Essays

Idir in the Amazigh Hinterlands

AUTHOR: Paul A. Silverstein

Idir in the Amazigh Hinterlands

Paul A. Silverstein

Reed College

Abstract: The paper analyzes how Idir’s music with its various collaborations globalized the Amazigh struggle, bringing Kabylia into direct dialogue with a host of endangered indigenous lifeworlds surviving in the hinterlands of urban and diasporic settings. A Vava Inou va anticipated and at least partly inspired the 1980 Berber Spring (Tafsut) protests, provoked by the canceling of a lecture by Mouloud Mammeri on Kabyle poetry. This paper explores how Idir’s music, and especially his later collaorations, left an indelible legacy for the Amazigh cultural movement and the anti-racist struggle for rights and recognition among people of color, of postcolonial immigrant background, and from minoritized ethno-linguistic groups in France and beyond.

Keywords: Amazigh music, activism, postcoloniality, Algeria, Morocco, France.

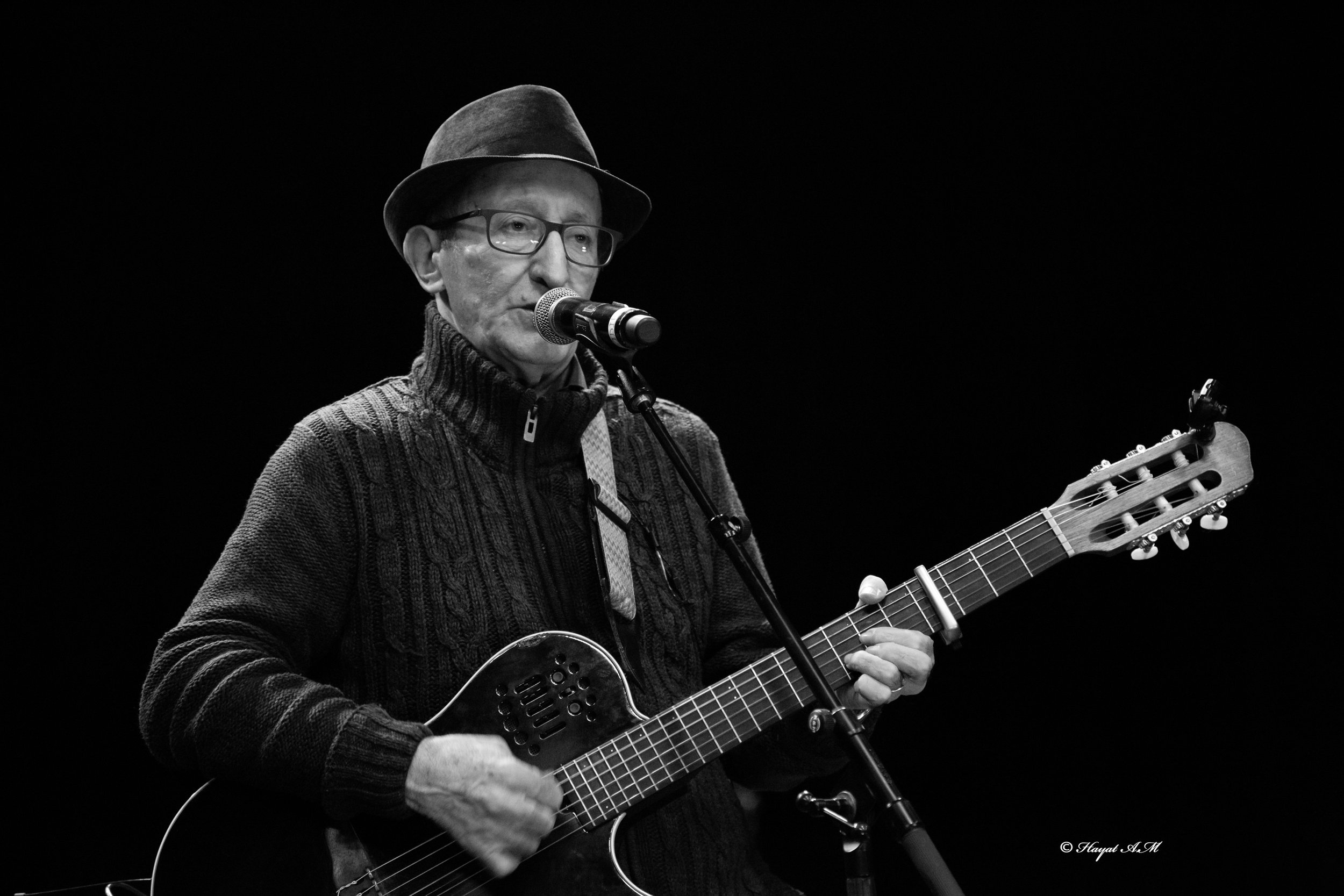

Few public figures have managed to work across as many terrains of national, cultural, and musical difference as Idir (Hamid Cheriet), who sadly departed this world on May 2, 2020. He left an indelible legacy for the Amazigh cultural movement in particular, but also for the anti-racist struggle for rights and recognition among people of color, of postcolonial immigrant background, and from minoritized ethno-linguistic groups in France and beyond. His various collaborations across genres of raï, rock, gnawa, chanson, and various folksong repertoires effectively globalized the Amazigh struggle, bringing Kabylia into direct dialogue with a host of endangered indigenous lifeworlds surviving in the hinterlands of urban metropolises and diasporic settings. This was an important intervention into “world music” which transformed the genre’s commensuration and commodification of musical traditions into an instrument for transformative politics.

Idir's oeuvre, including his first hit A Vava Inou va (O Father, My Father) from 1973, drew on the rich mythological imagery and active vibrancy of Kabyle village life and spoke out directly against the Algerian modernist aspirations for development and the Arabization policies of the decade, which treated Amazigh rural life as but an anachronistic survival. Built on a folk rock protest tradition and inspired by the new Negritude works of cultural authentication that Idir and Ben Mohamed witnessed at the 1969 Pan-African Festival in Algiers (Goodman, 2005:49-68), the song at least partially inspired the 1980 Berber Spring (Tafsut) and became the anthem of the transnational Amazigh movement. Every activist around the world knows its lyrics by heart, most can strum its basic melody, and it is surely the most common number performed at Berber concerts, rallies, and cultural festivals. Singing A Vava Inou Va launched a number of activist gatherings and Amazigh public events I attended in France during the 1990s. During one Tafsut commemoration in Seine-Saint-Denis, the public address system unexpectedly broke down, and, to keep the gathering focused, the organizers orchestrated an impromptu, collective a cappella rendition of the song. In a certain sense, the unamplified voices replaced the phatic labor of the failed technological infrastructure for the cultivation of social solidarity and cultural/political pedagogy (Elyachar 2010). Such pedagogical affordances recapitulate the song’s internal didactic theme: the transmission of local knowledge from father to daughter. Indeed, the song played a significant role in the teaching of the Kabyle language (Taqbaylit) at the Association de Culture Berbère in Paris—an important center for the Kabyle community in France and a key player in the Amazigh revival since the early 1980s—where my instructor taught heritage language learners Taqbaylit through the parsing of the grammar and vocabulary of A Vava Inou va and other sung poetry. Idir’s composition thus came to connect singers, listeners, and learners to an endangered cultural world which, because of emigration and urbanization, many younger Kabyles have never experienced first-hand.

In the intervening 40 years, Idir continued to make music from his base in Paris, mixing a village-based repertoire with work across varied cultural backgrounds and musical genres, collaborating with rock métis stars like Zebda and Manu Chao, rappers like Akhenaton, Breton folksingers Alan Stivell and Dan Ar Braz, and even chanson icons like Maxime Le Forestier, among others—all in the cause of celebrating the diversity of late twentieth-century France. In this sense, Idir's oeuvre engages a decidedly global discourse while remaining deeply Kabyle. A case in point is the evolution of another composition from his debut album, “Zwit Rwit” (loosely, “Move It, Shake It”), a festive, nostalgic homage to a Kabyle village marriage celebration (timeghra). The upbeat rhythm and lyrics call forth women celebrants’ joyful dancing, reinforced by the repeated titular onomatopoeia deriving from quintessentially feminine rural activities of sifting flour and churning butter, themselves thinly veiled sexual metaphors. (A video production of the song available on YouTube from 1976, featuring a long-haired, radiant Idir, is almost heartbreaking in its pastoral innocence.)

In 1987, raï superstar Cheb Khaled—who cut his own performative teeth animating wedding celebrations in Oran—adopted the melody of “Zwit Rwit” for “El Harba Wine” (Flee, But Where), sung in Algerian Darija. The song interrogated, "Where has the youth gone?/Where are the brave ones?" thus parsimoniously expressing the alienation of Algeria’s post-independence generation. It soon became one of the anthems of the countrywide October 1988 demonstrations, which forced the provisional opening of Algeria’s political system to oppositional movements including the Mouvement Culturel Berbère (MCB) and its representative political parties. Khaled later re-recorded the song in 1999 as a duet with Bollywood music star Amar, globalizing the jeremiad over social inequality and the false coin of emigration (For a brilliant analysis of the dilemmas of Algerian (particularly Kabyle) emigration, see Sayad, 2004).

Meanwhile, Idir himself remade the song as the title track of his La France des Couleurs (France of [Many] Colors) album, which was released in support of France's 2006 multiracial World Cup football team. The version features a variety of French rap, R&B, raï, and chanson stars, interspersing Idir’s original Kabyle lyrics with new verses—featuring in particular the Algerian-Canadian R&B diva Zaho—that celebrate the strength of France’s ethno-racial diversity and implore the state to live up to its promises of liberty, equality, and fraternity. The original phrase “zwit rwit” is translated as “move, move, and mix it up” (bouge, bouge et mélange), referencing the joy of both dancing and crossing cultural boundaries. The song concludes with a cameo by the French-Kabyle football star Zinedine Zidane intoning the song’s new refrain, “France of [many] colors will defend the colors of France,” anticipating his on-field heroics wearing the national jersey, but also perhaps his head-butt (coup de boule) defense of his family’s reputation during the final match. Notoriously soft-spoken, Zidane had earlier received criticism for not using his public stature to defend his native Amazigh culture. After the World Cup, Zidane did visit his father’s natal village in Kabylia, and many even came to celebrate the coup de boule as a positive sign of his enduring Kabyle sense of honor (nif) (Silverstein 2018:108-111).

La France des Couleurs also included a number of compositions, often sung as duets, that remade, referenced, or reframed Idir’s oeuvre. In “Retour” (Return), Idir echoes Khaled’s question from “El Harba Wine”—“O children of the emigration, where are you?” (Ay arraw n teghriben anda tellam?)—to which the French-Kabyle hardcore rapper Sinik (Thomas Gerard Idir) answers with a poignant description of growing up under France’s cold racism and false promises, drawing on his own youth in the suburban housing projects of Paris: “Child of an immigrant/At the end of his rope/I am in pain/So far from the mountains and the plains.” As with Idir’s own exile (lghorba), a longed for “return” to the homeland (tamurt) remains seemingly forever deferred.

If “Retour” gestures to earlier versions of “Zwit Rwit,” several other compositions on La France des Couleurs call forth A Vava Inou va. In “Lettre à ma fille” (Letter to My Daughter), a text written by the spoken-word poet Grand Corps Malade (Fabien Marsaud), Idir dictates a letter in Algerian-accented French to his French-born daughter Tanina about his hopes and regrets as an immigrant father, trying to put in writing what otherwise could not be expressed: “You know, my daughter, back at home (chez nous), there are things that cannot be said.” The intimate oral dialogue between father and daughter in the original mythic tale comes off as all but foreclosed by the cultural rift opened up by the time-space of exile and graphic genre of a letter. This affective scene of failed intimacy is inverted in two subsequent duets on the album—“Ya Babba” (O Father) with French-Moroccan R&B singer Wallen (Nawell Azouz), and “A Mon Père” (To My Father) with French-Algerian chanteuse Nâdiya (Nadia Zighem)—both of which even more closely rewrite A Vava Inou va, though with the vocative agency shifted all the more to the daughter. Indeed, Nâdiya literally appropriates the refrain from “Lettre à ma fille” and transforms it into, “You know papa (‘ba), there are some things between a daughter and her father which we cannot say back at home.” She addresses her father as a “citizen of the world” who taught her to respect others, who, though living “far from his land” (loin de sa terre) has remained a “free man” (homme libre).

“Free man” is the common translation of “Amazigh,” the ethnonym developed by Kabyle expatriate militants in France in the late 1960s to replace the derogatory “Berber” that had been adopted by Arab and French settler colonists from the Greek barbaros, meaning “barbarian.” The neologism was actually a source of some tension in activist circles during the 1990s, as the ongoing conflict in Algeria had driven a rift between factions within the MCB affiliated with the more nationalist-secularist Rally for Culture and Democracy (RCD) and the more transnationally-oriented Socialist Forces Front (FFS). Part of Idir’s genius was his ecumenical capacity to transcend such sectarian divides. The first time I saw him perform, in 1995 at the Zénith in Paris, he was singing a duet with the militant and polarizing musician Lounès Matoub, who had recently been liberated from Islamist captivity. Idir managed to seamlessly blend his folk guitar with Matoub’s chaabi oud playing and his lyrical pastoralism with Matoub’s strident politics. The hug that concluded the performance was one of genuine affection, respect, and solidarity in the broader Amazigh cause.

Idir and Matoub’s parallel influence was likewise evident in the southeastern oasis hinterlands of Morocco where I continued my ethnographic research in the early 2000s. Matoub’s recent assassination and the Kabyle uprisings that followed in 1998 and 2001 clearly marked the area, with graffiti around the village honoring Matoub’s rebellious legacy and activists finding local truth in the refrain of “Pouvoir assassin” (a reference to the Algerian military, but perhaps also to the Moroccan makhzen), recently popularized in a song of that name by the Kabyle singer Oulahlou. But it was Idir’s melodies that defined the oasis soundscape. One local artist and activist, Chuchu, had taught himself Idir’s repertoire on a second-hand guitar and led us in festive renditions of “Zwit Rwit” when we retreated to the local hills, fruit gardens, or springs to escape the late-afternoon heat. While he styled himself on the Kabyle bard, at some point he transferred that identification, dubbing me “Yidir” for my interest in Kabyle politics and tendency to disappear from the oasis for years at a time, only to be “born again” upon my return. I carried back some of Chuchu’s intuitions about the inter-animation of music and politics to the United States, where they have been occasionally re-animated by Kabyle friends and their own writing and musical projects. Idir may have passed, but, like his name, he lives on in the hearts and dreams of Amazigh activists and their allies across the globe, maybe even in the hinterlands of Oregon.

References

Elyachar, Julia. 2010 “Phatic Labor, Infrastructure, and the Question of Empowerment in Cairo.” American Ethnologist 27(3): .

Goodman, Jane E. 2005. Berber Culture on the World Stage. Bloomington: Indiana University Press,

Sayad, Abdelmalek. The Suffering of the Immigrant. Cambridge: Polity, 2004.

Silverstein, Paul A. Postcolonial France: Race, Islam and the Future of the Republic. London: Pluto, 2018.

How to Cite:

Silverstein, P. A., (2024) “‘Between Boston and At Yenni: Two Musical-Cultural Journeys”, Tamazgha Studies Journal 2(1), 62-65.

DOWNLOAD

ISSUE

Volume 2 • Issue 1 • Spring 2024

Pages 62-65

Language: English

INSTITUTION

Reed College

Keywords: Amazigh music, activism, postcoloniality, Algeria, Morocco, France.