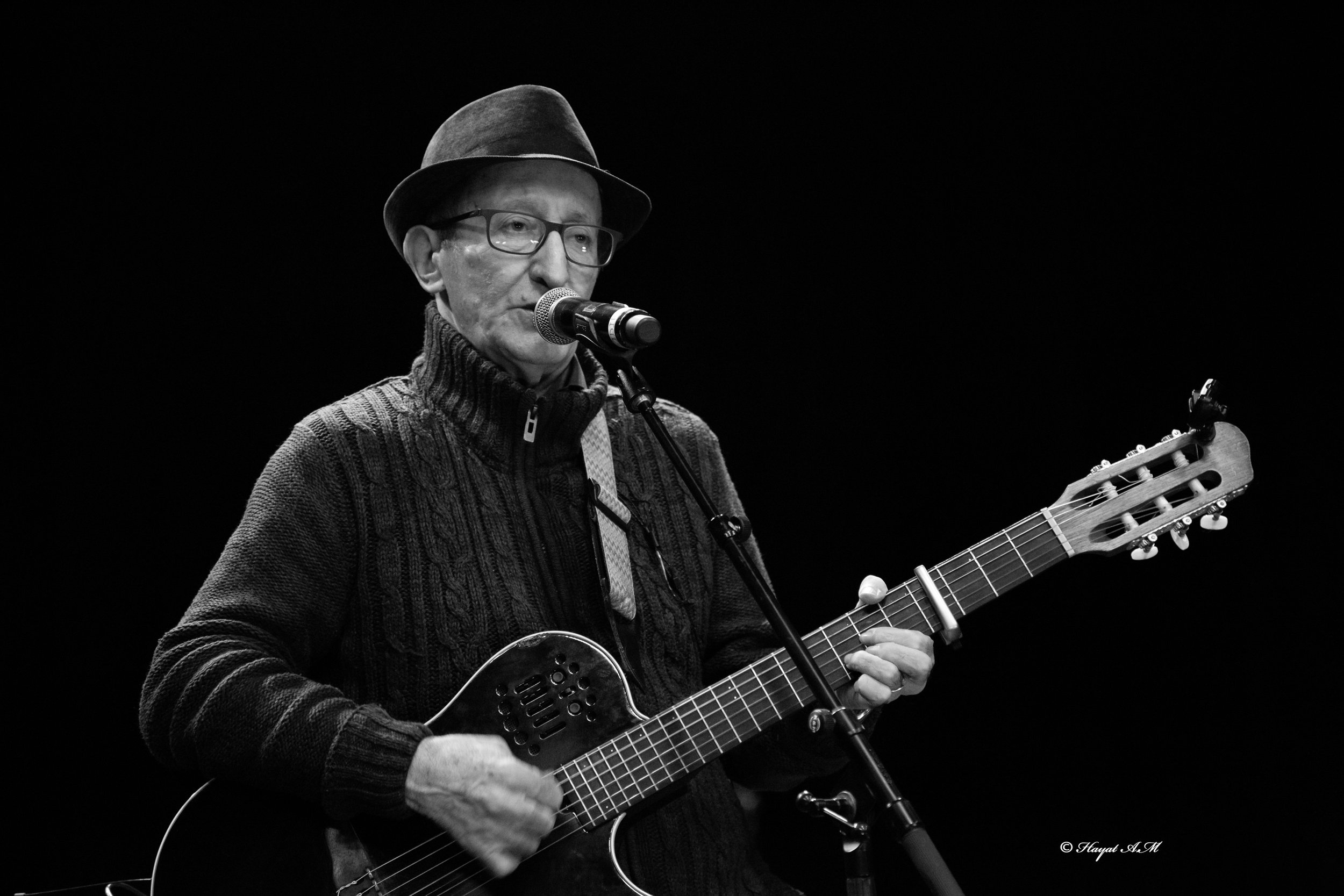

Curated by Nabil Boudraa and Karim Ouaras, this second issue of Tamazgha Studies Journal (TSJ) is dedicated to the life and legacy of one of Tamazgha’s legendary artists. In 1973, Hamid Cheriet, known by his stage name Idir, received a last-minute invitation to perform a Kabyle lullaby, “A Vava Inou Va,” on Algerian state radio after the singer who was supposed to sing that night was unable to make it to the station. This song unexpectedly launched Idir’s career as an icon of Amazigh and Tamazghan identity. “A Vava” has since been imbued with a profound cultural significance that transcends the borders of Tamazghan states and the local varieties of Tamazight. Idir’s most known song foiled the post-independence pan-Arab North African cultural and political efforts to curtail Amazigh identities by awakening the dormant yet deeply rooted expressions of Amazighity in the Amazigh homeland, stretching from the Canary Islands to Siwa, encompassing Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and other regions in sub-Saharan Africa. Although Idir was only a singer, his most popular song became a symbol of Amazigh revival and endowed Imazighen, both in the homeland and in the diaspora, with the feeling of unity they had been prevented from achieving by their self-identifying Arab-Islamic states after independence.

TSJ’s celebration of Idir’s musical legacy is not just a move to express our appreciation of the happiness that his music brought to countless Tamazghan households. Beyond this recognition, TSJ celebrates Idir’s heritage for the significance it has for understanding the local, national, and global dynamics of Amazigh culture. Culture is not to be divorced from the vital work of revitalization that fifty years of repression of Amazigh language and identity have made crucial for Imazighen to maintain their roots and existence in their homeland of Tamazgha. Cultural production has always been important for Amazigh communities, which have expressed their joys, achievements, and struggles through poetic language. Music and poetry are the heart of the construction of Amazigh sociality, allowing stronger and long-lasting ties within the community. Kabyle women, in their small agricultural plots, sang and continue to sing about motherhood, customs, weddings, and even changing seasons. During the summer, men recounted ancestral stories as they harvested their fields while their children learned these stories by osmosis. This is the environment in which Idir was first raised before he left his village and encountered a reality where Amazigh indigeneity is often shunned, ridiculed, and marginalized.

Idir’s story is the typical story of Amazigh individuals who discover their fragile existence in societies and states that give no weight to their identity. Idir’s music participated in solidifying the ties, unifying the voices, and providing an example of what is possible for Imazighen if they were to reclaim their language and culture from statal marginalization and institutional disregard. Today, Imazighen are not only still producing music but they have also expanded their creation into the novel, short story, and cinema. Now, it can be said without exaggeration that literature written in Tamazight is the fastest growing literature in Tamazgha.

The focus on Idir’s poetic legacy should not blind us to the many uses that can be made of his pioneering work. His is a living example of the various ways in which music can work as an archive of soundscapes, encounters, collaborations, and transnational solidarities between different artists from Tamazgha. Armed with unbounded curiosity and Idir’s music, one can produce significant knowledge by examining how his music was produced, the circuits in which it was distributed, and the different agents that he worked with in this process. Similarly, his music is a testament to the importance of this art as a tool for cultural and linguistic preservation in contexts in which Indigenous people are downtrodden and their heritage is denigrated. Finally, Idir’s musical legacy and sound archives tell a story of indigenous resilience and survival against the odds of intentional marginalization. His has become a voice that played a major role in imprinting Tamazgha in the consciousness of his Amazigh and global audiences.

Compiled by Nabil Boudraa and Karim Ouaras, the collection of essays in this special issue presents Idir as a multifaceted artist whose life and artistic work touched many lives and left an imprint on many people. Each of the contributors sheds light on an aspect of Idir’s life and musical legacy, contributing to our knowledge about Idir as a person and a singer. Whether they knew Idir in person or not, all the contributors pay homage to him and partake in celebrating him. In addition to the essays, the issue contains three peer-reviewed articles that address the question of music and literature in the 1970s. Lyna Ami Ali examines the connections between storytelling, weaving, and Idir’s “A Vava,” offering a fresh reading that examines the ties between cultural practices, popular literary producton, and music. Similarly, Ben Jones delves into the emergence of the musical genre of tazenart in Morocco in the 1970s. Deploying cutting-edge theoretical and historiographical scholarship, Jones sheds a new light on this musical genre and its ties to the city. Finally, Brahim El Guabli’s article reveals the articulation of Amazigh indigeneity in music even before it became explicitly expressed in the literature of the Moroccan Amazigh Cultural Movement. Combining historical research with close reading of the music, El Guabli demonstrates how singers of the tazenzart musical genre grappled with “internal colonialism” in their homeland.

Faithful to its approach to serve as a nexus for dialogues between Tamazghans and their cultural and scholarly allies, the issue features two important interviews. One with Lounis Aït Menguellet about his decades-long friendship and collaboration with Idir and the other one with novelist Mohamed Nedali who explains his recent shift to write in Tamazight after building an impressive literary career in French. The issue also features several important translations of Amazigh poetry, including Laura Sheahen’s translation of three poems by Jean Amrouche and Zahra Benlahoussine’s translation of several of Khadija Ikan’s poems. Finally, Hamid Ouyachi has contributed some of his poems in both Tamazight and English, allowing us to appreciate the poet’s poetic bilingualism in the two languages.

As we plan for the publication of the third issue in Fall 2024, TSJ invites its readers to consider themselves part of a larger project that questions the current practices of knowledge production and that aims to recenter Tamazgha in the curricular and programmatic offerings in Anglophone academia. Tamazgha has certainly changed, but academic approaches have yet to follow suit to stay abreast of the transformative achievements Tamazghan, and particularly Amazigh, cultural output has attained in the last two decades.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 2 • Issue 1 • Spring 2024

Pages: 1-2

Language: English

INSTITUTION

University of California, Los Angeles

Williams College

Williams College